They love to tinker with machines, big and small. They love to analyze data. And yes, they even love it when things go wrong or when the data say something different than expected. It’s not a setback: It’s interesting.

They are 10 early-career experimental particle physicists and astrophysicists. And they are living and working in an exciting time of both huge experiments, such as those at the Large Hadron Collider, and small ones, such as a balloon mission that scientists will use to search the skies for evidence of dark matter.

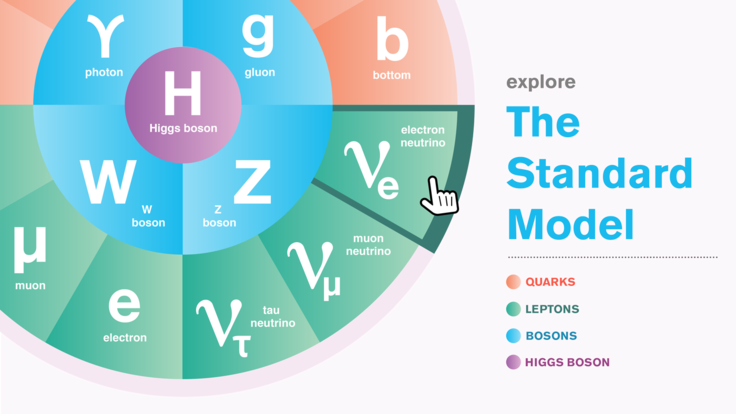

As big questions remain unanswered in the field—how the universe began and expanded, or the nature of dark energy, dark matter, the Higgs boson, neutrinos and more—these physicists know the answers lie in data, if they can only develop elegant experiments that look in just the right place.

“There’s a bit of a thrill factor right now in physics,” says Zeeshan Ahmed, project scientist and Wolfgang Panofsky Fellow at the US Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. “Theoretical models suggest where to look for certain answers, but some experimental measurements don’t match. There’s a tension, and it’s exciting.”

As tenure-track (or recently tenured) faculty, these scientists are shaping their own research programs, designing their own experiments, and building collaborations around the world. All the while, they are taking on the responsibility not just for answering questions, but for figuring out which questions should be asked.

“That’s really exciting, but also a little scary,” says Peter Sorensen, senior scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. “You’re helping define a field, and in the end, you might be wrong.”

They are also becoming mentors to the next generation of physicists, both at work and at home, where they try to find the right balance of professional life and family time. “I look at student data plots while nursing while trying to figure out what to make for dinner,” says Naoko Kurahashi Neilson, associate professor of physics at Drexel University in Pennsylvania.

More than a few are worried that upcoming experiments might not ultimately find the answers they are looking for. But they are also confident that the answers will eventually come.

“A lot of sought-after answers might be within reach experimentally in the not-so-distant future,” says Andrew Mastbaum, assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Rutgers University in New Jersey. “It’s a very exciting time.”

Zeeshan Ahmed

Title/Institution

Project scientist and Wolfgang Panofsky Fellow, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California

Current scientific focus

He studies the cosmic microwave background (CMB)—radiation left over from just after the Big Bang—with specialized cameras and telescopes to better understand the origin of the universe. He is a member of the BICEP/Keck, South Pole Telescope (SPT-3G), Simons Observatory and CMB-S4 scientific collaborations.

How he became a physicist

“I kind of stumbled into it,” he says. He was a mechanical engineering major in college when he heard a talk by physicist Alan Weinstein about the engineering of the LIGO [Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory] project. “I ate it up,” he says. He ended up in physics graduate school at Caltech working on dark matter detection, and eventually became fascinated with the CMB and understanding how the universe started.

Favorite part of the experimental process

Tinkering with a problem, then walking away from it to find a better way to tackle it. Some experimental instrumentation problems require complicated solutions. On the other hand, he says, “sometimes it’s as simple as duct tape.”

What’s most surprising about being an experimentalist

It can be both chaotic and boring: Being an experimentalist requires both lab and management skills. “There’s a large amount of work in Excel spreadsheets that I never thought I would be doing,” he says.

What keeps him up at night

“My kid keeps me up at night.”

What he would say to a young person who is interested in becoming a physicist

“Do it. It’s incredibly fun.” If you’re not sure if physics is right for you, try an internship or a Research Experiences for Undergraduates program.

When he’s not conducting experiments

You can find him outdoors or hanging out with his wife and 18-month-old toddler.

