In the beginning, there is mud. And dust. We zip up our construction-site uniforms and decide what equipment we’ll take down with us. One elevator ride later, and we find ourselves 80 meters underground in a dimly lit tunnel undergoing a noisy excavation.

It’s August 2019, and I’m a photographer employed by CERN to create audiovisual content for CERN’s internal and external communication. Today a colleague and I are photographing the ongoing civil engineering for new passages, caverns and shafts that will enlarge CERN’s subterranean accelerator complex. When completed, they will house the powering, protection and cryogenic systems for the High-Luminosity LHC. These upgrades will increase the collision rate by a factor of five beyond the LHC’s design value and enable the experiments to search for new physics and phenomena that were previously out of reach.

A security officer guides us, making sure we stay out of the way of the heavy machinery while he shows us his favorite spots. The lighting is dim, which makes navigating the rocky and uneven pathway even more treacherous.

Our mission is to collect photos and video footage that both convey the feel of the place and document the action. In just a short time, with limited recording gear and the addition of bulky gloves, boots, masks and protective glasses, we rush to set up our shots.

Two things stand out: The scale of the place, and how rough an area it is. This, to a photographer, is a sign that it is time to break out the wide-angle lenses and get right up close to the workers. We want to create an immersive feeling for the viewer, a sense that they are right there with us taking in the entire scene.

Before coming to CERN in winter 2019, I primarily focused on wildlife photography and filmmaking. Working at CERN is unlike anything I’ve done before. I often say shooting the CERN caverns is where a top photographer can really make their mark. You are faced with huge structures but very little room to maneuver. It’s dark, so you need to hold for long exposures. But there are also lots of people and machines moving at all times. To balance all these factors at once is a real test of your skills.

Toward the end of 2019, the workers break through the wall and connect the new tunnel to the one that holds the LHC. Project leaders and the Director General of CERN hold a ceremony to commemorate the moment. The heads of CERN dress in work suits and descend the shaky metallic steps to pose for a photo and sit for a short interview under bright lights we set up for the occasion. It feels almost like being in a photo studio 100 meters underground.

In May 2021—18 months after the subterranean photoshoot—we return to the HL-LHC tunnels. The crews have been working 24/7 to get the tunnel construction completed before the LHC restart in Spring 2022. We are told that dust is no longer the issue, but vertigo might be. The temporary elevator is being replaced, so our way down is essentially a large bucket suspended by a rope. No room for unsteady nerves on this site!

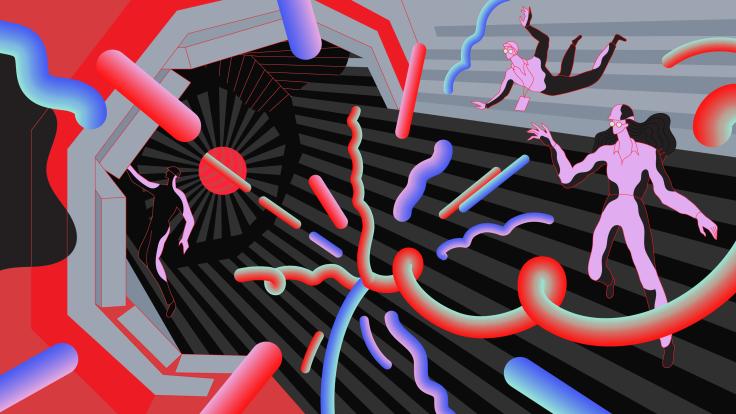

When we reach the bottom, the tunnel is radically different. We find ourselves in a clean, white entrance hall, with our path illuminated at regular intervals by elegant blue lights.

The challenge is now less technically extreme. Creatively, however, this is a whole new game. We still have the heavy machinery and workers in high-vis uniforms. But otherwise, the surroundings are pure science fiction. We respond with a change in style, paying attention to symmetry, proportions and structure to convey the modern, elegant environment.

It is a photographer’s duty to be adaptable and quick to come up with new ideas when documenting, and CERN’s ever-changing environments certainly test those skills. Conditions and constraints ultimately bring out creativity. It is remarkable to me to look back and see not only the evolution the location but also of my own perspective.