It was her 31st birthday, and Jordan Glover was in a rut. She was a college drop-out with a decade of retail and customer service jobs under her belt, living paycheck-to-paycheck as a stocker at Costco.

“I didn’t have enough money to pay my bills,” she says. “I was in this cycle of always trying to find a job that pays enough, but I don’t have any qualifications, my skillset was a general skillset. I was very financially unstable and tired of being in that situation.”

Glover had always been bright and ambitious. For her 4th grade science fair, she spent several mornings hiking to nearby houses with a blood pressure cuff to measure the effects of coffee on adults’ vital signs. “I got positive results,” she says.

Both of Glover’s parents work in the medical field, and she assumed she would similarly wind up in STEM. She enrolled in Tougaloo College—a historically Black college in Jackson, Mississippi—to study chemistry, but something didn’t click. Suddenly, “I just wasn’t motivated,” she says.

At the age of 19, Glover dropped out in search of a different path.

Now in her 30s, Glover found herself again feeling lost—until her sister gave her a pep talk. “My sister told me, ‘I think you’re afraid to be successful; you keep thinking that you’ll fail, but the only way you fail is if you fail to try. So why not try and give it your all?’ It was like a lightbulb went off, and I became that person,” Glover says. “I wanted to take advantage of every opportunity.”

Glover knew that she wanted to go back to school, but she didn’t know how to go about it. Then, one day at work, she saw her former Tougaloo physics professor. “I took that as a sign,” she says.

She decided to re-enroll, this time as a physics major. Her timing was impeccable, because that same year Tougaloo College partnered with the US CMS collaboration as part of PURSUE, a program designed to bring opportunities to students just like Glover.

Creating opportunities

Glover was intelligent, diligent and open to new challenges. Thanks to her experience working in many different roles with many different types of people, she had developed a unique perspective and a variety of skills—all valuable assets for working with a team doing scientific research.

“Hobbies and past work experience are non-trivial,” says Javier Duarte, a professor at the University of California, San Diego who helped develop the recruiting rubric for PURSUE, the Program for Undergraduate Research Summer Experience. “They give students skills like teamwork, good communication, awareness and the ability to navigate complex work environments.”

But despite being well suited for science, Glover was also the kind of student traditional STEM recruitment methods tend to miss.

Duarte knows how hard it can be to break into research. He and his family immigrated to the United States in 1990, when he was 2 years old. His mom was an entrepreneur who instilled in him the value of scholarship, but she wasn’t familiar with the US higher education system, Duarte says.

Luckily, Duarte fell in with a group of local friends who were in-the-know when it came to college prep and applications. When Duarte applied to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology during his senior year of high school, he was accepted.

At MIT, opportunities to do research abounded. “It’s MIT, and it’s what everyone does,” he says. “My friends were applying for research, and so that’s what I did too. I did my first [research experience for undergraduates] freshman year.”

Starting early in research makes students strong candidates for future opportunities, says Tulika Bose, a professor at the University of Wisconsin and one of the co-coordinators of PURSUE. The availability of research opportunities makes a student from a research university stand out, even when the prestige of their institution is purposefully not taken into account.

The first year the US contingent of the CMS experiment offered their internship program, they removed applicants’ universities from consideration during the selection process, Bose says. But “when we looked at who we had selected, the top 20 students all came from top universities.”

More and more, physicists are realizing that, if they want to increase diversity in in STEM, they need to actively recruit students from underrepresented populations, including those at minority serving institutions.

Right place, right time

At first Glover tried to juggle work and her return to school, but she quickly realized it was unsustainable. “I had Cs and was on my way to an F,” she says.

So she quit her job at Costco, moved into the dorms, and became a full-time student.

“In the past, I would always quit school and keep my job,” she says. “This time, I had to adapt to the broke-college-student mindset. Giving up my two-bedroom, two-bathroom apartment and quitting my job so that I could go to study sessions were the hardest things I’ve ever had to do in my life.”

