Since he was five years old, Edgar Marrufo Villalpando has known he wanted to be a scientist. But it wasn’t until middle school that he knew what kind.

Marrufo Villalpando grew up in a small town in Durango, Mexico. In his middle school science textbook, he found a sentence that read something like: Physicists are just normal people who want to understand how the universe works. That was the moment he realized physics was for him.

“Having the possibility to study the universe and the physical processes that govern the world was really attractive to me.”

Marrufo Villalpando didn’t personally know any scientists, so he did his own research on how he could become one. One of the first steps, he learned, was going to college.

Colleges in his state did not offer physics or astronomy majors, and Durango is almost 600 miles to the southeast of Mexico City, home of the internationally recognized Institute of Physics at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Marrufo Villalpando and his parents realized that he would have more opportunities if he traveled north, to where his father had recently gotten a job in the United States.

The family moved about 1,000 miles to Flagstaff, Arizona, just as Marrufo Villalpando entered high school. Starting at a new school in a new country, Marrufo Villalpando faced a particularly pressing challenge: He didn’t know English.

He was completely out of his element, but Marrufo Villalpando was determined to learn everything he needed to excel—a trait that continues to sustain him.

Today, Marrufo Villalpando is a PhD candidate at the University of Chicago with a bachelor’s degree in astronomy and physics, a DOE Office of Science Graduate Student Research Fellowship, a Graduate Instrumentation Research Award Fellowship, experience working at a US national laboratory, and an instrument that he helped to build installed on a telescope in Chile.

“He’s very meticulous,” says Juan Estrada, a scientist who worked closely with Marrufo Villalpando at the US Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. “Once he decides to learn something, he really puts in the effort to learn it in detail.”

Picking up the language

In part because his father used to travel regularly between Durango and Los Angeles to work, Marrufo Villalpando had some exposure to English as a child. But his understanding was limited to some basic words and phrases.

So, Marrufo Villalpando immersed himself: He enrolled in English-learning courses, watched YouTube videos in English and worked closely with his teachers in Arizona. His father was able to help with some tasks, like understanding instructions on homework, and his English improved along the way, too. (Meanwhile, Marrufo Villalpando excelled in math, a subject taught in the universal language of numbers.)

After six months, Marrufo Villalpando says he was fluent enough for college-level “advanced placement” classes for high schoolers. He ended up taking multiple AP courses before graduating high school—including AP English—but physics was still the subject that fascinated him the most. “Having the possibility to study the universe and the physical processes that govern the world was really attractive to me,” he says.

Marrufo Villalpando also participated in Upward Bound, a national program for low-income or first-generation college hopefuls. Upward Bound allowed students like Marrufo Villalpando to receive application assistance and get a taste of college life: Marrufo Villalpando took summer courses at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff. He was so strongly affected by the program that he chose to attend NAU for his bachelor’s degree in physics and astronomy.

Marrufo Villalpando began doing research in computational physics, a field that uses math, physics, computer programming and numerical analysis to solve scientific problems. His junior year, Marrufo Villalpando began a research project with associate teaching professor Lisa Chien, simulating the dynamics of galaxies and their dark matter halos.

When it was time to apply for graduate schools, Marrufo Villalpando sought universities with dark matter and cosmology programs. The University of Chicago—with its Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics, its connection to nearby national laboratory Fermilab, and its broad programs in particle physics and cosmology research—became his top choice. When he found out he was accepted to their PhD program, he says, “I was in disbelief.”

But Marrufo Villalpando was also determined—and ready for this next step.

A greater challenge

Marrufo Villalpando started at UChicago in 2019. “It was a challenging experience from the start,” he says.

Professors expected more from graduate students, and the difficulty of classes was higher than he had experienced as an undergrad. “It was a matter of catching up to the level of physics that I was expected to know and understand,” he says.

About 30 graduate students entered the physics department that year, and Marrufo Villalpando soon discovered that many of them felt similarly. He felt reassured “seeing that it’s not just me, I’m not the imposter here,” he says.

The cohort found camaraderie in community. Together, they worked through classes, homework and lectures; Marrufo Villalpando says some of his favorite memories from UChicago are late Sunday nights spent collaborating with his classmates.

