When deciding between becoming a physicist or a musician, Hitoshi Murayama thought musician was the easy choice.

With years of experience rocking out with a band playing Pink Floyd- and Genesis-inspired ballads in high school and playing the double bass in venues around Tokyo in college, Murayama was ready to leave his undergraduate physics degree behind. But as he played more and more gigs, fellow musicians warned him about how tough it could be.

He remembers changing his mind, thinking maybe it would be easier to make a living doing physics instead. “But that wasn’t really true, in the end,” he laughs.

He’s done it, though. Murayama is a faculty scientist in the Physics Division at the US Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and a faculty member in the physics departments at the University of California, Berkeley and is a University Professor at the University of Tokyo. He was the first director of the Kavli Institute for Physics and Mathematics of the Universe based in Kashiwa, Japan. Earlier this year, he was awarded a fellowship from the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Throughout his career, Murayama has challenged expectations and cultivated communities of scientists, earning him a reputation as both a brilliant physicist and an exceptional communicator.

Carving his own path

Leaving his rock star dreams behind, Murayama rekindled his love of physics as he studied for graduate school entrance exams. He applied to study particle physics at the University of Tokyo.

Murayama was especially excited about studying aspects of particle physics that could be observed and tested through experimentation. But once he arrived at University of Tokyo, he soon realized his research interests didn’t align with those around him. “Everybody in grad school was studying string theory except me,” he says. “I felt very isolated.”

He was considering quitting when a visiting scientist gave him new hope. Kaoru Hagiwara, a physicist from the High Energy Accelerator Research Organization, or KEK, in Tsukuba, Japan, delivered a series of lectures on subatomic particle research. Murayama was hooked. “I asked him right away–I begged him–to work with me,” Murayama says.

Hagiwara said he couldn’t teach until he returned from a two-year sabbatical in the UK.

For the next two years, Murayama continued through his graduate program, studying condensed-matter physics and superconductors and clinging to the hope that Hagiwara would return and mentor him through the end of his doctorate research.

When Hagiwara returned, Murayama immediately reached out. Hagiwara told Murayama that he preferred to teach more than one student at a time. So, as Murayama traveled the country giving invited talks at other research institutes, he also recruited students to work with Hagiwara. In the end, he enlisted seven students to join him in Tsukuba to learn from Hagiwara and his colleagues at KEK in a month-long intensive course.

Because it took him so long to start learning about the science he wanted to study, Murayama had only one year in which to complete his doctorate research. “I wasn’t sure I was going to graduate,” Murayama says.

He did, despite the fact he didn’t write a single research paper with any of his thesis committee members, some of whom were rather skeptical of Murayama’s scientific prowess.

The experience taught Murayama lessons that he now passes on to his own graduate students: mainly that it’s important to be able to believe in and take ownership of one’s decisions. “I like to give my students space to pursue whatever they want to do, instead of being told what to do,” he says.

Director of the universe

After earning his PhD, Murayama spent two years in a postdoctoral position at Berkeley Lab before becoming an assistant professor at UC Berkeley. He spent the next decade planting roots in California while launching a productive research career studying subatomic particles and the theory of Supersymmetry.

In 2007, two professors from the University of Tokyo traveled to California to ask Murayama for help with a proposal for a new research institute in Japan.

The proposal was for a new mathematics and physics institute that would be operated over a minimum of 10 years through the University of Tokyo, funded with a $130 million grant from the Japanese government’s World Premier International Research Center Initiative. Not only did the professors want Murayama’s help crafting the proposal, they also wanted him to serve as the institute’s director.

Murayama quickly rejected their request. “I told them it sounded like a good opportunity, but I was happy in Berkeley, and I didn’t intend to move back to Japan,” he says.

