Natalie Harrison holds a CCD in a clean room at SiDet.

This story first appeared in Fermilab Today on October 25, 2010.

Many 16-year-olds learn important life skills at their first summer jobs – the value of a dollar or how to deal with the public. Natalie Harrison learned detector modeling, particle astrophysics and C++.

Harrison, now 17 and a senior, has spent the past two summers working 40 hours a week at Fermilab. She also works during the school year.

A student who regularly enrolls in courses several years above her grade level, Harrison exhausted the available math and science classes at Naperville North High School after her freshman year. She sent letters to every local scientist she knew in search of a way to continue her education.

“I contacted tons and tons of people,” she said. “Most of them never got back to me. At times I thought, ‘I’ll never get an internship. I’ll just work at the pool.’”

Harrison was saved from a summer of scooping chlorine when a Fermilab physicist invited her to work on a poster for the display area in the CDF detector hall at the Tevatron particle collider. The poster needed to contain only basic information for the general public, but Harrison combed scientific papers to learn as much as she could.

It was a habit she picked up as a 7th grader while attending Saturday Morning Physics lectures at Fermilab.

“As nerdy as it sounds, I would go home and go to the library and read until I understood what they were talking about,” Harrison said. “I thought it was fascinating that you could apply math to physics. This was way cooler than doing math contest problems.”

Fermilab scientists noticed her enthusiasm.

“She wants to know everything,” said Ben Kilminster, now Harrison’s supervisor. “The poster wasn’t challenging enough.”

Fermilab scientist Juan Estrada shows Natalie Harrison a CCD in a clean room at SiDet.

Kilminster asked Harrison if she would like to help with a new dark matter experiment called DAMIC.

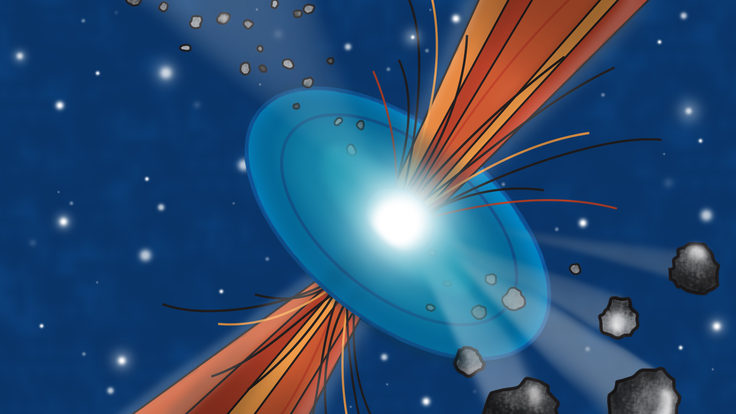

Fermilab physicist Juan Estrada spun off the DAMIC experiment from his work for building imaging devices for the Dark Energy Survey. The devices, called CCDs, take detailed photographs of the shape of the universe and search for signs of dark energy. Estrada realized he could use the same sensitive apparatus to search for dark matter particles.

Since Harrison began to work on the project, she has developed tools that the scientists use for quality analysis. She helped to study which configuration would work best for the next prototype detector and determined that a beam of neutrinos in the NuMI hall was affecting the detector’s background levels.

“She doesn’t require much supervision, just someone to point her in the right direction,” he said. “She’s doing the same things we have senior physics majors in college and graduate students do.”

But she’s still a high school student. Like other high schoolers, she’s busy running cross country, tutoring other students and applying to universities. She said she hopes to find time between all of that and her job at the laboratory for another typical high school experience: earning her driver’s license. That way, her mom won’t have to drive her to work.