As Larry Lee walked around Slovakia’s largest annual music festival in July after playing his set, he got the typical rock star treatment. Fans recognized him in the crowd, approaching him to tell him how much they enjoyed what they’d heard. A few even said that he was their favorite performance of the entire Pohoda Festival—and its line-up included The Roots.

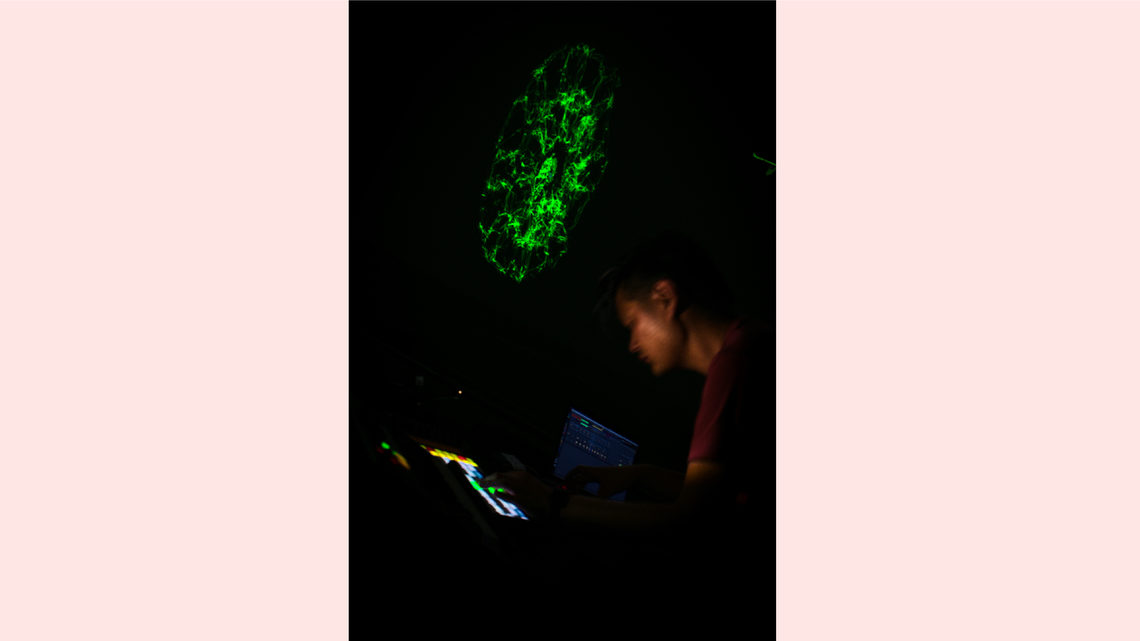

For Lee, though, this wasn’t typical. Lee isn’t a headlining musician. He’s a physicist on CERN’s ATLAS experiment, who’s used his musical training and an interest in collider machinery to create a new instrument of sorts. Using a piece of standard lab equipment, Lee has created a science-inspired, electronic music-backed light show. And Pohoda was his public debut.

“This was a performance where I’m the only person up there, controlling all the sound, and that was new and exciting for me,” Lee says. “But then doing this kind of strange science music was even weirder. I go back and I look at pictures of the audience during that time, and they’re glued to the stage.”

