Adam Nadel first learned about Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in the 1980s. He was a student at the University of Chicago, taking photos for the university newspaper. In 2018, more than three decades later, he arrived back in the Chicago area with his camera to serve as Fermilab’s new artist in residence.

Over the course of his career, Nadel has migrated from photojournalism for media toward photography for exhibits such as the one still open for the next couple of weeks at Fermilab.

Before arriving at the lab, he completed a project, supported by the National Science Foundation, on the Florida Everglades ecosystems and the people who care for them. The result was a powerful exhibit called “Getting the Water Right.” For Fermilab, Nadel proposed a project to showcase “people connecting and networking, and their relationship to that place.”

He visited the lab four times. While collecting the photographs to fulfill the promise of his original proposal, Nadel found himself pulled into the science as well.

“What became real to me,” Nadel says, “is both how small the things that are being investigated are—in terms of weight, size, charge, etc.—and the incredibly short duration of time they are being measured for. And it became immediately obvious there was just no way I was going to be able to artistically wrestle with those things with a still camera.”

So Nadel branched out.

Inside an accelerator, subatomic particles are accelerated to immense energies before colliding with other particles or a stationary block of material. These collisions create new particles with their own energies.

Nadel wondered how an electron beam would interact with sensitive photographic paper. With the help of Fermilab physicists Thomas Kroc and Michael Geelhoed at the lab’s Illinois Accelerator Research Center, Nadel decided to find out.

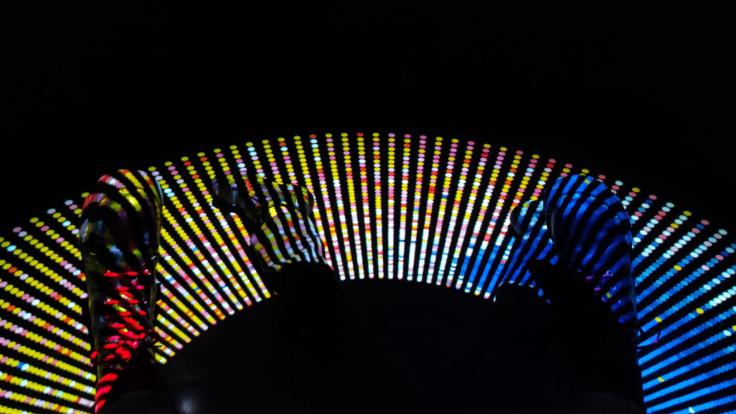

Bombarding photographic paper with electrons provided a compelling visual for the energy levels of the beam, making visible the shape and intensity of it. Nadel experimented with how best to show that energy by changing the proximity and angle of the paper, sometimes with surprising results. “You don’t want to fight the current, so to speak,” Nadel says. “It was a question of figuring out what was happening and why, and then using it to an aesthetic advantage.”

Nadel also explored how to make data collected by particle detectors accessible to human senses. He decided to use data from MicroBooNE, an experiment at Fermilab that records neutrino interactions using a large chamber lined with delicate wires and filled with 170 tons of liquid argon. Nadel created a simple formula to transcribe data recorded at 3-microsecond intervals into a 265-note score.

He wrote the music for two pianos and a cello. The first piano plays the unprocessed, messy data signal; the second plays the same signal, cleaned up, without the notes representing the background noise that can be caused by random events such as cosmic rays entering the detector; and the cellist plays the signal after it has been processed through a computer algorithm to highlight the path of a neutrino through the detector.

“It’s a conceptual approach, that allows any composer to create a musical score from any MicroBooNE data set,” Nadel says.

At the end of his last visit, Nadel accessed another data set: photographs of the paths of bubbles that particles left in an old-fashioned bit of technology called a bubble chamber.

Nadel wanted to explore the importance of this data and what purpose, if any, it might serve once an experiment is complete. Taking old bubble chamber negatives from Fermilab and Brookhaven National Laboratory, Nadel created new pieces by subtracting varying amounts of the data from the original images. In this manner, he explored each negative as a “piece of artistic data.”

One of the most surprising things he found, Nadel says, was how little the physical records themselves seemed to matter compared to the findings they were used to make.

“It made me question what I thought was important about an experiment,” he says. “I am very interested in the physical evidence generated during scientific investigation but for most scientists, it’s the discovery, the knowledge.”

Nadel is still grappling with the challenge of combining art and science. He sees his attempts as their own kind of experimental process.

With the work he made at Fermilab, Nadel wanted to put the viewer in the shoes of the experimentalist as well. “I wanted people, especially people at such a curiosity-driven place, to figure it out the same way I tried to figure out high-energy physics,” Nadel says.

“I provided viewers with visual [and audio] phenomena that they could hopefully apply a scientific method to try and figure out.”

Editor’s note: The application deadline for the 2020 Fermilab artist-in-residence program is September 1.