Marcelle Soares-Santos

Title/Institution

Assistant professor of physics, Brandeis University in Massachusetts

Current scientific focus

Dark energy. She’s using measurements from gravitational-wave events and traditional astronomy methods to map the rate of the expansion of the universe, thought to be driven by dark energy. She is a member of the collaborations for the Dark Energy Survey and the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope.

How she became a physicist

“Ever since I can remember, I was a very curious person,” she says. “At the end, if you keep asking yourself the why and the how of the universe around you, you are bound to end up in the world of physics.” She originally hoped to be a theorist, but in graduate school she found she enjoyed the large experimental collaborations. “With dark energy, the ball is really in the experimentalists’ court,” she says. “If we don’t understand observational data, we can’t guide new theories.”

Favorite part of the experimental process

Going from an abstract concept to building an efficient experiment to find the right information you need to solve the puzzle. “When you see it working, it’s fascinating. Analyzing the data and seeing the physics pop out—that’s really cool.”

What keeps her up at night

The discrepancy in measurements of the rate of the expansion of the universe. “Either all of us are missing something, or it’s the experimental set-ups. It’s very hard to think what it could be.”

When she’s not conducting experiments

She’s busy working to reach out to groups that are underrepresented in physics to help expand and diversify the field.

Fun fact

From ages 4 to 14, she lived in a small village in the middle of the Amazon forest. “It’s a very different world from living in a big city,” she says. “You know everyone, so there’s a sense of community.”

Naoko Kurahashi Neilson

Title/Institution

Associate professor of physics, Drexel University in Pennsylvania

Current scientific focus

Using the IceCube Neutrino Observatory at the South Pole, she is interested in finding out whether black holes or other energetic objects in space emit particles called neutrinos.

How she became a physicist

As a kid in the 1980s, she remembers seeing a group of NASA scientists cheering on television. “They were cheering for something that wasn’t going to benefit them or make them wealthy,” she says. “The thought of people coming together just for the sake of discovery seemed very noble to me.” She was good at math and interested in big questions, and in graduate school she had the chance to go to the Bahamas to use acoustic detection to listen for neutrino interactions. She has been hooked on searching for the particles ever since.

Favorite part of the experimental process

When she discovers something irrefutable. “The laws of physics apply equally to everybody, no matter who you are,” she says.

What’s most surprising about being an experimentalist

Traveling to exotic locales like the Bahamas and the South Pole. “Sometimes I feel like James Bond, and other times I think, no, this is not like James Bond at all,” she says. And while many people have a vision of physicists as being sci-fi geeks or eccentric in some way, she often tells people that’s not the case. “I’m an ordinary person,” she says. “I tell people they don’t have to fit into that culture if they want to do physics.”

What keeps her up at night

Because she is trying to locate individual sources of neutrinos in space, she wonders: What if there are so many neutrino sources everywhere in the sky that we won't be able to distinguish any single source?

What she would say to a young person who is interested in becoming a physicist

Don’t slack off in math—it’s an important building block. As an undergraduate, network and find people who will take you under their wing.

When she’s not conducting experiments

She spends time with her three kids and listens to country pop music. “I don’t like good country music,” she says. “I like the bad, cheesy country pop.”

Chao Zhang

Title/Institution

Physicist, Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York

Current scientific focus

Neutrinos, the second most abundant particles in the universe, after light. He has been involved or is currently involved in several neutrino experiments, including DUNE, MicroBooNE, ICARUS, Daya Bay, PROSPECT and KamLAND.

How he became a physicist

His graduate school adviser at Caltech convinced him to try out particle physics at the KamLAND neutrino experiment in Japan. He was fascinated by how the experiment illuminated how the flux of neutrinos from the sun was different than what was predicted. “You can create an experiment on Earth but solve something in the sun. That blew my mind,” he says.

Favorite part of the experimental process

Because physics experiments often include hundreds of people from around the world who are experts in different areas, he is able to continually learn new skills. “And when your experiment succeeds and you know some secret of nature that nobody else knows—that’s an incredible feeling,” he says.

How he explains his job to friends and family

He describes neutrinos and why they are important, but when someone asks what they can use a neutrino for, “that usually ends the conversation,” he says. “Many people want to see immediate returns in value, but part of our job is to convince people that it is still valuable to do fundamental research.”

What he would say to a young person who is interested in becoming a physicist

Don’t get overwhelmed by big experiments. “Be patient, and pick up a few things at a time.”

When he’s not conducting experiments

He enjoys watching soccer, often while chatting online with friends in China. He also enjoys reading, especially George R. R. Martin’s series A Song of Ice and Fire.

