|

|

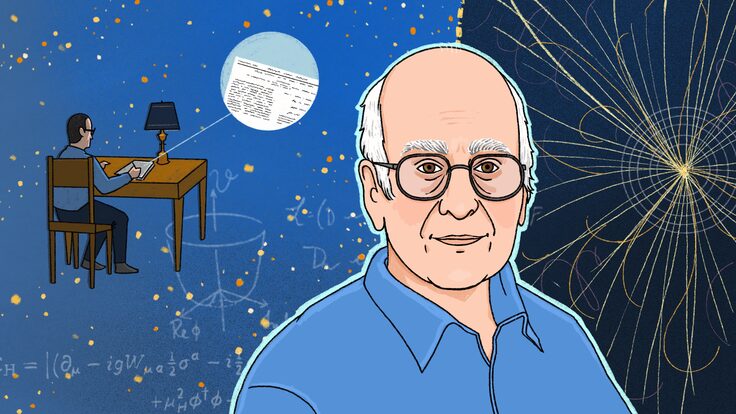

| Photos: Aristeidis Karalis |

Cordless juice

Peter Fisher was in the audience when Marin Soljacic, a fellow physicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, gave a lunchtime talk about a technology that could transform consumer electronics.

“It was just a theory talk,” Fisher says, “and I wasn’t really paying attention. But at the end he started talking about what it might look like. I thought, ‘We could build that, easily.’”

That’s how Fisher, a particle physicist whose normal preoccupations run to dark matter, neutrino oscillations, and cosmic rays, became part of a team that demonstrated how to transmit electrical power without wires.

Their paper, published June 7 in Science Express, made quite a splash. The initial experiments successfully lit up a 60-watt bulb from a power source more than two meters away (see photos). But the potential applications are much broader: Smaller, lighter laptops that never run out of juice. Cell phones that start charging the moment you walk into a room. Cordless table lamps: Plop them anywhere!

“The idea is to get rid of cables and batteries,” Fisher says.

“We found this undergraduate named Robert Moffatt who did most of the work” with the aid of graduate students Aristeidis Karalis and Andre Kurs, he says. “ Once we got going it took maybe three months to build the thing. It’s not at all sophisticated; it’s something almost anyone who had an interest in experimental physics could think up and execute.”

In fact, the idea dates back to the late 1800s, when Nikola Tesla experimented with the wireless transmission of electrical power.

Here’s how the team’s method —called WiTricity—would work:

Put a loop of coiled wire up near the ceiling and run an oscillating current through it to create a magnetic field. This is your power source for everything in the room.

The magnetic field must oscillate at exactly the right frequency to resonate with similar coils in your computer and other gadgets. It pushes the electrons within the coiled wire back and forth, as if pushing a kid on a swing, creating a current that can be used to do work.

Fisher says it’s not the first time he has ventured out of basic research to tackle something practical. “About 10 years ago we had a scheme for tracking nuclear submarines that we talked to the Navy about. That didn’t go anywhere,” he says. “There was a guy who wanted to inflate tires with vinegar and baking soda. He paid me about $5000 to convince him it wasn’t possible.”

But now, he says, it looks like he’s found a project that could fly.

“We don’t have a business model yet,” Fisher says. “But just look at WiFi. If you can build something where the transmitter is $200, and the receivers can fit into existing equipment and cost $30, people would buy them.”

Glennda Chui

Click here to download the pdf version of this article.