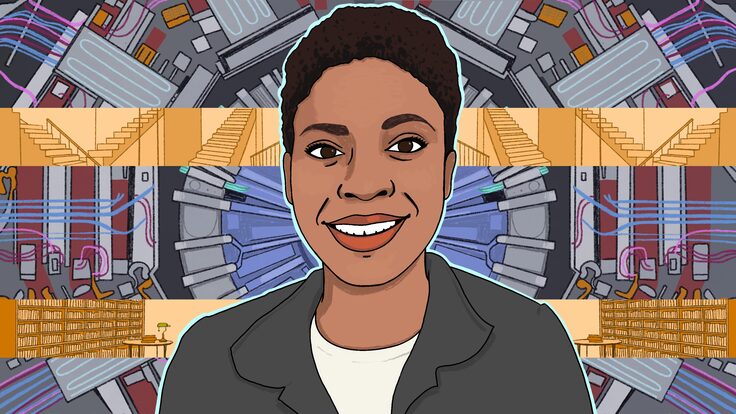

Kétévi Assamagan first became interested in physics in high school—because he had to be. His school in Togo, in West Africa, required students to declare a major. Students had three options: literature and philosophy; natural sciences; or math and physics.

“I was good at math, and I wasn’t so great at the other subjects, so I picked math and physics,” Assamagan says.

Fortunately, he never stopped being good at math, and he ended up excelling at physics.

Today, Assamagan is a physicist at the US Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory. He contributed to the 2012 discovery of the Higgs boson, among other accomplishments. But there was a time when, despite his early proficiency in the subject, he wasn’t sure he could make it as a physicist. He credits two educators with shepherding him toward the path that has led him to the career he has today.

In return, Assamagan is dedicated to helping other physicists across Africa. He does this through the African School of Fundamental Physics and Applications and through the African Strategy for Fundamental and Applied Physics, efforts that Assamagan co-founded. The school offers a 3-week intensive learning program in physics for upper-level college students from throughout the continent, and ASFAP is a grassroots effort to build a strategic plan for creating impactful physics education and research in Africa.

“Kétévi is a beacon that illuminates hope for a new world that can be,” says colleague and friend Simon Connell, a professor of physics at the University of Johannesburg in South Africa. “He has humble beginnings, with resource disparity and lesser opportunity, yet he is excellent. He has devoted himself to the dual goal of scientific excellence and science as an engine for democracy.”

Finding a way

Assamagan was born in Gabon, but when he was four, his parents moved the family back to their home country of Togo. Assamagan says they made sure he and his seven younger siblings regularly attended school and received an education, something not all Togolese people could do. “My mother didn’t know how to read and write, and neither did a lot of people,” Assamagan says.

His parents would have liked for him to become a medical doctor, but he decided to pursue a doctorate in physics instead. “I thought it was going to take too long to become a practicing medical doctor, and I wanted to get a degree and a job quickly.”

Of course, most physicists would not describe the path to a PhD as quick. “As it turns out,” he says, “it actually takes a very long time to become a physicist.”