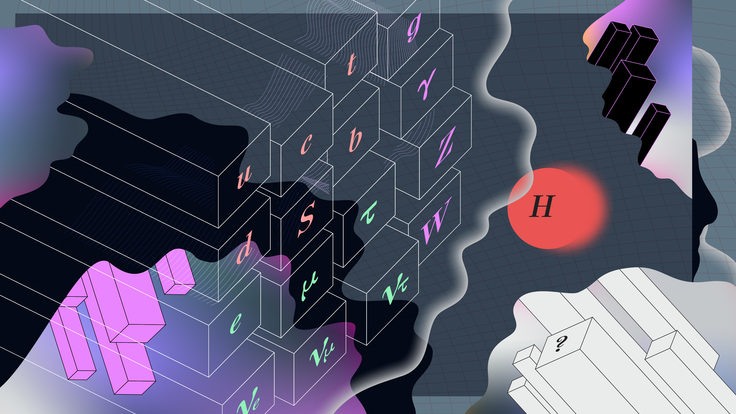

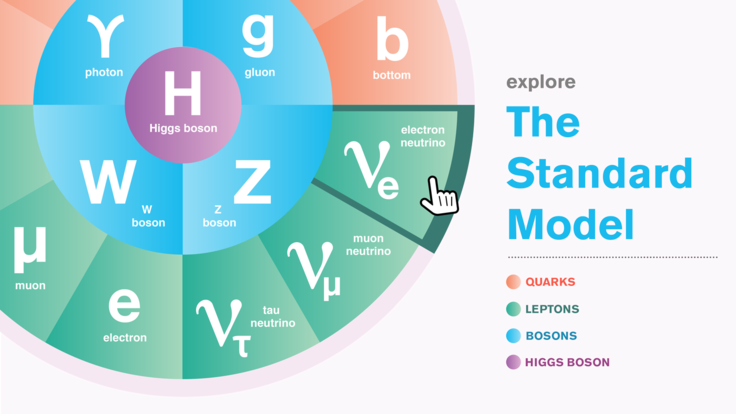

In their first semester, UChicago physics graduate students try different research projects. Marrufo Villalpando’s interest in dark matter and cosmology drew him to research by Alex Drlica-Wagner, a professor at UChicago and Fermilab scientist who wanted to optimize an older detector technology, skipper CCDs, for a new use in astrophysics. Drlica-Wagner wanted to use the technology to observe low-photon-count events, which would benefit dark matter and dark energy studies.

The idea built upon many years of work from scientists at Fermilab, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and others. But for Marrufo Villalpando, adapting this decades-old technology for cosmology was “pretty much a project from scratch,” he says. “I took the role of learning everything about it.”

Diving in

Marrufo Villalpando was tasked with characterizing and optimizing the detectors and understanding how they worked, which involved learning about electronics and developing data pipelines. Marrufo Villalpando’s previous work in computational physics had been more theoretical; he had certainly never built anything for an experiment. To transition to astrophysical instrumentation, Marrufo Villalpando would need training from experts in the field.

So Drlica-Wagner began bringing Marrufo Villalpando to Fermilab.

Marrufo Villalpando says he quickly discovered that Fermilab was rich in resources, especially people. Electrical engineers, mechanical engineers, physicists and computer scientists were just around the corner. “It was fascinating to learn and just to be immersed in that kind of collaborative environment,” he says. “I think that was the best thing about my opportunity to work here at Fermilab: to make connections and learn from everyone.”

Learning from the large number of researchers in Fermilab’s CCD group was especially beneficial for Marrufo Villalpando. Led by physicist Juan Estrada, the group has been at the forefront of skipper-CCD technology since 2017. Estrada became Marrufo Villalpando’s national lab supervisor when he earned the DOE Office of Science Graduate Student Research Fellowship.

Working in the CCD group, Marrufo Villalpando was determined to learn everything he could about the technology’s applications for studying dark matter so he could adapt it for his own project. He jokes he practically became an electrical engineer in the process.

But once he gained that knowledge, Marrufo Villalpando didn’t limit himself to his own work; he contributed to other skipper-CCD experiments at Fermilab, including SENSEI and OSCURA. “At the beginning, we were teaching him,” says Estrada. “Pretty soon, he was helping us with everything we needed and teaching us the details that we didn’t know.”

Estrada says Marrufo Villalpando’s help earned him co-authorship on several papers. “He was really collaborative with all the other scientists, engineers and younger students that came after him,” he says. “He helped a lot of people. That’s not typical for graduate students, who are often in a rush to complete their work and don’t have a lot of time… I really didn’t expect him to become such an integral part of our group and participate in everything else that we were doing.”

His assistance wasn’t limited to science. Estrada says Marrufo Villalpando would volunteer as an additional player on their recreational soccer team—and as an additional chef at their recreational cook-outs. “A lot of us in the CCD group are from Argentina,” Estrada says. “We pride ourselves on making good barbecue, but he challenged us that he could make something better with his Mexican carne asada. And I can tell you, it was pretty good!”

Looking to the sky

While Marrufo Villalpando was working on his astronomy-optimized skipper CCDs, he used them to measure the light from a calibration lamp. In 2023, he and Drlica-Wagner decided the detector was ready for a different light—the kind collected by the 4.1-meter Southern Astrophysical Research Telescope. Marrufo Villalpando traveled twice to the Cerro Tololo-Interamerican Observatory on top of Cerro Pachón in the Chilean Andes to prep and test his detector.

On the nights of March 31 and April 9, Marrufo Villalpando and his collaborators used their instrument, mounted to the giant telescope, to take spectra of a galaxy cluster, two distant quasars, and a galaxy with bright emission lines. In a first for astronomical CCD observations, they achieved sub-electron readout noise and counted individual photons at optical wavelengths.

“[The most rewarding part was] to see that our detectors were collecting light from some objects light-years away from us,” says Marrufo Villalpando. “Not just a lamp that we have in the lab, but something really cool and grandiose like a star—the photons from that traveled and landed on our detector.”

Being in Chile also brought his journey full circle: After moving to the US as a child and learning English in six months to pursue college and become a scientist, Marrufo Villalpando was speaking Spanish again—as a scientist testing a detector he designed, developed, characterized and built.

Marrufo Villalpando is on track to finish his physics PhD by the end of the year. After graduation, he plans on “exploring new areas” and is curious to seek opportunities in industry. “I am not sure what kind of area I would be going to, but I would like to find something where I can still make contributions with my research work,” he says.

“The hope [for students] is always that they become their own independent, self-driven and self-directed scientists,” says Drlica-Wagner. “And that’s definitely true of Edgar.”