Physicist Archana Sharma remembers the day in 1992 when her CERN supervisor, Georges Charpak, won the Nobel Prize. She had joined CERN in a time before the World Wide Web was in the public domain, and the Nobel prize announcement came in via fax.

“A technician came out of the workshop and said, ‘You know what, Georges, you won the Nobel Prize!’” Sharma says.

Sharma remembers the excitement of that day, along with a celebration that was a bit different than what she was used to. “In India, we don’t have this tradition of kiss on the cheek,” she says. “But then that day everybody was doing it and congratulating Georges. And Georges greeted me as well.”

At the time, Sharma was the only Indian citizen employed by CERN and just one of a handful of scientists of Indian origin at the European particle physics laboratory. She had taken a chance, leaving her home to develop technology for the largest high-energy physics experiment in the world.

She was recently recognized for all she has accomplished since stepping out of her comfort zone. Early this year, Sharma received India’s highest honor for Indians living abroad, called the Pravasi Bharatiya Samman Award.

The award, presented by the President of India, is given for exceptional contributions in professions like economics, altruism, journalism and science and technology.

“This award is a testament to our commitment and dedication towards making positive contributions,” says Sharma. “We have worked together to promote peace and development for all citizens, regardless of ethnicity or background, which has emerged from our strong Indian roots and our commitment to the philosophy of Vasudhev Kutumbakam—[a Sanskrit phrase that means] ‘The world is one family.’”

Sharma came to Geneva for the first time in 1987 for a short-term internship to work in Charpak’s group on a new detector technology. Afterward, she returned to Delhi, where she started both a PhD in particle physics and a family. “I earned the privileged title of a mother and a doctorate together,” she says.

But the fascination of being around physicists, data analysts, engineers and others working together towards a common goal never left her mind. Soon after completing her studies, she applied for and won a three-year fellowship at CERN.

“Coming to Geneva again for three years, with my husband and son in tow, was a major event in my life,” Sharma says.

From a tight-knit family, she says it was a huge step for both her and her parents for her to move so far away from them. “For my parents, it appeared as if I had gone to another planet,” she says. “Even though I was accomplished, even with a PhD, in an unknown city I was this shy, almost scared mother who was trying to find the light of day.”

Sharma says one of her biggest challenges was imposter syndrome, particularly with hands-on detector work. To develop her expertise, she decided to pursue a second PhD at the University of Geneva, where she focused on experimentation and studying gas detectors for radiation.

That was when she started to express herself with fewer inhibitions. “I mustered up the courage to say that I wanted to build a lab and asked for services for a small dump truck to clean up an area where I could start this lab,” she says.

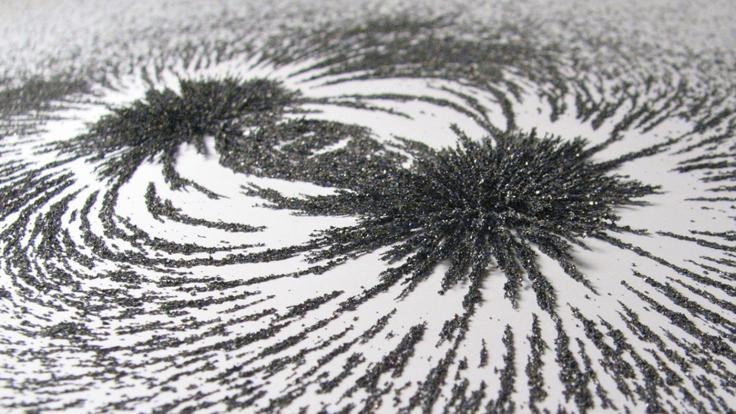

Sharma’s new lab was approved, and she and her team started building prototypes for a new type of muon detector to sit in the endcap for the CMS experiment. The new detectors—called RPCs—would eventually help physicists discover and study the Higgs boson.

The success of her lab’s work emboldened Sharma even more. In 2009, she decided to start R&D on another new type of detector technology called Gas Electron Multipliers, or GEMs. These detectors would be able to cope with the high collision rates—and high radiation—at the heart of CMS.

But convincing her colleagues to bring in an innovation was more challenging, she says. “Of course, ‘Why fix it when it ain’t broke?’ was the first reaction.”

But she believed that for an experiment scheduled to continue running until nearly 2040, “a change was needed.”

Today, more than a hundred GEMs are already inside the CMS detector, and scientists will install around 500 more over the next few years.

Beyond thinking about the future of the experiment, Sharma was also thinking about the future of physics. She made an effort to involve students in her projects.

“There was a time we had students from India, South America, the United States, China, etc., all working together,” she says. “There are always projects on the back burner—especially with projects that are needed but we do not have time and resources to do them—and students can learn a lot by contributing to them with proper guidance.”

Jeremie Merlin, now a research fellow at CERN, was one such student. He became involved in building and testing GEMs for the CMS detector with Sharma 12 years ago. “That’s the reason I chose to become a detector physicist, among all the possibilities that make the wide world of particle physics,“ he says.

Sharma also helped create official CERN programs so that more students from outside Europe could come work at the lab. In 2001, CERN had the first official summer student from India. Today, more than 250 scientists and students from India, and over 400 of Indian background, are associated with CERN.

During her acceptance speech for the Pravasi Bharatiya Samman Award, Sharma recognized the importance of science in removing national barriers, as it had done for her and all the students who aspire to pursue science globally.