Completing a PhD in physics is hard. It’s even harder when you’re one of the first to do it not just at your university, but at any university in your entire state.

That’s exactly the situation Wenzhao Wei and Dan Rederth found themselves in earlier this year, when completing their doctorates at the University of South Dakota and the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, respectively. Wei and Rederth are graduates of a joint program between the two institutions.

Wei found out just a few weeks before going in front of a committee at USD to defend her thesis. A couple of students ahead of her had dropped out of the PhD program, leaving her suddenly at the head of the pack.

“When I found out, I was very nervous,” Wei says. “When you’re the first, you don’t have any examples to follow, you don’t know how to prepare your defense, and you can’t get experience from other people who have already done it.”

She recalls running between as many professors and committee members as she could for advice. “I did a lot of checking with them and asking questions. I had no idea what they would be expecting from the first PhD student.”

Despite her wariness, and with some significant publications in the field as the first author, Dr. Wei’s defense was successful, and she is now working as a postdoc at the University of South Dakota.

Rederth knew he was the first at SDSMT but wasn’t aware it was a first in South Dakota until after he had handed in his dissertation and completed his defense. “The president of the school told me I was the first in South Dakota after I finished,” he says. “But I wasn’t aware that Wenzhao had also completed her PhD at the same time.

“Being the first, I was not prepared for the level of questioning I received during my defense – it went much deeper into physics than just my research. Together with Wenzhao, being the first in South Dakota really is a feather in the cap to something which took years of hard work to achieve.”

Different paths to physics

Rederth started on his path to physics research at a young age. “The most satisfying aspect of my PhD research dates back to my childhood,” he says. “I was always intrigued by magnetism and the mystery of how it works, so it was fascinating to do my research.”

His work involved studying strange magnetic quantum effects that arise when certain particles are confined in special materials. A computer program he developed to model the effects could help bring new technologies into electronics.

For Wei’s success, you might expect she had also always made a beeline to research, but physics was actually a late calling for her. At Central China Normal University, she had studied computer science and only switched to physics at master’s level.

“In high school, I remember liking physics, but I ended up choosing computer science,” Wei says. “Then at college, I had some friends who did physics who were part of the same clubs as me, and they kept talking about really interesting things. I found I was becoming less interested in computer science and more interested in physics, so I switched.”

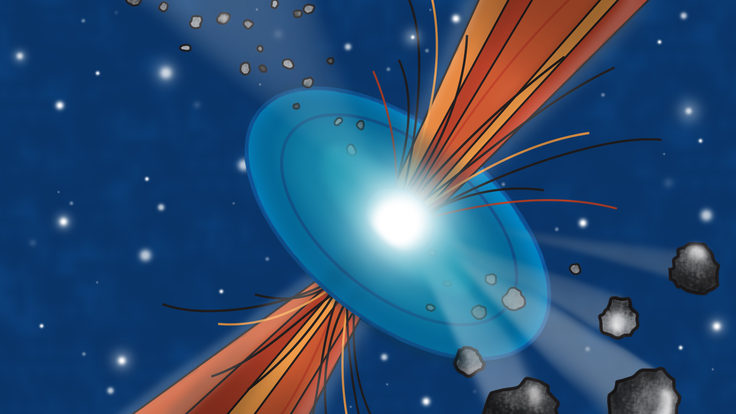

Wei’s thesis, entitled “Advanced germanium detectors for rare event physics searches,” and her current research involve developing technologies for new kinds of particle physics detectors—ones that use germanium, a metal-like element similar to tin and silicon. Such detectors could be used for future neutrino and dark matter experiments.

South Dakota is already home to a growing suite of physics experiments located a mile beneath the surface in the Sanford Underground Research Facility. It was in part a result of these experiments being located in the same state that Wei’s pioneering PhD program came about. USD has been involved with several experiments at SURF, among them the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, which will study neutrinos in a beam sent from Fermilab 1300 kilometers away.

“DUNE and SURF have been a vehicle to move the physics PhD program at USD forward,” says Dongming Mei, Wei’s doctoral advisor at USD. “With the progress of DUNE, future PhD students from USD will be exposed to thousands of world-class scientists and engineers.”

Post-doctorate, Wei is now continuing the research she began during her thesis. But with a twist.

“For my PhD, I did lots of computer simulations of dark matter interactions, so I spent a lot of time stuck at a computer,” Wei says. “Now I’m actually able to get hands-on with the germanium crystals we grow here at USD and test them for things like their electrical properties.”

So where next for South Dakota’s first locally certified doctors of physics?

“I want to stay in physics for the long-term,” Wei says. “I taught some physics to undergraduates during my PhD and really loved it, so I’m hoping to be a researcher and lecturer one day.”

Rederth, too, wants to help inspire the next generation. “I want to stay in the Black Hills area to help raise science and math proficiency in the local schools. I’ve been a judge for the local science fair and would like to become more involved,” he says.

Perhaps some of their future students will go on to join the list of South Dakota’s physics doctorates, started by their trailblazing teachers.