Fun fact

His father was an engineer specializing in the construction of underground mines. Chao did not realize that, so many years later, he would be part of so many experiments housed in these mines. “I wish I had inherited his knowledge,” he says.

Kerstin Perez

Title/Institution

Assistant professor of physics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Current scientific focus

Studying cosmic particles to look for evidence of dark matter interacting with itself. She uses astrophysical X-ray observations to search for evidence of dark matter interactions, and she’s leading the silicon detector program for the GAPS experiment, which will use a balloon to search for antideuteron and antiproton evidence of dark matter annihilation.

How she became a physicist

Growing up, she was interested in drawing, painting and building, and thought she would study fine arts. When she took physics in high school, she saw how math connected with the world. And when she first conducted research in college, she saw how her creative side could be used in building and deploying experiments.

Favorite part of the experimental process

She was in graduate school, conducting research at CERN, when the Large Hadron Collider was first turned on, and she knew she wanted to experience building an experiment from scratch. Now she is helping to do that with the GAPS experiment. “I like building things with a small group of people who are all trying to get something to work,” she says. “I find that really exciting.”

What she would say to a young person who is interested in becoming a physicist

“Explore your creativity.” Although becoming a physicist typically requires following a well-defined academic path, she says, it’s the creative aspect that will help you take something that doesn’t exist and make it a reality.

When she’s not conducting experiments

She recently had a baby, so she spends much of her time “raising a tiny human,” as well as seeing live music and art. She’s also an avid fan of the Philadelphia 76ers basketball team.

Fun fact

She’s West Philadelphian, born and raised—from the same neighborhood as Will Smith and Boyz II Men.

Jax Sanders

Title/Institution

Assistant professor of physics, Marquette University in Wisconsin

Current scientific focus

Disturbances in space-time called gravitational waves. Designing subsystems for interferometers, like those used in LIGO [the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory], and designing new gravitational-wave detectors.

How they became a physicist

They went to a small liberal-arts college and were interested in chemistry, but when a chemistry experiment “literally blew up in my face,” they applied to a Research Experiences for Undergraduates program at LIGO Hanford. It was there they understood just how sensitive these experiments were, and how any motion could affect the outcome of the experiment. “The world is constantly moving, and you never really notice until you look,” they say.

Favorite part of the experimental process

Debugging. “I love building instruments,” they say. “I never stop learning and am constantly updating my skill sets. And when there’s a system that’s not quite working, it’s a fun puzzle.”

What’s most surprising about being an experimentalist

How much it has in common with trade work. “At LIGO, we get along really well with the pipe fitters. We have a similar attitude of ‘go in and get your work done.’”

What keeps them up at night

“How did the universe actually start?”

What they would say to a young person who is interested in becoming a physicist

Nail down conceptual learning, and don’t be afraid to use your hands and make mistakes. “Making small mistakes is how you learn,” they say.

When they are not conducting experiments

They like to draw and play games—both video games and role-playing games, like Dungeons and Dragons.

Fun fact

They have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, which they were diagnosed with as an adult. “It has made me a better educator,” they say. “I can speak more to students who have special accommodations.” They also have a tattoo of the first gravitational-wave signal ever detected, GW150914, the result of the merger of two black holes.

Laura Jeanty

Title/Institution

Assistant professor of physics, University of Oregon

Current scientific focus

Looking for long-lived particles on the ATLAS experiment at the LHC. “It’s exciting, because these particles are the most likely place for new physics to be hiding,” She is also co-convening the ATLAS group that searches for evidence of Supersymmetry—a theory in which every known particle is paired with a massive superpartner—and is helping to build a new tracker for the ATLAS experiment.

How she became a physicist

She double-majored in physics and geology as an undergraduate, but being “both stubborn and curious” led her to ask questions about the universe and ultimately end up in physics. “It’s incredibly satisfying to be able to ask and attempt to answer questions about the world as one’s career,” she says.

Favorite part of the experimental process

Debugging everything from hardware to software to data plots. “I love the interface of the detector and the analysis of data,” she says. “It’s amazing to be a part of building an instrument and then participate in data being produced and recorded. I enjoy looking at data and trying to make sense of it, especially when it doesn’t match what we expect.”

What keeps her up at night

The LHC experiments’ most famous discovery so far has been the Higgs boson, the particle associated with the field that gives other fundamental particles their mass. She wonders, “Are we going to find something new at the LHC after the Higgs boson?”

