Underground and closed off from visitors, experiments in particle physics often hide, rather than flaunt, the exotic and intricate machines that seem more at home in a science fiction blockbuster. No space shuttles, rockets or rovers wow visitors at today’s physics laboratories. The tried and true conduit from the underground to the outside world remains in most part the camera.

Polarized electron source, Bates Linear Accelerator Center, MIT, Massachusetts, 2007. Photo: Stanley Greenberg

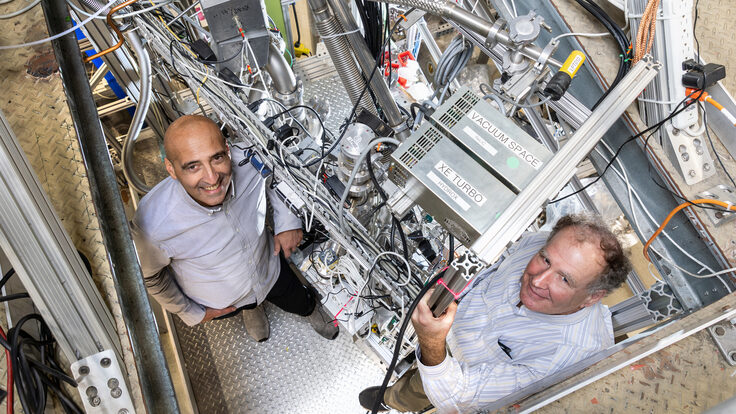

In his new book, “Time Machines,” New York-based photographer Stanley Greenberg immersed himself within physics machinery to capture the cannon-like CMS detector before installation at the LHC, the frigid lifelessness surrounding the ICECUBE Neutrino Observatory in Antarctica and the Frankenstein mystique of Fermilab’s Cockroft-Walton accelerator. Greenberg’s book assembles 80 rich, black-and-white photos that distill from the complex machines a space-age style and individual personalities – preserving a romanticism free of scientific overload.

“Their massive cement blocks, multi-story electronics, and miles of circumference dwarf their human makers as intestines of tubes and wires converge Leviathan-like into the ultimate probe of the tiniest and the most hidden secrets of the vast universe,” writes David Cassidy in his imaginative, yet informative, introduction to “Time Machines.”

In his previous works, Greenberg, who is no stranger to towering structures, delved into sub-city tunnels, toured waterfront shipyards and scaled the skeletons of burgeoning buildings. He then left his home in New York City on a five-year quest to photograph the infrastructure and equipment of the most advanced high-energy and nuclear physics laboratories.

“It’s an almost completely hidden kind of world,” Greenberg said. “That’s always been an attraction to me – the places people can’t go.”

Assuming access to laboratories to be a challenge, Greenberg instead discovered open doors and smiling scientists, who often invited him before he asked.

Drawn by sweeping patterns that slice across his lens and massive structures that hemorrhage off the pages of his book, Greenberg has, for the most part, let the reader’s mind simply admire the machinery and wander what roles these strange instruments would fill.

“There are parts you see that will hopefully become metaphors for the whole,” Greenberg said.

While the book does briefly explain the experiments in the introduction and appendix, this is not a science book – it is a celebration of science.

What’s left out of the book are hundreds of old negatives from an era when bubble chambers were ubiquitous in the field. Greenberg collected and borrowed these abstract portraits of particles in the hope of one day displaying them in a gallery.

The collection in this book is simply one selection of weird and complex experiments from across physics history. Yet each otherworldly machine by being framed within a photograph is frozen in its own unique and immutable time.

All travel for the book was funded by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, and the NSF Artists and Writers Program funded Greenberg’s trip to the South Pole.