Not long after physicists on experiments at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN laboratory discovered the Higgs boson, CERN Director-General Rolf Heuer was asked, “What’s next?” One of the top priorities he named: figuring out dark matter.

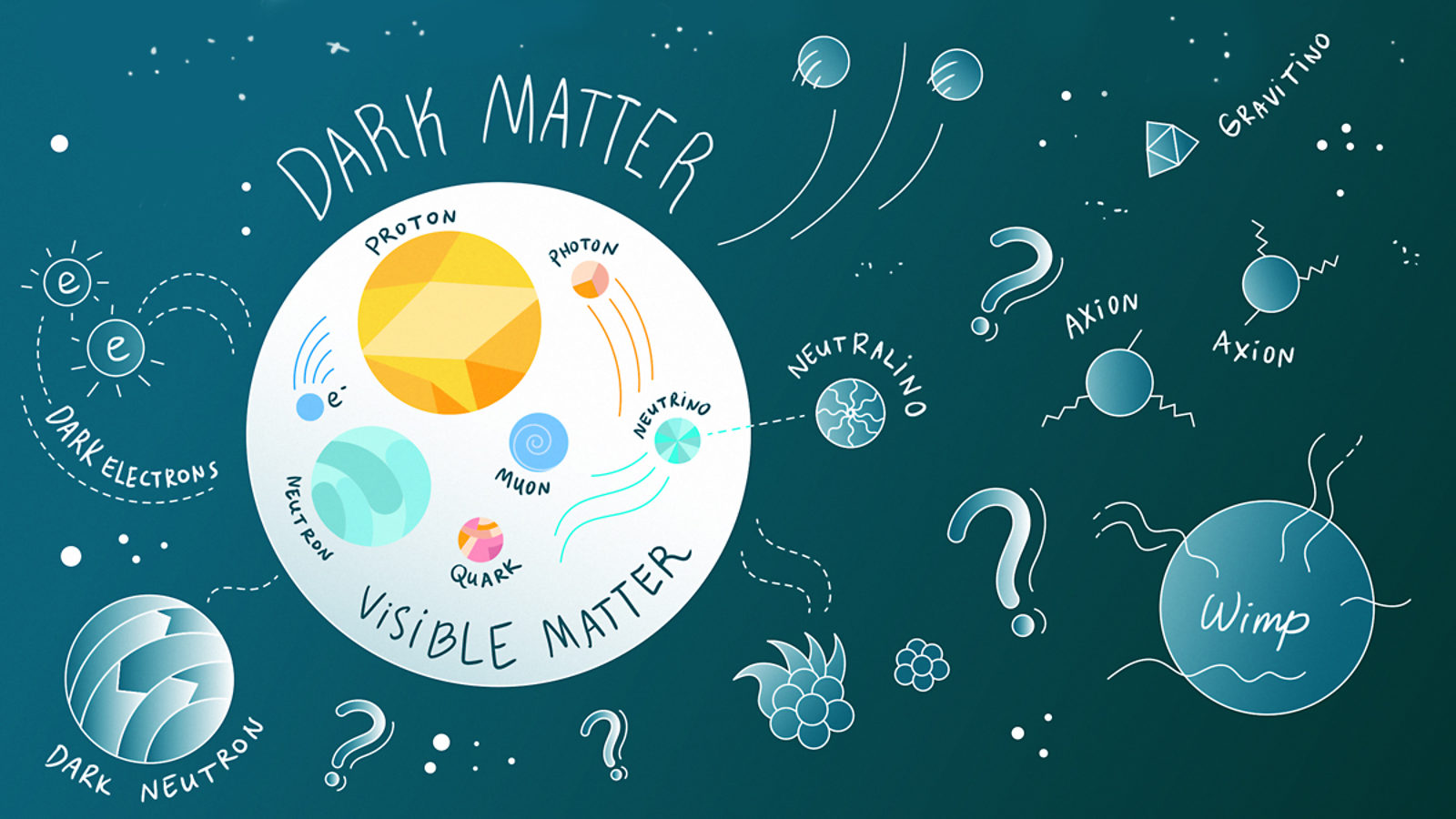

Dark matter is five times more prevalent than ordinary matter. It seems to exist in clumps around the universe, forming a kind of scaffolding on which visible matter coalesces into galaxies. The nature of dark matter is unknown, but physicists have suggested that it, like visible matter, is made up of particles.

