Many movies use pseudoscience to explain the origins of their villains. A film released this weekend follows the same model, but its producers and stars all know better than to buy the nonsense: They’re PhD students and postdocs in particle physics.

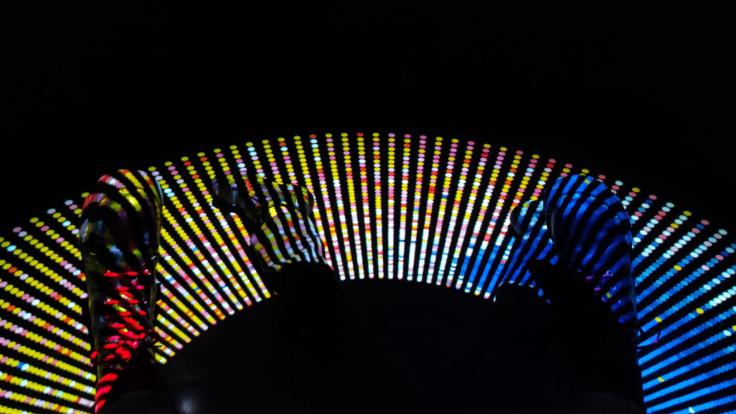

The zombie horror film Decay tells the story of an unlucky group of students who find themselves trapped in an underground control room after the Large Hadron Collider malfunctions and exposes a group of engineers to so-called Higgs radiation. The made-up phenomenon transforms them into flesh-hungry zombies. As the students attempt to escape through a maze of tunnels, they clash with the monsters and encounter clues as to what caused the disaster.

The film’s writer and director, Luke Thompson of the University of Manchester, strove to make the science outrageously implausible as a dig at popular Hollywood films with misguided science scenarios.

“Sometimes we had to fight hard to make sure everything was rubbish,” Thompson says. “Actors would say, ‘No, you can’t say that. It’s so wrong!’ But that’s exactly what we were going for."

Much of the action takes place in actual underground tunnels that link buildings at CERN. In reality, the tunnels do not lead to the LHC (nor are the control rooms located near the beamline underground), but their dodgy lighting, dark corners and dead ends did provide an ideal environment for a horror film. At least that’s what Thompson and a group of his friends thought when they first decided to make the film in 2010.

“The tunnels are horrifying,” says Burton DeWilde, who recently earned his PhD from Stony Brook University and who served as co-producer, director of photography and editor of the film. “On more than one occasion when I was down there alone planning out a shot, I would hear something and my skin would crawl.”

Associate producer, assistant director, University of Manchester student and “chief zombologist” Clara Nellist hopes that creepiness translates into the film. She also hopes viewers appreciate some of the subtle references included in the work for fellow zombie-film aficionados.

“I tried to push for as many zombie references as possible because I wanted to make a nod to the films that inspired us,” such as 28 Days Later and Shawn of the Dead, Nellist says.

Producing a film can itself be a full-time job, but so is working toward a PhD in physics. Most of the group members were students at the time of production. They set time aside one night a week and devoted every available Saturday for about 2.5 years to make the film.

“It was like a whole life for [nearly] three years,” says Zoë Hatherell, who plays the lead and who recently earned her PhD from Imperial College London. “There were tears, arguments, amazing joy and a lot of laughs. It was a fantastic experience, and the film is just one example of what you can achieve with people like that.”

The response to the film has been greater than anyone expected, says producer Michael Mazur, formerly a postdoc at the University of Bonn.

“We've been overwhelmed by the response," he says. "This is something we did for fun in our spare time. That so many people are excited by the film, and that they're enjoying it, is truly fantastic."

On Nov. 29, 500 people attended the film’s premiere at the University of Manchester. The YouTube trailer has nearly 150,000 views; the film’s Facebook page has over 1,600 likes; and the video is already accumulating tens of thousands of downloads and views on YouTube and Vimeo.

“The zombie film genre is really oversaturated at this point,” DeWilde says. “So it takes something special, something different to excite the internet.”

So far, Thompson says there are no plans for a sequel. However, he joked that he might reconsider if Fermilab were willing to sponsor the next one.