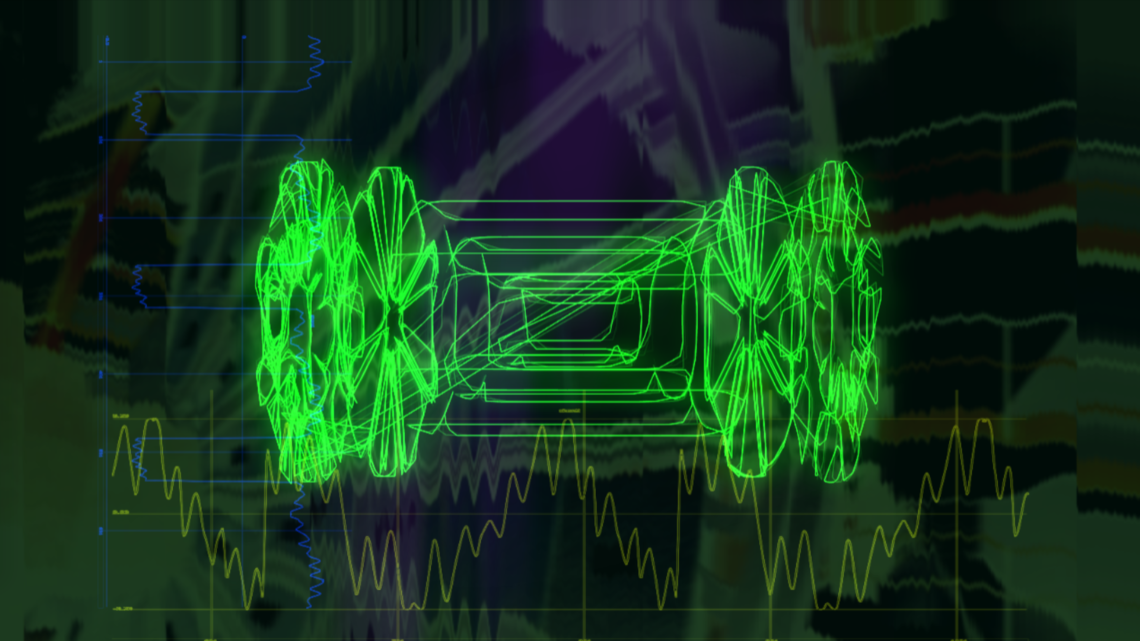

Lee first got the idea for the music after seeing a pair of musicians on YouTube creating sounds for a common physics instrument called an oscilloscope, which is used for measuring voltages. Oscilloscopes can trace changes in voltage over time, with the results appearing as visual readouts written in green light on a black screen.

Physicists frequently use oscilloscopes to compare how two different voltages are changing over time, forming figures known as Lissajous patterns from signals like sound waves. The patterns can then be played back through software to hear what sounds they’d correspond to.

Lee has played the saxophone since he was a kid, later picking up bass and piano, so the concept of using physics equipment to make music immediately clicked.

“As a musician I just really wanted to play with it from a creative point of view,” Lee says. “Within a couple hours I realized this is actually perfect for science outreach, because it’s the kind of equipment and signal analysis stuff that we do every day.”

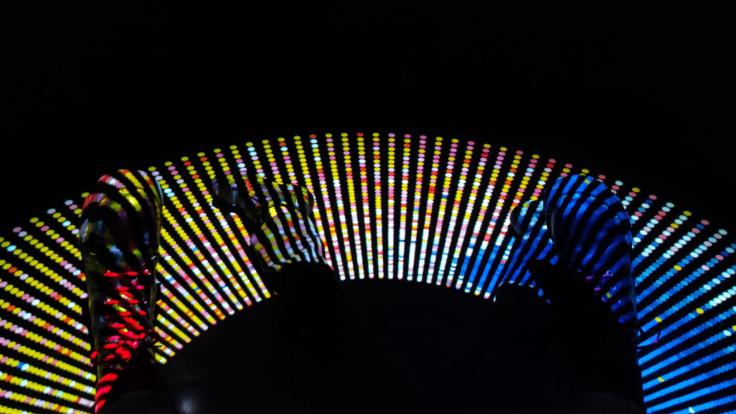

Lee uses the physical structures of the LHC as his visual input. He creates 3D models of the experiments and then feeds them back to the oscilloscope. The shape of the picture defines the timbre, or tone, of the sound, while the rate at which the picture is drawn defines the pitch.

“Each shape that I have corresponds to a timbre just in the same way a saxophone sounds different from a piano,” Lee says. “So I have all of these distinct instruments, one with some portion of our detector, another with the LHC, and I can write music for this orchestra of weird instruments I have.”

