Jenny Cutraro, science journalist and educator, worked until the last possible moment.

Soon, hundreds of families from around the Boston area would converge at the meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science for its public outreach event, Family Science Days. Kids interested in talking with scientists about their work would make a beeline for Science Storytellers, a conversation-based science communication program Cutraro had created.

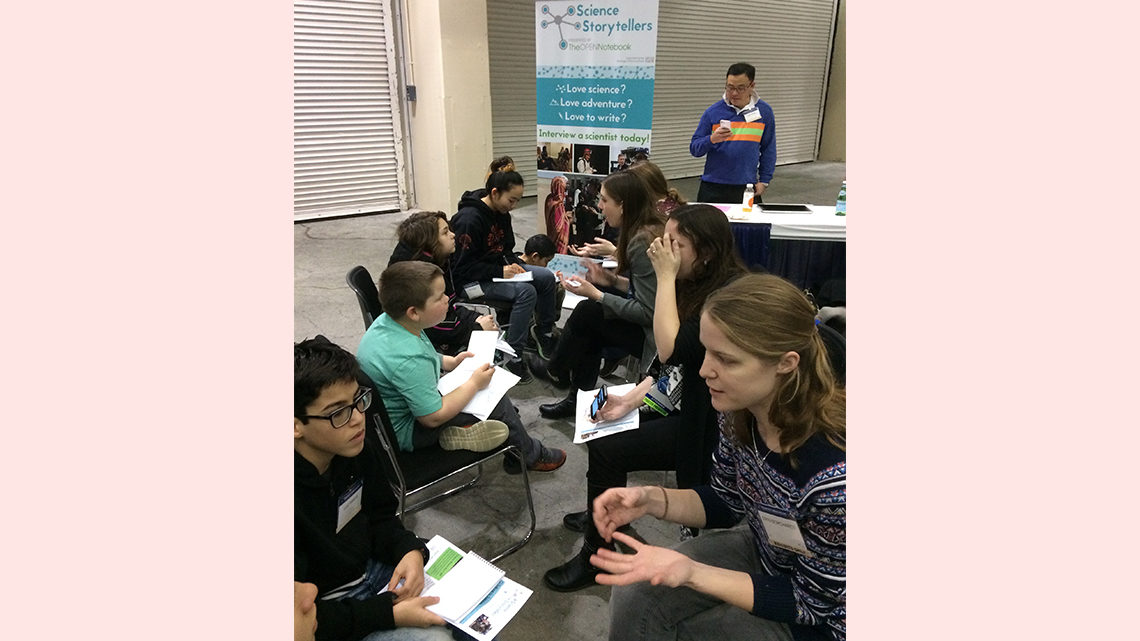

Earlier that morning at the Science Storytellers booth, Cutraro had given a brief pep talk to a group of scientists from a wide cross-section of disciplines who had volunteered to take the first one-hour shift answering questions from curious kids.

