The crowd wound out the door at Brookhaven National Laboratory’s open house on October 18, 1958. Visitors lined up for an interactive exhibit, designed by William A. Higinbotham, a nuclear physicist who led the lab’s Instrumentation Division.

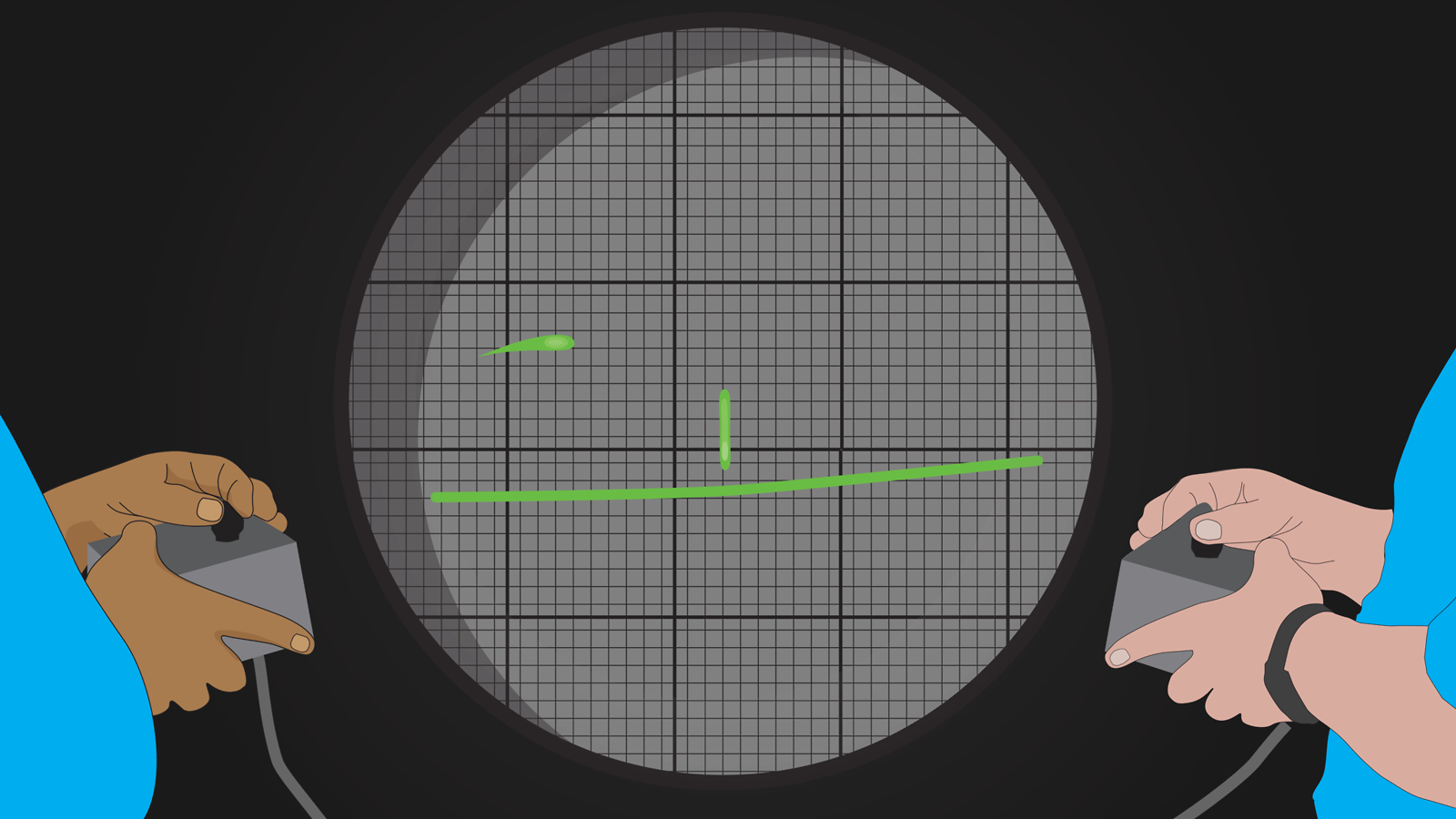

On a small, round monochrome screen similar to those used in early radar displays, a couple of green-lit lines and a streaking green dot had captured their attention.

It was a tennis simulation game that enabled two people, each holding a corded metal box, to press a button to simulate swatting the dot, or “ball,” back and forth on the 5-inch screen with unseen rackets, and to control the angle of each racket by turning a dial on the handheld box. A line at the bottom of the screen represented the surface of the court and a shorter line in the middle of the screen represented a net.

The button on each controller triggered a loud “click” in the device’s electrical switches, and the onscreen dot sailed in a new direction, arcing in simulated gravity and bouncing on the other side of the net.

“It had all the trappings of modern video games,” says Raiford Guins, associate professor of culture and technology at Stony Brook University, who this year released a documentary about the game, one of the world’s earliest electronic games. “It’s a simulation, it’s interactive, it’s designed for two people to play, you hold the controllers in your hand. Higinbotham wanted to entertain visitors. What is really significant about his contribution is that he brought computer gaming to the public.” Most other early electronic games were enjoyed primarily by select groups of researchers and technologists at universities and research centers, Guins says.

Higinbotham’s game, which was physically built and debugged by Brookhaven’s Robert V. Dvorak, with help from David Potter, predated the wildly successful “Pong” arcade game by more than a decade. It is actually cited by some sources as the world’s first video game.

It was made possible by an analog computer, likely originally used to solve equations related to nuclear and particle physics experiments, connected to hundreds of pounds of vacuum tubes, relays, transistors and other circuitry via a complex weave of wires dubbed a “rat’s nest” by its creators.

Peter Takacs, a Brookhaven physicist who has worked on recreations of the game based on Higinbotham’s technical drawings, says that a key innovation in the original game was a fast-switching circuit that used newly available transistors. That circuit refreshed the display of the ball, net and court at the then-“blazing fast” rate of 36 times per second.

After the game was shown at two consecutive Brookhaven open house events, it was disassembled and its components went to other uses.

Higinbotham, who died in 1994, was a Manhattan Project scientist who after World War II served as a leading advocate for the nonproliferation of nuclear weapons. He drew from his previous work on radar systems and electronics in laying out the schematic for the game, which became known as “Tennis for Two.”

Higinbotham, who considered the game a “minor accomplishment” compared with his many patents for radar displays and other technologies, wrote that the game was intended to convey the message that scientific endeavors have relevance for society.

“It was a fresh spin on big science: Science can be friendly, science can be fun,” says Guins. “What better way to do that than with a game?”