|

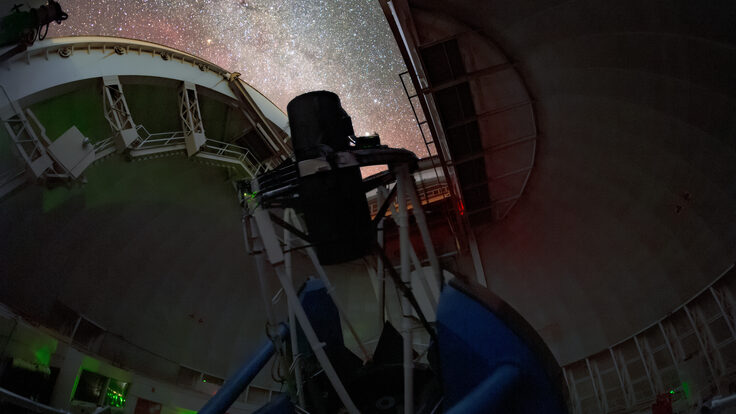

| Photo: Fred Ullrich, Fermilab |

Particle search on a shoestring

When Aaron Chou heard about an experiment in Italy that suggested the existence of an exotic particle as a candidate for dark matter, he was intrigued enough to go looking for it.

His first stop: the Fermilab cafeteria.

"The Fermilab cafeteria is a wonderful place to talk to people and ask around for available equipment," says Chou, a postdoctoral researcher at the lab. Working the lab grapevine, Chou (left, photo at bottom) and William Wester, a scientist in Fermilab's Particle Physics Division, scrounged enough parts to build their experiment on a shoestring budget. They borrowed a high-powered laser and scavenged a spare Tevatron magnet that could be operated at the existing Fermilab Magnet Test Facility, and kept the cost to about $30,000.

Their project, called GammeV (named for particle searches in the gamma ray to milli-electronvolt energy range), follows up on an experiment called PVLAS at Legnaro National Laboratory in Italy two years ago that suggested the existence of the ultralight particle.

The new experiment involves sending pulses of high-powered laser light through an opening in a magnet and toward a mirror. Normally, scientists would expect no photons, or light particles, to show up on the other side of the mirror. But if the new ultralight particle exists, some of the photons will convert into the proposed particle, travel through the mirror, and then convert back into photons, which scientists would detect on the other side. It would appear that light was passing straight through a wall.

Though scientists are skeptical of the suggested particle's existence, the results from Legnaro need to be checked, says Chou, who strayed from his usual area of researchcosmology to help put the project together. "It's unlikely but not impossible that the result is correct. If it is, it would be one of the most astounding discoveries of this century," he says. "Such a discovery could fundamentally change the direction of future experimental research in particle physics. The potential scientific impact and the low cost of the experiment make this a no-brainer. It's the type of experiment you just have to do."

Amelia Williamson

Click here to download the pdf version of this article.