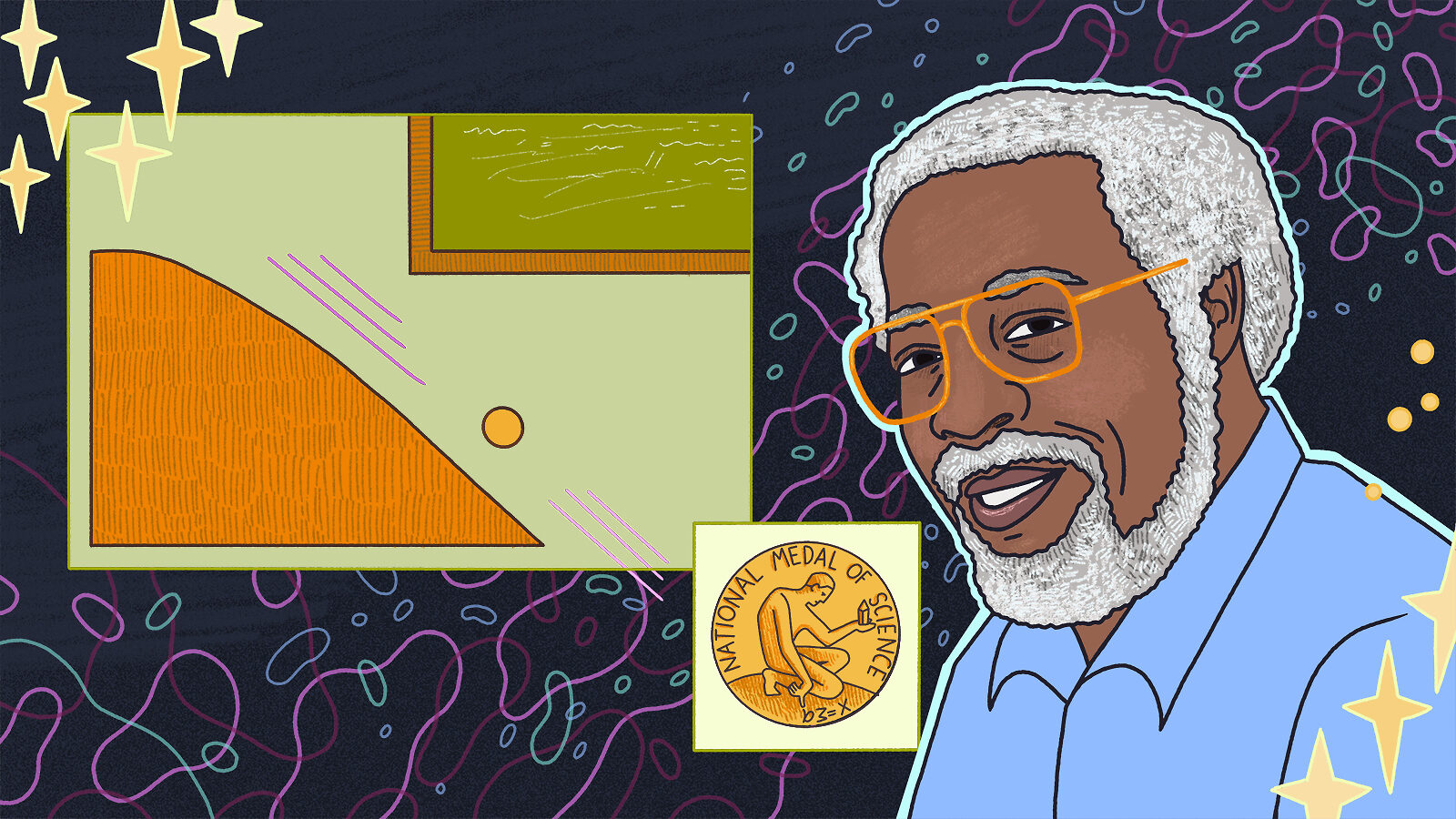

In the fall of 1968, a few weeks after the start of the new school year, high school physics teacher Freeman Coney conducted a demonstration that changed at least one student’s life.

