It’s not often that big science comes rolling right through your town.

For those who live between Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York and Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Illinois, that’s about to happen. This summer scientists will transport a 17-ton ring from Long Island to Chicagoland in a complex move that will take more than six weeks.

The ring, used in an experiment that concluded in 2001 at Brookhaven, will find new life at Fermilab.

The machine was built on Long Island in the 1990s and is a giant electromagnet, one of the largest in the world. While most of it can be disassembled and brought to Fermilab on trucks, the core of the device—three steel and aluminum rings, with superconducting coils inside—must be transported in one piece and kept as flat as possible.

“It costs about 10 times less to move the magnet from Brookhaven to Illinois than it would to build a new one,” says Lee Roberts, professor of physics at Boston University and co-spokesperson for the Muon g-2 experiment, in a press release issued today. “So that’s what we’re going to do. It’s an enormous effort from all sides, but it will be worth it.”

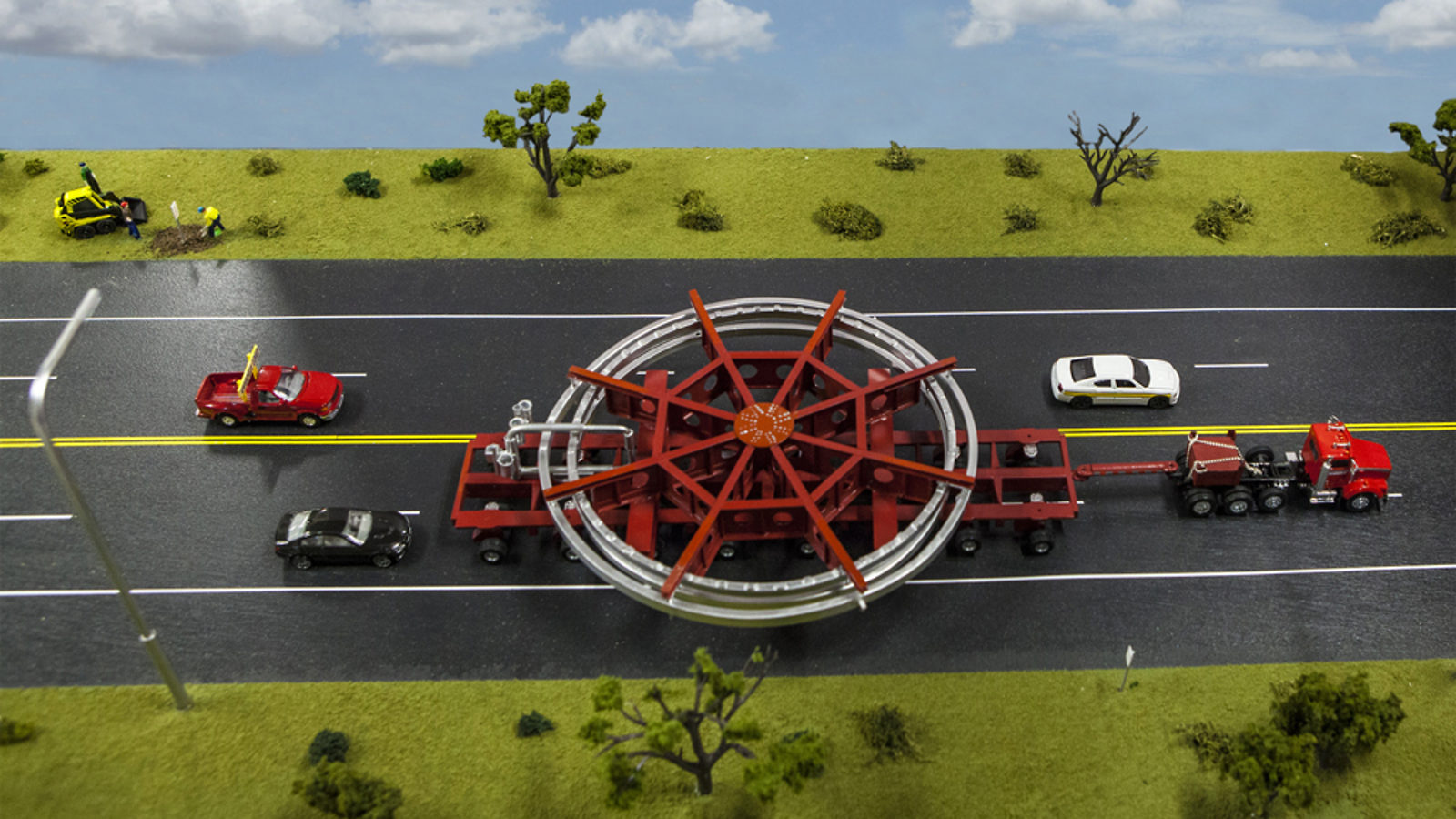

Beginning this June, the ring will be loaded onto a specially prepared barge, which will bring it around the tip of Florida and up the Mississippi River. After the water voyage, which is estimated to take six weeks, the barge will port in Lemont, Ill., where it will be loaded onto a truck designed to move large objects. The slow-moving truck (a model of which is pictured above) will take the ring to Fermilab over two consecutive nights, closing expressways with rolling roadblocks.

Once the ring arrives at the laboratory, it will become the centerpiece of the Muon g-2 experiment, which will study the “wobble” of muons in a magnetic field. The experiment follows a similar one conducted at Brookhaven in the 1990s, which found evidence for a deviation between the observed “wobble” and the expected value—but not enough to claim a discovery.

“Fermilab can generate a much more intense and pure beam of muons, so the Muon g-2 experiment should be able to close that margin of error,” says Chris Polly, project manager for Fermilab, in the press release. “If we can do that, this experiment could indicate that there is exciting science awaiting beyond what we have observed.”

In the coming weeks, the Muon g-2 webpage will be updated with information on the move and a map tracking the journey of the ring, including the Illinois leg of the journey pictured below.