An aerial view of the Diamond Light Source. Image courtesy of Harwell Science and Innovation Campus.

Editor’s note: This submission came to symmetry breaking from John Gilbey, a science and science-fiction writer featured in the April 2010 issue of symmetry magazine. Here he describes his experience visiting the Diamond Light Source, the UK’s national synchrotron facility. Gilbey often takes his inspiration for his fiction from trips to real-life laboratories, so be on the look-out for a familiar setting in one of his next tales.

When the Science Online London 2010 conference offered me the chance to tour the Diamond Light Source in Oxfordshire, England, my inner geek pushed me to sign up straight away.

Diamond is a new synchrotron facility built in the heart of rural England providing superb purpose-built facilities for a wide range of experimental work. The facility opened in 2007 and is being built in three phases. Crews built the first seven beamlines during the first phase, which the laboratory completed in 1997 on a budget of £263 million. Construction has now reached the second phase, during which the laboratory will use £120 million to build 15 additional beamlines by 2012.

At six o’clock on a beautiful September evening, a coach collected our varied group - science bloggers, writers, communicators and just plain old enthusiasts - from Euston Station in London. As we trundled westward through the rush hour traffic, it was clear that we were going to take a while to get there – and dusk was already falling when we spotted the massive, metal-clad doughnut of Diamond on the horizon.

Our host, Dr. Sara Fletcher, Diamond’s web and information manager, was clearly glad to see us arrive safely – and after a quick overview of the project she handed us over to her team of cheerful researcher volunteers for a tour of the facility.

Split into teams of six, we moved down the glazed high-level walkway that links the admin building to the source itself. We immediately had some excellent news – Diamond was in a period of down-time, so we were able to get a much closer view of the technology than would otherwise be the case.

After a safety briefing and a polite but firm request not to touch anything, we entered the Diamond Light Source itself. From the outside, the building looks impressive – from inside it is dramatically more so. The walls and ceiling curve away in such a gentle fashion that the overall scale of the building is dramatically reinforced.

Everything about the facility is on a grand scale: The storage ring, which gives the building its characteristic shape, is 581 metres in circumference. The floor area is 45,000 square metres – the size of 8 St. Paul’s cathedrals. The building contains 35,000 cubic metres of concrete and over 2,000 tons of steel – almost unimaginable quantities.

Unlike some science facilities I have visited, Diamond has a sense of one-ness – an integration of innumerable requirements in a single direction: It has clearly been designed to allow, and support, rapidly changing requirements and technologies. That these evolving needs can be accommodated within such a large scale managed facility is a credit to the project planners and managers.

The UK government reinforced its commitment to the project in the October 2010 Public Spending Review, during which it dedicated funding to the third phase of the project. In the current economic climate, and amongst significant cuts to public sector spending in the UK, this is a massive endorsement of Diamond’s importance. By 2017, Diamond will have a total of 32 beamlines – which will no doubt add significantly to the more than 1,000 publications already produced by the project.

Most impressive of all, however, are the people. Despite us being so late, our guides gave us an intimate, wildly enthusiastic look at an exceptional research facility – and gave us a glimpse of the kind of buzz that working in this environment generates.

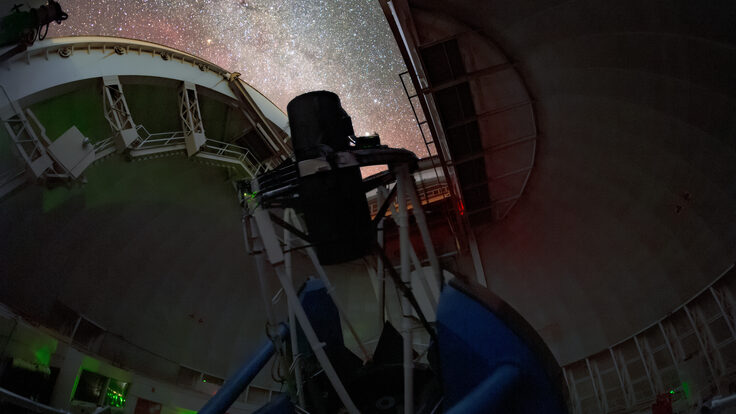

Inside the Diamond Light Source. Photo courtesy of John Gilbey.