All he did was roll a ball down a tilted surface. His students measured how far the ball had traveled and how quickly. Then Mr. Coney, as they called him, wrote an equation on the chalkboard that echoed what the students had observed, illustrating the relationship between distance and time.

The experiment was simple, requiring only a ruler, a stopwatch, the tilted surface and the ball. But it left an indelible impression on junior Sylvester James “Jim” Gates, Jr.

“This is the only piece of magic I have ever seen in the universe,” he says. “Before that, I always thought about mathematics as a game teachers taught us to play in school.”

But seeing Mr. Coney’s equation play out before his eyes, he realized that math was actually tied to tangible things that happened in the universe around us. “It was like learning to cast spells,” he says. “That’s the most magical moment from my Jones High experience—watching that experiment and becoming Harry Potter.”

Gates went to Jones High School, founded in 1895 as the first public school for Black students in Orlando, Florida. It was still segregated when Gates attended.

He recalls competing in chess tournaments with his classmates at other high schools—“We never lost a match,” he says—and noticing the racial disparities. “I remember on my first occasion of doing that, looking at the resources that were available to students who were not African American and comparing those to the resources available to kids at my school.”

After graduating from Jones as valedictorian in 1969, Gates headed to MIT. In his second year there, Gates and a few of his classmates started a tutoring program for MIT students called the Black Student Union Tutorial Program. He says it was during this tutoring that he realized he loved teaching. In 1972, he joined a summer program called Project Interphase that he was involved with for over a decade.

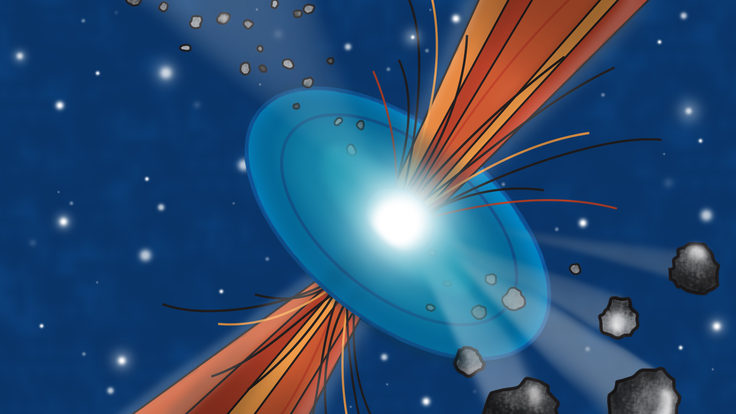

In 1973, Gates graduated with dual degrees in math and physics and then stayed at MIT for a PhD in physics. His dissertation was the first to deal with Supersymmetry.

In 1988, he became the first Black physicist to hold an endowed chair in physics at a major US university. In 2013, he received a National Medal of Science from then-President Barack Obama. Today, Gates is a professor at Brown University and an expert on Supersymmetry, supergravity and superstring theory. He is also currently the president of the American Physical Society.

Despite his numerous achievements, Gates describes himself as “just an ordinary, country theoretical physicist” who hasn’t forgotten his roots: Gates is still committed to ensuring young people have access to educational resources.

Returning to Jones High

In 2004, someone from Jones High contacted Gates about naming a new STEM award after him. Gates says he was shocked and humbled, and he committed to personally giving each recipient $1,000.

Kharis Hughes remembers the day she got the award in 2016 as a whirlwind, complete with a camera crew from the local news station. She’d been told ahead of time to dress up. But she didn’t know why, thinking it had something to do with her spot on the homecoming court. Instead, Gates was there to personally present her with a certificate and a check.

Looking back, she says she didn’t fully process how meaningful the award was. “It was one of those things where I feel like if I could go back now, I'd be like, ‘Oh, my God, thank you so much. You don’t know how much of a difference this made.’”

Hughes is now an academic advisor through Alabama State University’s TRIO Program, which serves low-income students, students with disabilities and students who will be the first in their families to attend college.

Hughes recalls how in high school many people, including Gates, devoted energy and resources to helping her become the person she is. Now, she says, “I want to be able to do that for other people.”

During his annual visit to Jones High, Gates shares stories with the students, answers questions, poses for photos and gives advice about what they can do with STEM degrees.