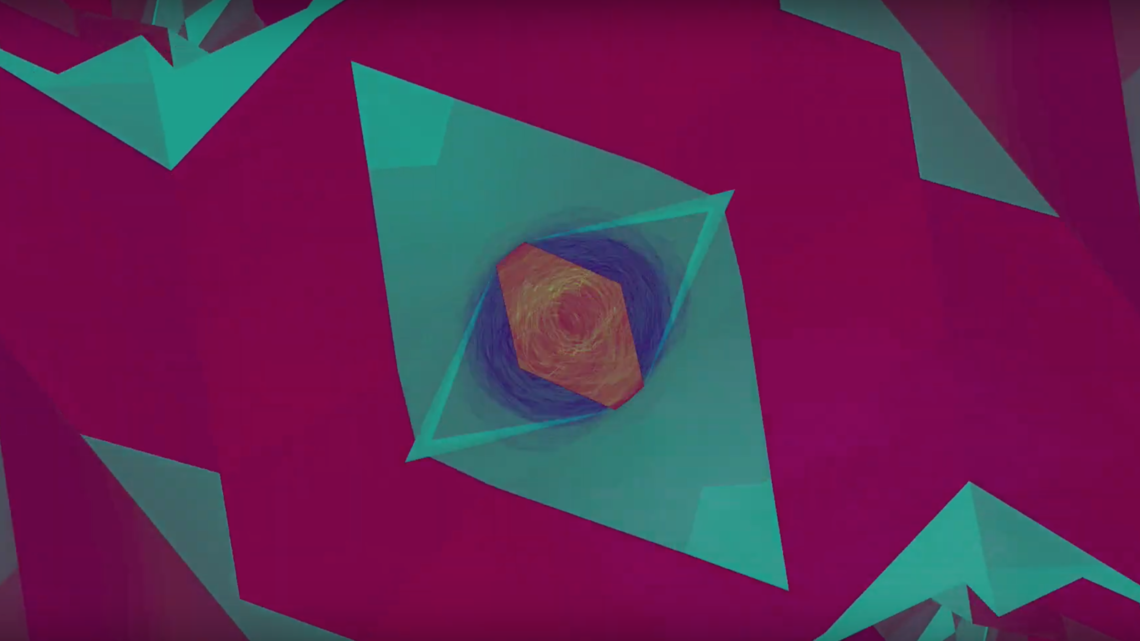

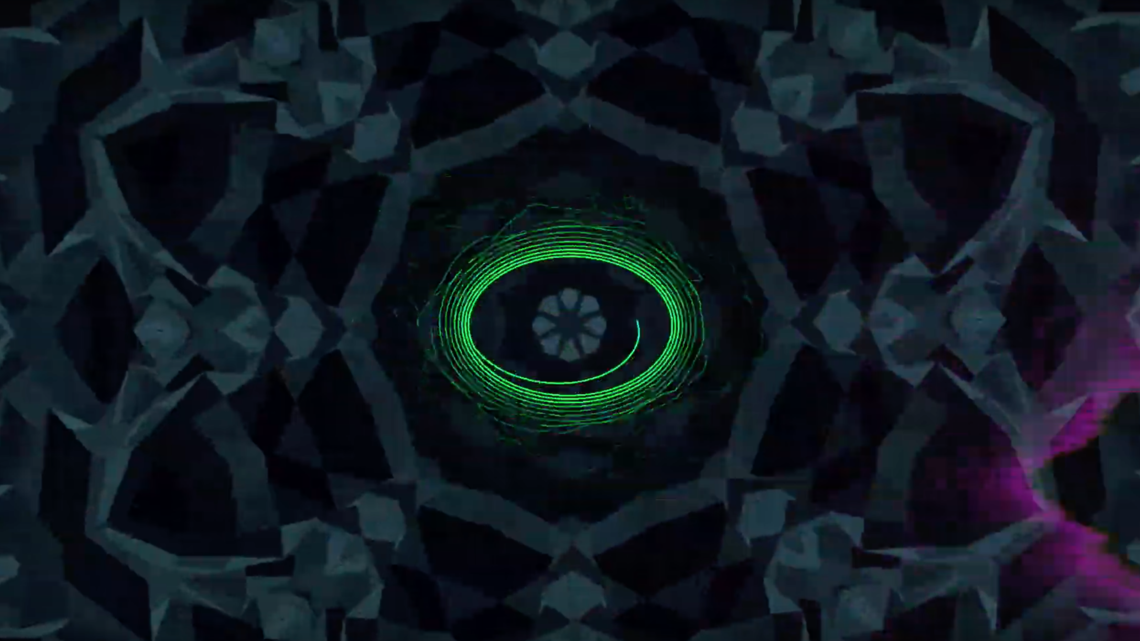

The resulting music sounds not unlike popular electronica—it’s easy to see how it would be at home at a music festival. One Pohoda attendee commented on Facebook that the show was “pure joy to listen and watch the visuals,” referring to the neon projections of the accelerator models that accompany the music.

Lee has dubbed the project ColliderScope.

While Lee focuses on the technical and musical aspects, his partner, Tova Holmes, has helped shape it into a science outreach project.

Holmes is also a physicist on the ATLAS experiment interested in compelling ways to communicate science to the public. That interest was sparked as an undergrad when she found that talking about exoplanet research grabbed the attention of a fourth-grade class she was teaching.

“It was the most magical thing,” Holmes says. “They were so excited, and all of a sudden they were completely engaged.

“It’s easy with exoplanets, but I think you can do this with a lot of things if you figure out how to present it right. I really love trying to see if you can turn any other science into exoplanets.”

Holmes recently co-created and hosted a podcast called In Particular, which explored both physics and the lives and perspectives of the researchers behind it. Lee worked on sound and music for In Particular, along with helping with other projects of Holmes’. So when Lee began working on ColliderScope, Holmes was a natural collaborator.

One of their first problems to solve was philosophical: How much science does a science outreach project need to teach?

“A big thing we talked about is whether your goal is for people to learn details, or to learn excitement about an idea,” Holmes says. “We try to balance those things, because fundamentally his thing is music, and it should be enjoyed.”