What she would say to a young person who is interested in becoming a physicist

It’s more important to learn to ask the right question than it is to be able to answer other people’s questions.

When she’s not conducting experiments

She’s chasing around her 3-year-old son and answering his “infinite series of ‘why’ questions.” She also enjoys hiking and visiting local wineries.

Nhan Tran

Title/Institution

Wilson Fellow and associate scientist, Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Illinois

Current scientific focus

Studying the Higgs boson and searching for dark-sector particles at accelerator-based experiments, and working at the intersection of electronics, computing and artificial intelligence to amplify the capabilities of experiments like those at the Large Hadron Collider.

How he became a physicist

His father was a physicist, and Nhan always enjoyed math and science. As an undergraduate he worked on a particle physics experiment and knew that was the path for him.

Favorite part of the experimental process

“You’re constantly learning,” he says. Once you solve one problem, another one presents itself. That requires a “jack-of-all trades” skill set, which he enjoys pursuing.

What’s most surprising about being an experimentalist

“A lot of people think we sit in a dark room and wait for a lightbulb to appear,” he says. Day-to-day explorations provide knowledge in small increments, often through failure.

What keeps him up at night

“Am I spending my time on the right things?”

What he would say to a young person who is interested in becoming a physicist

Learn to program. “People are often surprised to hear this, but it’s an important skill to be a productive, young physicist doing data analysis.”

When he’s not conducting experiments

He’s playing and watching sports. He enjoys physical activity and competition, but he also likes the way sports are ultimately quantifiable and conclusive.

Fun fact

He has recently gotten into taking on Ninja Warrior obstacle courses with his two young kids and fellow physicists.

Peter Sorensen

Title/Institution

Senior scientist, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California

Current scientific focus

The search for dark matter. He has worked on the Large Underground Xenon experiment and its follow-up, LUX-ZEPLIN. He recently received an award to freeze liquid xenon in a detector to better identify radon within it to increase the sensitivity of the experiment.

How he became a physicist

“I was the kid who would take apart my friend’s toy to figure out how it works, which wasn’t always well received,” he says. He was always curious about the natural world, and detectors seemed like a natural way to explore it.

Favorite part of the experimental process

He loves figuring out which instrument he and his colleagues need to build to find the answer they are looking for, and how they are going to make design choices that will ultimately give them a rich data set. “I love being faced with something where I don’t know the answer,” he says.

What keeps him up at night

Not the big questions, but rather: Why isn’t the detector working properly? What glitch do I need to fix?

What he would say to a young person who is interested in becoming a physicist

His undergraduate adviser told him flat out: “Don’t do it.” Wages are low, jobs are scarce, and you might spend years in the field without getting a tenured job anywhere. While this is true, he says, he wouldn’t say that to someone. “I would say, good for you, just make sure you really want to do it.”

When he’s not conducting experiments

He runs in the mountains and makes homemade wine. He uses “any grape that’s well-grown” and makes both red and white wines.

Andrew Mastbaum

Title/Institution

Assistant professor of physics and astronomy, Rutgers University in New Jersey

Current scientific focus

The physics of neutrinos—specifically, whether new types exist beyond the types physicists know about. He works on neutrino detection experiments, including SBND, MicroBooNE and DUNE. “There’s so much we don’t know about neutrinos and their role in the universe,” he says. “It’s a very exciting place to be now.”

How he became a physicist

He was always interested in both technology and in understanding how things work, so experimental physics “was a perfect marriage of these interests.”

Favorite part of the experimental process

“It’s all so fun,” he says. Each day is different: Some days he’s trying to understand how to look for new physics in experimental data, while other days he’s in a mine, a mile underground, bolting stuff together for a new experiment.

What keeps him up at night

Although he and his collaborators strive to build experiments that allow them to ask the right questions, he worries that “nature might have tricks in store that could muddy the waters. If neutrinos interact in a new way that we didn’t anticipate, how could we know for sure what we are seeing?”

What he would say to a young person who is interested in becoming a physicist

Talk to people involved in the field and get a sense of what the latest problems and questions are. “Most people are happy to talk about their work and are willing to share their perspectives,” he says.

When he’s not conducting experiments

You can find him cooking, reading a good book, cycling or hiking—or any activity that helps him stop thinking about a problem for a bit so he can return to it with a fresh mind.

Fun fact

As an undergraduate student, he was into swing dancing, and that’s how he met his wife. “Physicists can dance, too,” he says.