Figuring out the nature of dark matter, the invisible substance that makes up most of the mass in our universe, is one of the greatest puzzles in physics. New results from the world’s most sensitive dark matter detector, LUX-ZEPLIN, have narrowed down possibilities for one of the leading dark matter candidates: weakly interacting massive particles, or WIMPs.

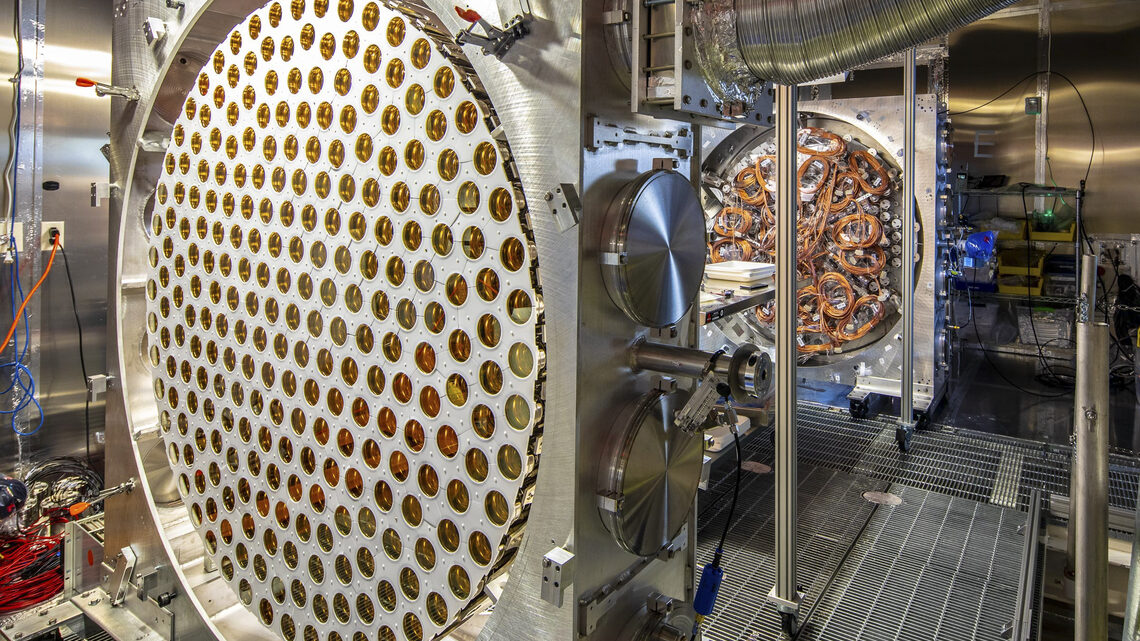

LZ, led by the US Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, hunts for dark matter from a cavern nearly one mile underground at the Sanford Underground Research Facility in South Dakota. The experiment’s new results explore weaker dark matter interactions than ever searched before and further limit what WIMPs could be.

“These are new world-leading constraints by a sizable margin on dark matter and WIMPs,” says Chamkaur Ghag, spokesperson for LZ and a professor at University College London. He says the detector and analysis techniques are performing even better than the collaboration expected. “If WIMPs had been within the region we searched, we’d have been able to robustly say something about them. We know we have the sensitivity and tools to see whether they’re there as we search lower energies and accrue the bulk of this experiment’s lifetime.”

The collaboration found no evidence of WIMPs above a mass of 9 gigaelectronvolts/c2 (GeV/c2). (For comparison, the mass of a proton is slightly less than 1 GeV/c2.) The experiment's sensitivity to faint interactions helps researchers reject potential WIMP dark matter models that don't fit the data, leaving significantly fewer places for WIMPs to hide. The new results were presented at two physics conferences on August 26: TeV Particle Astrophysics 2024 in Chicago, Illinois, and LIDINE 2024 in São Paulo, Brazil. A science paper will be published in the coming weeks.

The results analyze 280 days’ worth of data: a new set of 220 days (collected between March 2023 and April 2024) combined with 60 earlier days from LZ’s first run. The experiment plans to collect 1,000 days’ worth of data before it ends in 2028.

“If you think of the search for dark matter like looking for buried treasure, we’ve dug almost five times deeper than anyone else has in the past,” says Scott Kravitz, LZ’s deputy physics coordinator and a professor at the University of Texas at Austin. “That’s something you don’t do with a million shovels—you do it by inventing a new tool.”