Both Lee and Holmes gravitated toward the idea that ColliderScope could get people excited about physics, even if they didn’t necessarily understand the details.

Lee made a video as part of the project, which caught the attention of Connie Potter, who organizes special events and conferences for CERN. Potter had organized a science pavilion at Pohoda and thought ColliderScope would be a natural fit.

Since Lee’s performance in July, he’s presented the project at the American Physical Society’s meeting in Boston, the International Conference on New Frontiers in Physics in Greece, and CERN Open Days, during which the European research center opened its doors to the public for two days. CERN physicist Andreas Hoecker called the Open Days performance “beautiful and much praised,” while University of Geneva physicist Anna Sfyrla said ColliderScope is a “fascinating project that explains the physics of music in a uniquely artistic way.”

Lee and Holmes hope to expand the project by making it accessible for more institutions. The process works best on older (and thus cheaper) oscilloscopes, Lee says, providing a nearly free opportunity for science outreach. Lee hopes physicists will use the files he makes available on ColliderScope’s website to turn unused, outdated equipment into their own unique displays.

For both Lee and Holmes, ColliderScope continues to challenge their ideas of successful science outreach—what forms it can take, who can access it, and what the results should be.

“I have no idea how much [the festival audience] understood about the underlying thing, but something I really came to realize is I don’t care,” Lee says. “It’d be really great if they did, but the fact that they had an amazing time on their own turf, enjoying music on its own, knowing there’s some kind of science angle to it—that, to me, is a really important direction for outreach.”