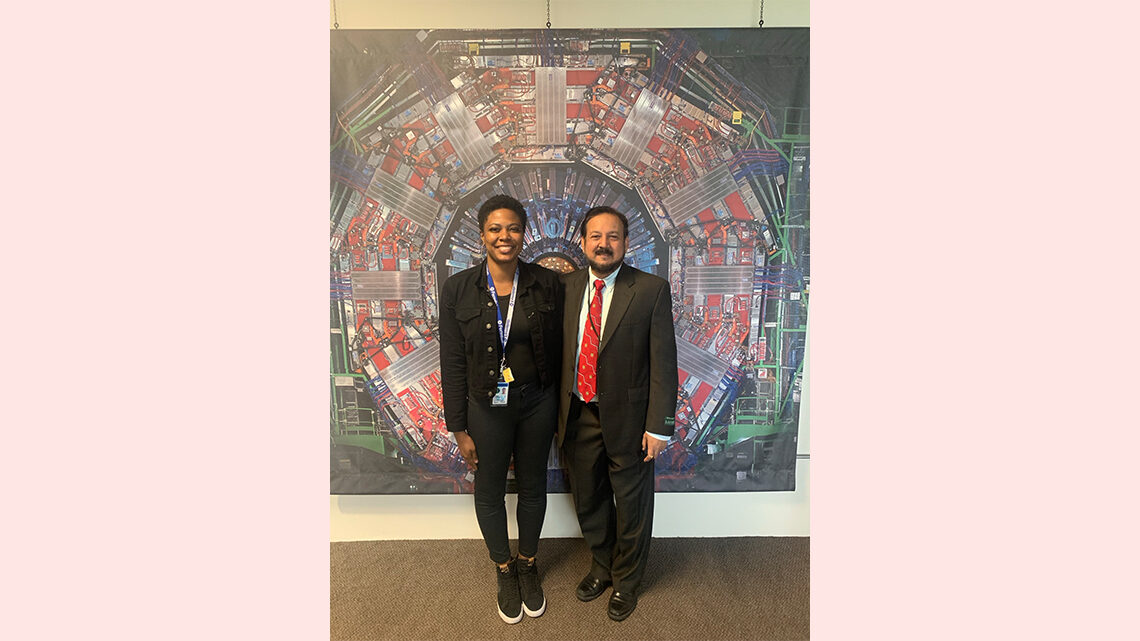

Her dedication paid off. Her grades improved—she got all As and one B—and in the spring of Glover’s sophomore year Tougaloo physics professor Santanu Banerjee encouraged her to apply for PURSUE.

On the program’s application webpage, Glover got her first glimpse of a photo of the Large Hadron Collider, the gigantic accelerator that provides particle collisions for the CMS experiment to study. “I was like, what is this?” she says. “I needed to know more.”

Glover was accepted to the program. Over the summer she spent two weeks at the US Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Illinois with 20 other interns to learn about coding and the ins-and-outs of particle-physics research. She then spent eight weeks at Purdue University in Indiana to use CMS data to study the top quark.

“For the top quark, I had to look at what they had done in the past to see where they were trying to go and how it was going to benefit the theory they were trying to improve,” she says. “I had to read so much documentation, but once I was able to get those computer programs running, I was like, Oh my goodness I did it!

“I got to collaborate with different teams, and I was diving into the history of the topic as well as taking steps towards the future.”

Glover says that she is grateful to the coordinators of PURSUE as well as the Department of Energy, which provided housing and a stipend throughout the program so she could focus on her research.

“In the past, I’ve started things but never finished them,” Glover says. “I didn’t know very much at the start of the internship, and I was completely terrified that I was going to fail. And then finishing and succeeding, I came back to school motivated and ready to tackle new things. I’m proud of myself because I finished something, and now I can see myself finishing school and not giving up.”

Glover says after earning her undergraduate degree, she plans to apply to graduate school—either in high-energy physics, biophysics or aerospace engineering—so that she can continue to do research.

“Before, I thought I wasn’t good enough,” she says, “and now I can’t wait for next summer to do another internship. It was such an amazing feeling. It gave me a boost of confidence because I know what’s on the other side of getting my degree.”