Dark matter shows up periodically in the media, often when an experiment has spotted a potential sign of it. But we are still waiting for that Nobel-Prize-triggering moment when scientists know they finally have it.

Here are four facts to get you up to speed on one of the most exciting topics in particle physics:

1. We have already discovered dark matter

At this moment, several experiments are on the hunt for dark matter. But scientists actually discovered its existence decades ago.

In the 1930s, astrophysicist Fritz Zwicky was observing the rotations of the galaxies that form the Coma cluster, a group of more than 1000 galaxies located more than 300 million light years from Earth. He estimated the mass of these galaxies, based on the light they emitted. He was surprised to find that, if this estimate were correct, at the speed at which the galaxies were moving, they should have flown apart. In fact, the cluster needed at least 400 times the mass he had calculated to hold itself together. Something mysterious seemed to have its finger on the scale; an unseen “dark” matter seemed to be adding to the mass of the galaxies.

The idea of dark matter was largely ignored until the 1970s, when astronomer Vera Rubin saw something that gave her the same thought. She was studying the velocity of stars moving around the center of the neighboring Andromeda galaxy. She anticipated that the stars at the edge of the galaxy would move more slowly than those at its axis because the stars closest to the bright—and therefore massive—cluster of stars in the center would feel the most gravitational pull. However, she found that stars on the margins of the galaxy moved just as quickly as those in the middle. This would make sense, she thought, if the disc of visible stars were surrounded by an even larger halo made of something she couldn’t see: something like dark matter.

Other astronomical observations have since confirmed that something strange is going on with the way galaxies and light move through space. It’s possible that our confusion stems from a flaw in our understanding of gravity—Rubin herself said she favors this idea. However, if it’s true that dark matter exists, we’ve already seen its effects.

2. We have possibly already observed dark matter

Several experiments are searching for dark matter, and some of them may have even already found it. The problem is that no experiment has been able to make that claim with enough confidence to convince the wider scientific community—either due to statistics or an inability to rule out alternative possible explanations. And no two claims have lined up quite convincingly enough for scientists to declare any result confirmed.

In 1998 scientists on the DAMA experiment, a dark matter detector buried in Italy’s Gran Sasso mountain, saw a promising pattern in their data. The rate at which the experiment detected hits from possible dark matter particles changed over the course of the year—climbing to its peak in June and dipping to its nadir in December.

This was exactly what DAMA scientists were looking for. If our galaxy is surrounded by a dark matter halo, the Earth is constantly moving through that halo as it orbits the sun—and the sun is constantly moving through the dark matter as it orbits the center of the Milky Way. During half of the year, the Earth is moving in the same direction as the sun. During the other half, it is moving in the opposite direction. When the Earth and the sun are moving in tandem, their combined velocity through the dark matter halo is faster than the Earth’s velocity when it and the sun are at odds. DAMA’s results seemed to reveal that the Earth really was moving through a dark matter halo.

However, some loopholes exist; the particles the DAMA detector has been seeing could be something other than dark matter, something else the Earth and sun are constantly moving through. Or something else could be changing in the nearby environment. The DAMA experiment, now called DAMA/LIBRA, has continued to see this annual modulation, but the results are not conclusive enough for most scientists to consider it a dark-matter discovery.

It’s going to be difficult for any one experiment to convince scientists that they’ve found dark matter. It might be that people will come around only when several experiments start to see the same thing. But that will depend on what they find, says theorist Neal Weiner, director of the Center for Cosmology and Particle Physics at New York University. Dark matter could turn out to be something stranger or more complicated than we expect.

“If dark matter turns out to be something totally garden-variety, then maybe it will only take one experiment for people to be excited about it—and two for people to be borderline convinced,” he says. “But if something unexpected shows up, it might take more than that to persuade people.”

In 2008 the space-based PAMELA experiment detected an excess of positrons—a possible result of dark matter particles colliding and annihilating one another. In 2013 the AMS-02 experiment, attached to the International Space Station, found the same result with even more certainty. But scientists remain unconvinced, arguing that the positrons could also come from pulsars.