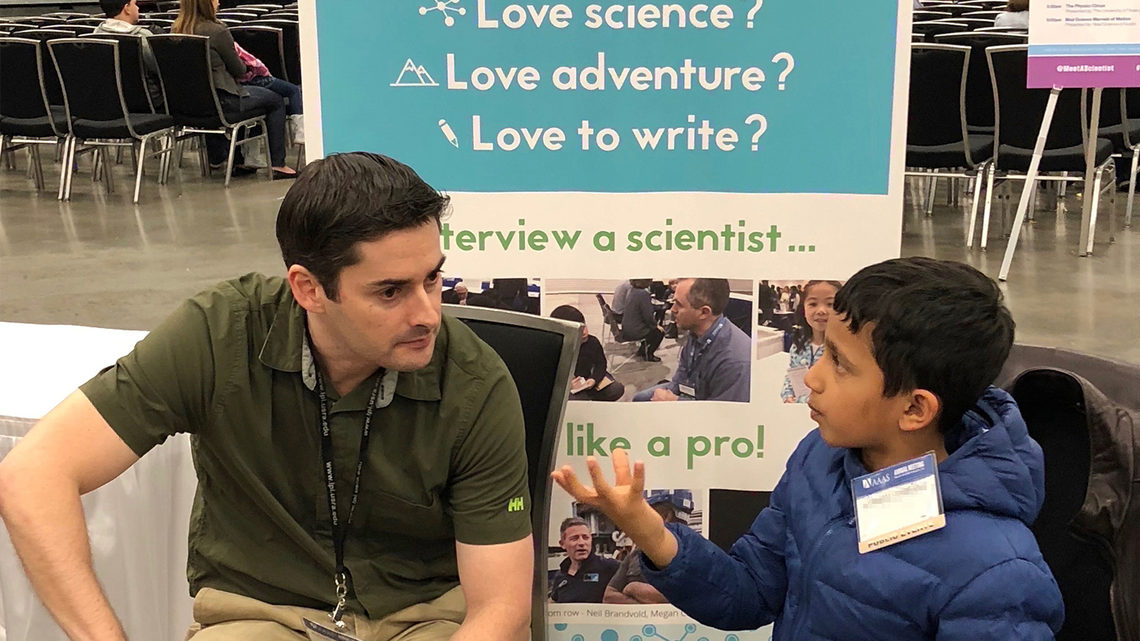

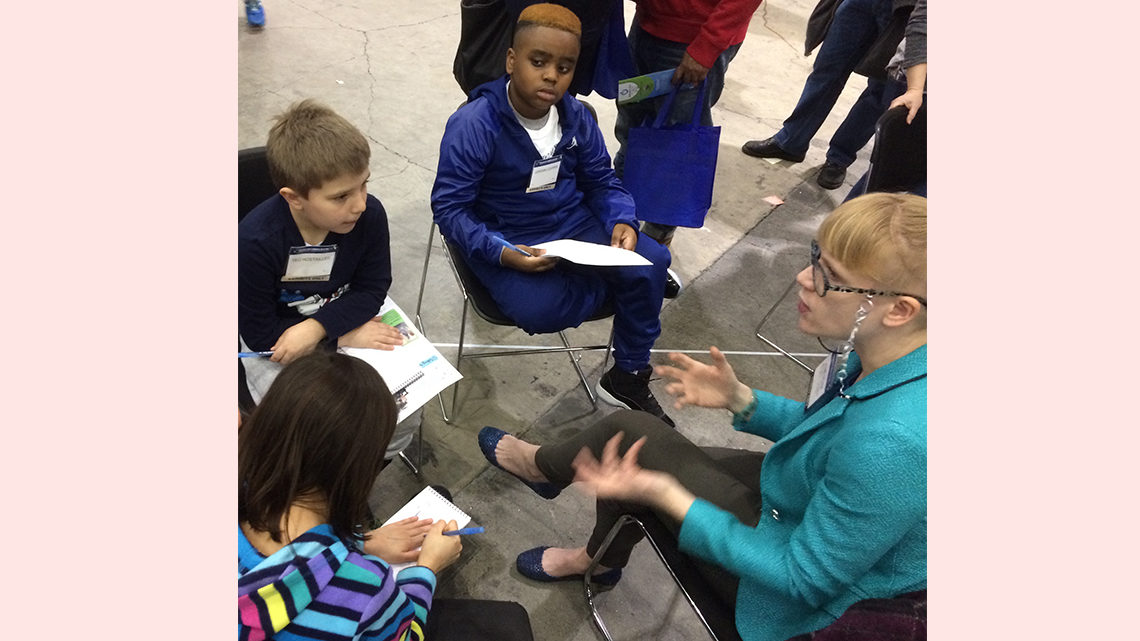

Kids who approached the booth would act as science journalists interviewing real-life scientists. Afterward, they would share what they learned.

Cutraro, who had been devising and planning the Science Storytellers program for over a year, would soon find out what happens when you ask a child, “Hey, do you want to interview a scientist?”

The clock struck 11 a.m., and the first Science Storytellers began.

Implementing an idea

Cutraro had noticed a growing conversation around public understanding of and engagement with science and decided it was time for some solutions.

The crux of the issue is that some scientists rely on one-way communication of knowledge, wrongly assuming that the uninformed are empty vessels waiting to be filled with knowledge. This method, called the deficit model of science communication, presumes that with this knowledge everyone will reach the same conclusions and make the same decisions.

In reality, research shows that transmitting scientific knowledge to the public is important, but actually shifting someone’s opinions requires engaging with them in a two-way dialogue and treating them as a whole, complicated person with knowledge, experiences and influences of their own.

Engagement requires more than just speaking; it requires listening.

What better way facilitate two-way dialogue than to pair scientists with people who are known for being especially open about their experiences, unafraid to ask questions and prone to saying unexpected things? (Kids!)

But would it work? Would kids be interested in being journalists? And would scientists be able to translate their research and experiences to a younger audience? As Cutraro discovered that day in Boston, yes.

One of the volunteers at that first Science Storytellers event was Brian Nosek, a psychologist at the University of Virginia who studies implicit bias—thoughts and feelings that exist outside of conscious awareness or conscious control, such as racial bias.

Nosek spoke to an 8- or 9-year-old boy who immediately made a connection between Nosek’s research and a story he knew. Cutraro, listening in, caught a bit of their conversation, which she and Nosek recall as going something like this:

Kid: What do you study?

Nosek: Well, I study why we sometimes treat people differently.

Kid: Do you mean like that lady on the train?

Nosek: Do you mean maybe a bus, not a train?

Kid: Yeah. It was a lady who was on a bus. Her name started with an R…

“This kid in Boston immediately made a connection with Rosa Parks,” Cutraro says. “For me, that was just a really profound moment. Kids do realize how relevant science is to society and times in our history.”

Kids control the conversation

Astrophysicist Augusto Carballido of Baylor University in Texas decided to volunteer for Science Storytellers at the following AAAS meeting, this one in Austin in 2018.

“I enjoy talking about science to nonscientists, but I had never talked with little kids,” Carballido says. “I thought Science Storytellers would be a good experience for me.”