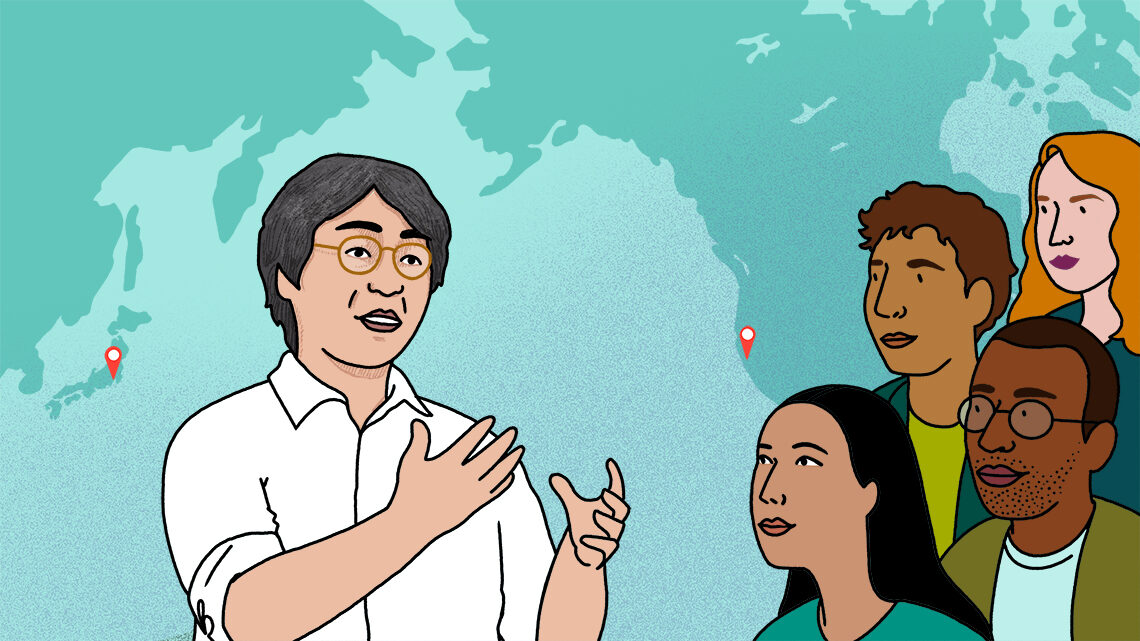

But the visitors persisted. Encouraging them was fellow physicist Hirosi Ooguri. Ooguri first met Murayama at the University of Tokyo in the mid 1980s. He says he came to appreciate Murayama’s talent for bringing people together in the early 2000s, when he observed Murayama’s work on the Kamioka Liquid-scintillator Anti-Neutrino Detector, known as KamLAND, an anti-neutrino detector experiment based on the island of Honshu, Japan.

The KamLAND project was an international collaboration primarily between American and Japanese research institutions. Murayama had a knack for helping the culturally different groups of researchers understand one another and work effectively, Ooguri says. “That earned him a lot of respect and credibility among both Japanese and American experimentalists.”

So when it came time to find someone to serve as director of the prospective new research institute, Murayama “was a unanimous choice,” Ooguri says. “I knew Hitoshi, and I knew he would be the right person.”

After several phone calls, Murayama agreed to help with the proposal, though he had little confidence it would be accepted in the face of stiff competition from other scientific fields. “I was actually quite convinced that our proposal was not going to fly,” Murayama says. “I was shocked when it was approved.”

In 2007, Murayama became the founding director of the Kavli IPMU. With his new position came the responsibility to build a new international research community. But such work comes naturally to Murayama, Ooguri says. “He is a great communicator, and I think it comes from his sincere desire to advance science. He explains the science extremely well and with such enthusiasm that it gets people excited about it.”

Murayama led the institute for 11 years, before being succeeded by Ooguri. Murayama says he thinks his experience creating the community there helped him to become a better mentor to students, and “hopefully gain a bit of a reputation for being an inclusive person who provides a safe environment,” he says.

He’s still busy mentoring students and managing multiple scientific collaborations. “I don’t know how he does it because he takes on so many different things,” Ooguri says.

Unfortunately, that means one thing has been put to the side for Murayama: “I don’t get to play the double bass as much as I would like to,” he says.

It does stay in his living room, though, just in case he ever feels the need to rock out.