You’re running down a plant-lined path, lost on a strange planetoid, when you find a logbook. It belongs to a human-like being named Dirca. The book explains Dirca’s discovery of a strange substance, which she believes came from another world made up of antimatter.

The world you discover in the video game Exographer is imaginary, but to survive, you must learn lessons based on real physics.

That’s because the idea for the game came from Raphael Granier De Cassagnac, a French physicist who works on the PHENIX experiment, hosted at the US Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory, and the CMS experiment, hosted at European physics laboratory CERN.

Science and science fiction

Before he was interested in physics, Granier De Cassagnac was interested in science fiction and fantasy. He grew up reading Dune and The Lord of the Rings.

He was also an early gamer. In middle school, he discovered tabletop role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons and Call of Cthulhu. In his teens, he played Boulder Dash, Gauntlet, and Ghostbusters on his family’s Amstrad 8-bit home computer.

His enthusiasm for physics blossomed in high school, when he learned that experiments at the Large Electron-Positron Collider—a precursor to the Large Hadron Collider—were able to precisely study the interactions of fundamental particles, even though some of those particles were invisible to the scientists’ detectors. “I was just like wow, I was totally fascinated,” he says.

In college, he pursued a PhD in physics, focusing on antimatter, then went on to do research on the PHENIX experiment, focusing on studies of an extreme state of matter called the quark-gluon plasma.

But he didn’t forget his passion for speculative fiction. He wrote before work, on holidays and weekends, and on trips between France and New York.

From 1999 to 2002 he designed several tabletop role-playing games. Then in 2011, he published his debut science-fiction novel, Eternity Incorporated. In 2014, he published a sequel, Thinking Eternity, which won a French-language science-fiction award, the Prix du Lundi.

Granier De Cassagnac says his role-playing games and novels steer clear of physics, but his books do illustrate some aspects of the life of a scientist. “The way we do science, the way we produce knowledge, these are the things I wanted to talk about in my books,” he says.

Turning science into play

Granier De Cassagnac had been commuting between Europe and the United States to study the quark-gluon plasma. But once the LHC started up at CERN, he had the opportunity to study the same thing right in France. The LHC spends a small portion of its time colliding heavy ions, a process that produces the QGP.

Granier De Cassagnac applied for a grant to join CMS’s heavy-ion program, which was at the time not yet funded in France. At the end of the grant, he had access to an extra call to bring to market the results of his research.

Because he was conducting basic research and not developing a product, he decided to use the call to pitch a video game. His initial proposal was rejected, but with encouragement from his coworkers, he kept trying until he found the funding he needed.

In the beginning, Granier De Cassagnac knew nothing about making video games. But as a researcher in scientific collaborations with members numbering in the hundreds (in the case of PHENIX) and thousands (in the case of CMS), he knew how to lean on the expertise of others.

Granier De Cassagnac interviewed game developer Pierre-Alban Ferrer, asking him to imagine a concept based on science. Ferrer had no science background, but he proposed a game in which the player needed to use the gravity of a planet to play minigolf. He got the job.

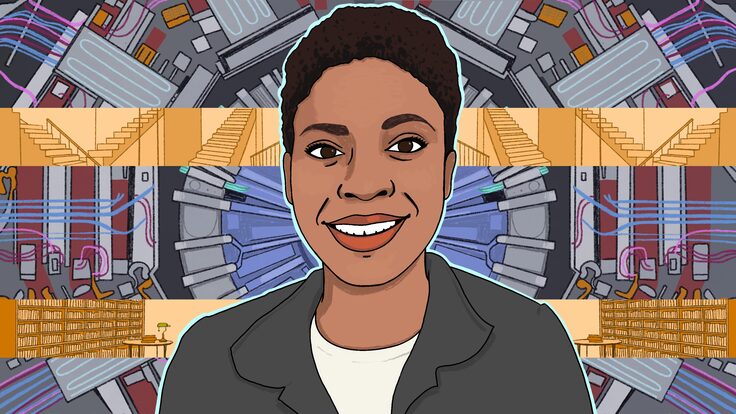

Granier De Cassagnac then rounded out the team with members Catherine Rolland (producer), Thomas Vaulbert (graphics artist) and Tony Cottrel (game developer). The game they created will be released for PCs and consoles in fall and is available on online gaming platform Steam.

In Exographer, you overcome challenges to move from place to place in an environment. In the process, you uncover testimony from a lost civilization. You work to repair the experiments that civilization left behind—and gain the powers associated with their science. For example, when you fix an experiment related to the gluon—the particle associated with the force that binds quarks together in protons and neutrons—you get boots that can stick on the ceiling.

Rolland, who in addition to 15 years’ experience making video games has a doctorate in chemistry, shared Granier De Cassagnac’s interest in making a game that would let people play with complex science. “The goal is to deliver a game that people who think they have nothing to do with science can enjoy,” she says.

For those who are in the know, the team hid multiple science-related Easter eggs. Aliens are named after real scientists—Dirca, for example, is a nod to physicist Paul Dirac. Places are based on real labs. The experimental set-ups include real Feynman diagrams, representations that scientists use to communicate the steps in a particle interaction.

But the game is accessible to players without a background in physics as well. “If people play the game and have fun, I’ll be happy,” Granier De Cassagnac says.

Those players may even learn a thing or two. During an early test of the game, several non-physicist testers gained enough experience with Feynman diagrams to notice a bug: An arrow in one was pointed the wrong direction.

Granier De Cassagnac says he hopes players like that continue to explore the science. “I would be super happy if some of the players got beyond the game and became interested in physics.”