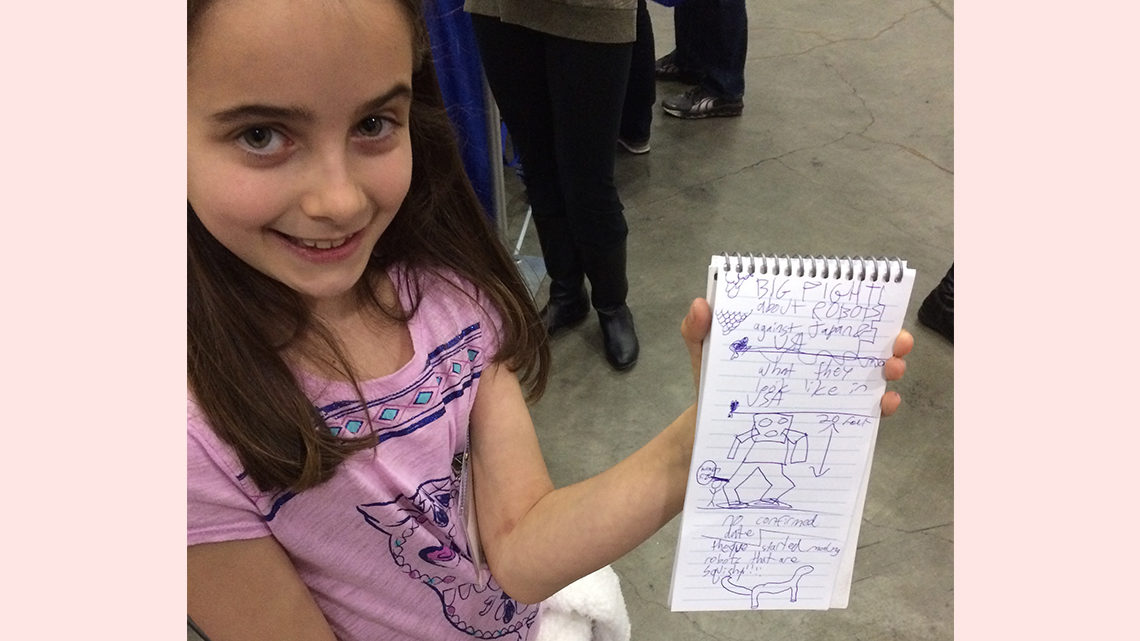

Before talking with scientists, kids participating in Science Storytellers receive a short handout describing what science journalists do, a reporter’s notebook to take notes on, and a list of suggested questions, such as, “What’s your work all about?” “How did you get interested in that?” and “Why does it matter?” After talking with scientists, kids fill out an open-ended grid called a “story starter” that helps them consider how they might describe what they learned in a story.

Carballido says he enjoyed the challenge of answering the kids’ questions.

“I really needed to figure out how to make my work relatable to others,” he says. “But it’s not in a way you might expect. No matter how intricate the problem, you can still address it, and the kids will be really interested. In fact, they are very persistent—they won’t let you go until you give a satisfactory answer.”

Carballido says kids asked about all sorts of topics, from planetary science and the Voyager probes to rocketry and the privatization of space travel.

And nothing was off-limits.

Kids were especially interested in scientists’ responses to a new question added to the suggested question list for the Austin meeting, he says: “Almost every kid asked me if I had ever been wrong about something.”

Scientists admitting to having been wrong makes them more relatable, Cutraro says. And scientists talking about how they learned from making mistakes shows kids a side of the scientific process they may not see in school.

Looking ahead

During the first Science Storytellers program, over 400 kids interviewed scientists. Since then, Cutraro estimates that number has swelled to over 1000 at AAAS the past three years.

Science Storytellers has grown beyond the AAAS meeting; the American Chemical Society hosted a Science Storytellers booth at its fall meeting in 2019 and saw nearly 400 visitors.

Cutraro hopes to continue to expand into other conferences and public-facing events.

“I’d love to move this program into classrooms and combine it with lessons about media literacy,” Cutraro says. “I’ve also thought about doing pop-ups at malls, libraries or farmers’ markets—anywhere people congregate.”

Cutraro says Science Storytellers has been more successful than she imagined. At the third AAAS meeting with a Science Storytellers booth, in 2019 in Washingon, DC, she even had some repeat visitors: A father-daughter duo who participated in Science Storytellers in Austin were back for more.

“In fact, this girl was so interested in science and asking scientists about what they do that she went to her father’s lab and interviewed all his graduate students,” Cutraro says.

So, what happens when you ask a child: “Hey, do you want to interview a scientist?” A whole lot of good.

If you will be in Seattle during the 2020 AAAS meeting and are interested in participating in Science Storytellers as a scientist or a science writer aide, please contact Jennifer Cutraro at jenny@sciencestorytellers.org. If you are interested in attending Family Science Days, visit the Sheraton Grand on Saturday, February 15, or Sunday, February 16, between 11 a.m. and 4 p.m.