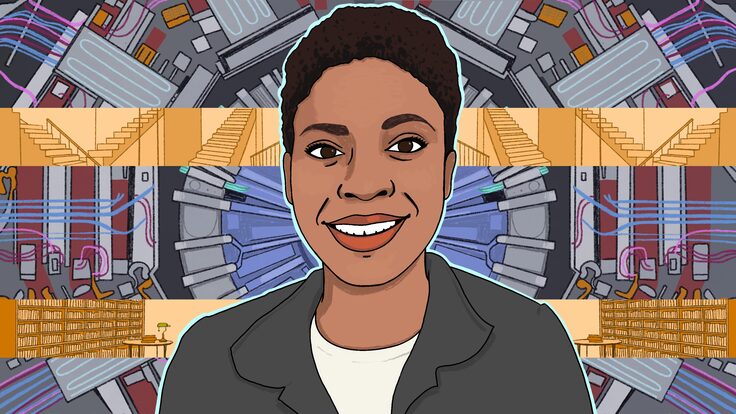

At the age of 16, Kira Burt dropped out of high school in Spokane, Washington, and started working odd jobs in food service and retail. She couldn’t picture it then, but 16 years later, she would be sitting in a cleanroom at CERN, piecing together part of a detector, working on her PhD in physics.

Burt had always been curious. When she was a kid, she would get in trouble for mixing solutions from ingredients she found in the kitchen and the bathroom. She took apart alarm clocks and would poke around inside old cars at her grandparents’ autobody shop.

But at school, Burt struggled.

“Being a talented student only takes you so far, especially if you don’t go to class” Burt says.

Burt often skipped school to avoid the anxiety of being around her classmates. Her family’s poverty made her feel like an outcast. “Looking back, it’s silly, but at the time it was very serious,” Burt says. “It’s life and death to a teenager.”

After she dropped out, she earned her GED certificate and was planning to go straight to college, she says. “But the issues that I’d had in high school just followed me.”

Burt found it easier to work than to attend classes. At work, she discovered her natural talent for leadership. At 17, she took a job answering phones and taking orders at the local pizza shop. One year later, she was managing the place. By 23, she was a married homeowner making $48,000 a year.

“Working gave me the confidence and discipline that I didn’t have in high school,” she says. “I grew up during that time, and I was able to return to school at 25 and do really well.”

Burt signed up for community college classes and eventually transferred to a state university. Instead of mixing soaps and spices, she was now mixing reactants and catalysts for her chemistry major. But it was always the physics classes she was required to take that she found the most intriguing.

“So I changed teams and became a physicist,” she says.

Sixteen years after dropping out of high school, Burt landed in Geneva, Switzerland, with her entire life packed into two suitcases. For the next three years she worked on the CMS experiment at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN as part of her PhD program with the University of California, Riverside.

“It was amazing, and I wish I had appreciated it more while I was there,” she says. “Like, I would be in a cleanroom building a detector and get really frustrated because my code wouldn’t compile. But in retrospect, my job was so cool.”

“Take care of yourself as a human, and then you will do better science.”

But it wasn’t just the code that was challenging. Burt’s anxiety returned in full force, and she struggled to reconcile her old life with her new beginning. Her marriage fell apart as the stress of graduate school diminished her carefully cultivated work-life balance.

“Anxiety is a vicious cycle that’s hard to escape,” Burt says. “A lot of graduate students have untreated mental illness issues and need to spend more time taking care of themselves. If I had one piece of advice for students, it’s this: Take care of yourself as a human, and then you will do better science.” [See resources from the National Alliance on Mental Health.]

Burt found refuge in taking shifts in the CMS control room and working on the CMS pixel detector.

“One of the best treatments for anxiety is to just do something,” Burt says. “I was able to go to work and just be completely absorbed in resolving a difficult task.”

Burt decided that doing research at CERN was a passage and not a long-term career option for her. As her thesis defense loomed, Burt started seriously thinking about what she wanted to do with her PhD.

“With a science degree, I wanted to serve the public in some way,” she says. “I wanted to bring science to at-risk or underserved populations.”

A few months before graduating, she accepted a teaching position at a community college close to her hometown.

Today, Burt teaches introductory science and physics to students ranging from 16 to 60 years old at Spokane Falls Community College. She spends a large portion of her class teaching her students how to think scientifically and identify factually accurate information.

“I had a student who told me that she loves science, but she was afraid to love it because she thought she was bad at it,” Burt says. “She discovered that all it takes is hard work and a little confidence.”

One of Burt’s biggest goals is show her students that anyone can do science.

“My job is not something people going into graduate school are thinking about,” she says, “but I think it’s an important part of the community. As scientists, it’s our responsibility to bring science to people who are not exposed to it. We need to show students that science is for everyone.”