“It’s a very motivational thing for our students to see that there’s somebody who came from the same streets that he did,” says Allison Kirby, who has been principal of Jones High School since 2017.

Kirby says Gates’s legacy has also helped reinvigorate the school’s physics program. When Kirby started working at Jones High School, students who wanted to take physics had to sign up to take it online.

“It was unfair they didn’t have access,” Kirby says. “How did we have this world-renowned physicist from Jones High School, and Jones didn’t have physics?”

Over the next few years, Kirby helped secure not one, but two full-time physics teachers—a feat made all the more impressive by the fact that Jones is the smallest high school in Orange County. Kirby says Gates helped connect her with physicists from nearby universities.

Physics is now the senior science at Jones High, meaning more students than ever are being exposed to it—and most of them seem to like it, Kirby says. “Our teachers have just really made it interactive and fun and [the students] feel like they’re learning something.”

Recently, the US Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory launched a new fellowship in Gates’s honor: the Sylvester James Gates, Jr. Fellowship. The five-year fellowship is awarded to early-career researchers and is aimed specifically at physicists who were first-generation college students or who came from backgrounds traditionally underrepresented in theoretical physics.

Like summer camp for math

In addition to maintaining a lasting relationship with Jones High School, as well as training students and postdocs in his own lab, Gates also runs a summer program to mentor young physicists.

In 1999, noting the dearth of theoretical physics research opportunities for undergraduate students, Gates and University of Iowa physicist Vincent Rodgers started the Summer Student Theoretical Physics Research Session, or SSTPRS, with just two students. Gates’ graduate students help with SSTPRS voluntarily, when they have time, so the number of students fluctuates from year to year, but the program continues. In 2020, they had 25 students. In 2021, nine.

The students spend a month living at one of the host universities—so far, these have included the University of Maryland, Brown University or the University of Iowa. They spend several hours a day getting a crash course in high-level math taught by Gates or a colleague. Gates says it’s like summer camp, “except that instead of a bunch of athletic activities, it’s mathematical.”

After developing a mathematical toolbox during the month-long residency program, students have the option to work remotely in groups on long-term theoretical problems that Gates has carved out of his own research. “It’s authentic research,” he says. “We’re answering questions nobody in the world has answered previously.”

Over the next several months, the students organize group meetings, fine-tune each other’s equations and check in with Gates or his colleagues if they get stuck. “But they’re the ones driving the solution to the problem,” he says, noting that the length of the calculations they’re solving is typically what postgraduate researchers would tackle.

Once the students finish the calculations, Gates and his research team make sure the math checks out, and then he analyzes the work—picking out the narrative theoretical threads and weaving them into publishable manuscripts. When he publishes the papers, which he says happens about 30% of the time, he always includes his young collaborators as co-authors.

“I wound up publishing papers with high school students—on string theory, of all things,” he says.

Because of the pandemic, the 2020 and 2021 programs were entirely remote and conducted through Zoom, which gave them a different dynamic than the usual, immersive experience—although it did open the program to a wider range of students, including one in Saudi Arabia and three in Hong Kong.

“It was a little more difficult on Zoom,” says Ricco Venterea, a Cornell University astrophysics student and 2021 SSTPRS participant. “But it wasn’t impossible.”

He says he appreciated how the use of online features like breakout rooms still allowed the students to collaborate with each other, “because that’s what research is all about.”

One of the most powerful lessons he learned wasn’t just about math or physics: It was about taking charge of his education. “I remember Professor Gates saying, ‘You’re your own best teacher,’” Ventera says.

Fellow 2021 participant Jude Bedessem says his team’s research meetings with Gates managed to be both fun and productive.

“He made us feel valuable as coworkers, which I feel is pretty extraordinary given the fact that he is Jim Gates, and we’re doing research that undergrads don’t usually have access to,” says Bedessem, who is now studying physics and math at the College of William & Mary.

Bedessem is working on a remote research project and is looking forward to the possibility of their work being published someday. “Publishing in and of itself is really cool,” he says. “And publishing with Jim Gates is extraordinary.”

Gates says he has utmost confidence in the students. “We’re able to solve problems no one else can because we have the inspiration of these young people who constantly force us to think about things in different ways,” he says. “And that’s the secret for solving problems.”