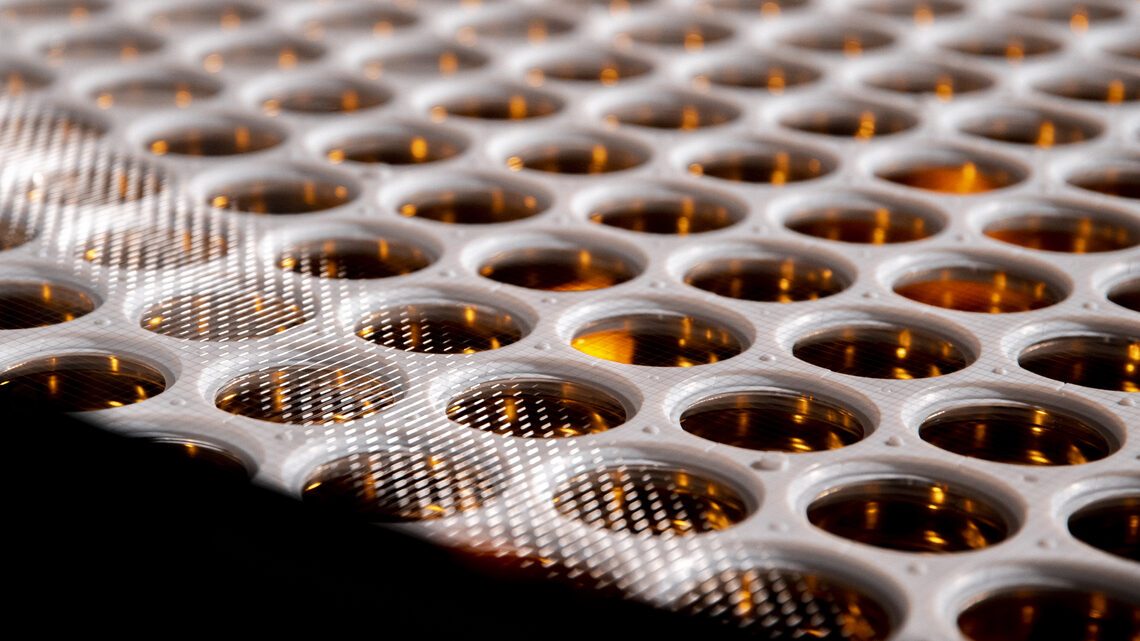

LZ’s sensitivity comes from the myriad ways the detector can reduce backgrounds, the false signals that can impersonate or hide a dark matter interaction. Deep underground, the detector is shielded from cosmic rays coming from space. To reduce natural radiation from everyday objects, LZ was built from thousands of ultraclean, low-radiation parts. The detector is built like an onion, with each layer either blocking outside radiation or tracking particle interactions to rule out dark matter mimics. And sophisticated new analysis techniques help rule out background interactions, particularly those from the most common culprit: radon.

This result is also the first time that LZ has applied “salting”—a technique that adds fake WIMP signals during data collection. By camouflaging the real data until “unsalting” at the very end, researchers can avoid unconscious bias and keep from overly interpreting or changing their analysis.

“We’re pushing the boundary into a regime where people have not looked for dark matter before,” says Scott Haselschwardt, the LZ physics coordinator and a recent Chamberlain Fellow at Berkeley Lab who is now an assistant professor at the University of Michigan. “There’s a human tendency to want to see patterns in data, so it’s really important when you enter this new regime that no bias wanders in. If you make a discovery, you want to get it right.”

Dark matter, so named because it does not emit, reflect or absorb light, is estimated to make up 85% of the mass in the universe but has never been directly detected, though it has left its fingerprints on multiple astronomical observations. We wouldn’t exist without this mysterious yet fundamental piece of the universe; dark matter’s mass contributes to the gravitational attraction that helps galaxies form and stay together.

LZ uses 10 tonnes of liquid xenon to provide a dense, transparent material for dark matter particles to potentially bump into. The hope is for a WIMP to knock into a xenon nucleus, causing it to move, much like a hit from a cue ball in a game of pool. By collecting the light and electrons emitted during interactions, LZ captures potential WIMP signals alongside other data.

“We’ve demonstrated how strong we are as a WIMP search machine, and we’re going to keep running and getting even better—but there’s lots of other things we can do with this detector,” says Amy Cottle, lead on the WIMP search effort and an assistant professor at UCL. “The next stage is using these data to look at other interesting and rare physics processes, like rare decays of xenon atoms, neutrinoless double beta decay, boron-8 neutrinos from the sun, and other beyond-the-Standard-Model physics. And this is in addition to probing some of the most interesting and previously inaccessible dark matter models from the last 20 years.”

LZ is a collaboration of roughly 250 scientists from 38 institutions in the United States, United Kingdom, Portugal, Switzerland, South Korea, and Australia; much of the work building, operating, and analyzing the record-setting experiment is done by early-career researchers. The collaboration is already looking forward to analyzing the next data set and using new analysis tricks to look for even lower-mass dark matter. Scientists are also thinking through potential upgrades to further improve LZ, and planning for a next-generation dark matter detector called XLZD.

“Our ability to search for dark matter is improving at a rate faster than Moore’s Law,” Kravitz says. “If you look at an exponential curve, everything before now is nothing. Just wait until you see what comes next.”

Editor's note: A version of this article was originally published as a press release by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.