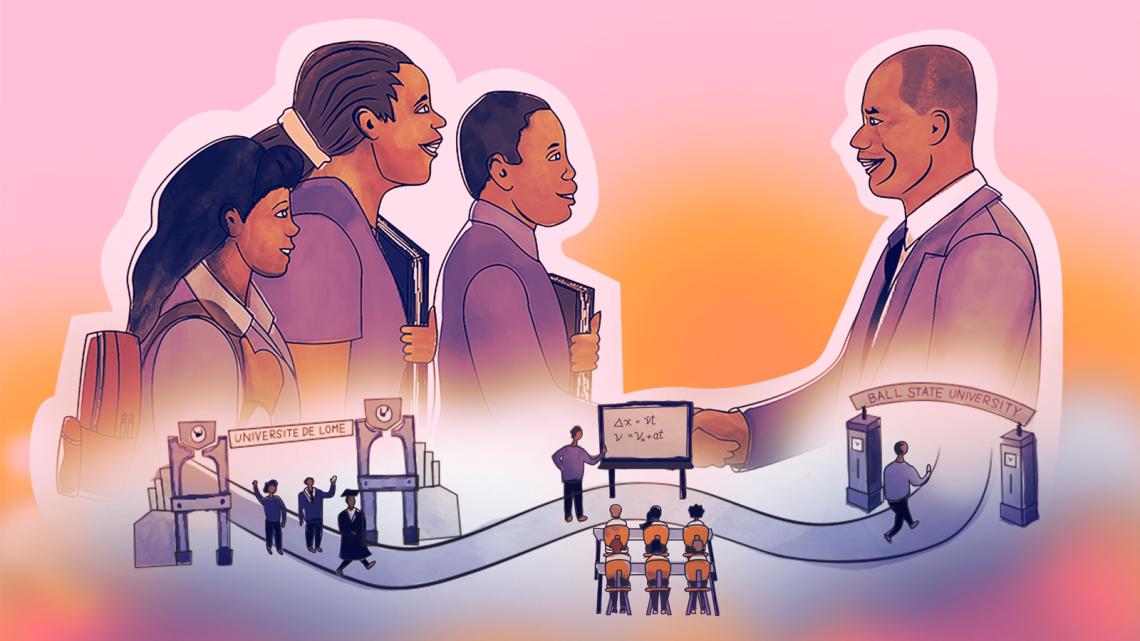

He applied to the University of Lomé, which was at the time the only public university in Togo. The competition to get in—and stay in—was incredibly tough. It often took students five years or more to earn their bachelor’s degrees. But Assamagan excelled at academics and sailed through his program in three.

Eager to continue his schooling, he applied for scholarships for graduate school. “On paper, it looked like I should have a scholarship because I had excellent grades,” he says, “but I wasn’t well connected, so it didn’t matter how well I had done.”

However, Assamagan’s outstanding academic performance hadn’t gone unnoticed. Hoping to help the star student, the head of the physics department at the University of Lomé arranged a meeting between Assamagan and a government official.

“I was really nervous,” Assamagan says. “I was 22 years old and going to speak with the Minister of Technical Education—that’s [on the level of] the Secretary of State for the entire country. He’s in this nice air-conditioned office and dressed in a nice suit. It was very intimidating.”

The minister told Assamagan about another scholarship he could apply for, one awarded by the US Agency for International Development and the Africa-America Institute. But to be eligible for the scholarship, the minister explained, Assamagan would need to have job experience.

Assamagan found a position teaching high school physics. It was “very weird,” he says, because “my colleagues were my parents' age, and the people I was teaching were almost my peers.”

After two years of teaching, Assamagan won the scholarship.

Assamagan says he will never stop being grateful for the support he received. “These two gentlemen—the head of the department and the Minister of Technical Education—were not related to me. They didn't have to help me. They did it because they believed they should do something for me, a young person who had some academic promise.”

Paying it forward

With funding from the scholarship, Assamagan attended Ball State University in Indiana, where he earned his master’s degree researching solar panel efficiency.

Graduate school was Assamagan’s first opportunity to collaborate with a university professor, and he says doing so in the United States came with some culture shock.

“In Togo at the time, and perhaps still now, the dynamic between the student and the professor is extremely formal,” he says. “But when I came to the US, I realized that I can have a much more free discussion with a professor and even disagree with them... And he or she will view it as a scientific discussion that is called for, and it's actually what people expect from prestigious students. I was quite surprised.”

After earning his master’s degree, Assamagan moved to the University of Virginia to complete his PhD, in nuclear physics. Since 1998, he has been a collaborator on the ATLAS experiment at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN.

In 2007, Assamagan met Connell at the Annual Conference of the South African Institute of Physics. At the time, Assamagan was the Physics Analysis Tools Coordinator for ATLAS. He convinced Connell’s research group that South African physicists should launch their own initiative for the LHC experiment.

“Remarkably, in a few hours, Kétévi installed and demonstrated the vast ATLAS software suite,” Connell says. “He persuaded our group that with his help, we could manage to join and make an effective contribution from South Africa to ATLAS.”

That was only the beginning of Assamagan’s effort to help further physics in Africa.

In 2008, Steve Muanza, Assamagan’s colleague at CERN, approached him with the idea to develop a new school for particle physics. “I thought it was a good idea and something we needed,” Assamagan says.

He joined the effort, along with Muanza and three other organizing committee members. In 2010, after securing funding, the group hosted their first African School of Physics.

Since 2012, Assamagan has taken the lead in ensuring the school’s continued success. “It has become extremely important to me, personally,” he says.

Under Assamagan’s leadership, the school has expanded beyond particle physics to also cover additional physics topics. Assamagan says he’s proud of the many former students that have gone on to excel in their careers, and he’s heartened that several of them have returned to teach classes.

“I think that's really the best part, because I can see the impact of what we have been doing, and also the direction that we are giving to these students,” he says.

“Kétévi really cares, and exerts tremendous effort for each student,” says Connell, who works alongside Assamagan at the African School of Physics. “No one can imagine where he finds the time for his enormous industry with its enormous quality. Mostly we are all in wonder.”