Underground experiments—including CoGeNT, XENON, CRESST, CDMS and LUX—have gone back and forth supporting and disclaiming possible dark matter sightings. It seems we will need to wait until the upcoming generation of dark matter experiments is complete to get a clearer picture.

3. We don’t know what dark matter is like; there could be several kinds making up a whole “dark sector”

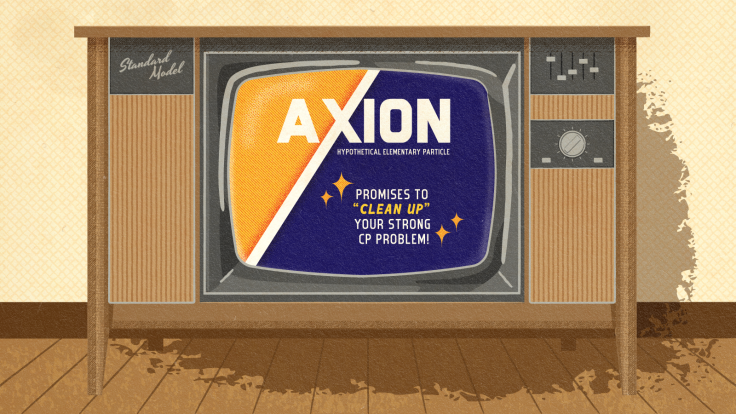

Scientists have come up with several models for what dark matter might be like. The current leading candidate is called a WIMP, a Weakly Interacting Massive Particle. Other possibilities include particles conveniently already predicted in models of supersymmetry, a theory that adds a new fundamental particle to correspond with each one we already know. Groups of scientists are also searching for dark-matter particles called axions.

But there’s no reason there should be only one type of dark matter particle. Visible matter, the quarks and gluons and electrons that make up all of us and everything we can see, along with an entire zoo of fundamental particles and forces including photons, neutrinos and Higgs bosons, makes up just 5 percent of the universe. The rest is dark matter—which makes up about 23 percent—and dark energy, a whole other story—which claims the remaining 72 percent.

As Weiner puts it: Imagine a scientist in the dark-matter world trying to understand visible matter. Visible matter composes such a tiny fraction of what's out there; what dark-matter scientist would guess at its variety? The world we know is so diverse; why would dark matter be so simple? Scientists have wondered whether dark particles could combine into dark atoms that would interact through dark electromagnetism. Could dark chemistry be next? Scientists have begun to look for light dark-matter particles predicted in models of the “dark sector.”

4. Chances are good that we’ll observe dark matter in the next 5 to 10 years—but we may never see it at all

These are heady times for a scientist searching for dark matter. With a number of different experimental ideas scheduled to come to fruition in the coming years, many predict that dark matter will be in our grasp within a decade.

“Really one of the exciting things is all of these techniques are coming to maturity at the same time,” says theorist Tim Tait of the University of California, Irvine. “It’s a great opportunity to play them against each other and see what’s going on.”

Scientists could find dark matter in a few different ways.

First, they could detect it directly. Direct detection involves waiting patiently with a big, sensitive experiment in a quiet, underground laboratory, as free as possible from potential interference from other particles. In the next few years, scientists will narrow down their current list of detector technologies to focus their resources on building the biggest, most sensitive generation of experiments yet.

The second way to find dark matter is to observe it indirectly—by seeking out the effects of dark matter with space-based experiments. Updates from current experiments on satellites and the International Space Station will give scientists more data to help them determine the meaning of the possible dark-matter effects they have been seeing.

The third way to find dark matter is to produce it in an accelerator such as the Large Hadron Collider. It is possible that, when two particle beams collide in the LHC, their energy will convert into mass in the form of dark matter. The LHC is currently shut down for maintenance and upgrades, but when it restarts in 2015, it will reach almost double its previous energy, opening the door for it to make particles it has never made before.

Once scientists find dark matter using one method, they’ll be able to focus their efforts, Tait says. Once we know more about its properties, “that’ll really energize all of this activity,” he says. “Right now we’re in a dark room, fumbling around. Once you know where the thing you’re looking for is, you can study it a lot more carefully.”

But it is also possible that dark matter is out of our reach, simply too elusive to detect or produce. If scientists don’t see dark matter in the next 10 years, they might need to find a new way to look for it. Or they might need to reconsider what they know about gravity.