When Evan Coleman was wrapping up his undergraduate studies in physics at Brown University, he wanted to find something special to give his mentor, Meenakshi Narain.

“How do you get a gift for someone who has defined your career?” Coleman says.

When he started at Brown, Coleman was undecided about whether to major in physics, engineering or computer science. At a math department event, he met one of Narain’s students, who recommended Coleman talk to her about a research position in her lab. He later discovered he was already good friends with Narain’s son.

“Given the serendipity of it all, I figured I’d better give physics research a try,” Coleman says.

In Narain’s lab, he analyzed data from the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) experiment at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN.

Narain has a history with particle collider experiments. In the early 1990s, she joined the DZero experiment at the Tevatron collider at the US Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. At the time, physicists had discovered five of the six quarks—only the heaviest, the top quark, remained hidden. Narain was a part of the group that, in 1995, finally found that last piece of the quark puzzle.

When Coleman joined Narain’s lab, she was focused on the top quark once again—this time, measuring its width with extreme precision.

“Meenakshi really taught me and mentored me from the ground up,” Coleman says. “Her mentorship really changed everything. The environment in her lab was super positive, and I felt like I had gained a second family.”

After graduating from Brown in August, Coleman began a doctoral program in physics at Stanford University, where he is a National Science Foundation graduate fellow.

Coleman discussed what to give Narain as a parting gift with his mom, Kate Mulligan. Mulligan, who is a graphic designer, says she loves textiles and thought a silk scarf depicting an equation would be the ideal gift.

Inspired, Coleman showed his mom sketches of Feynman diagrams. Named for their creator, physicist Richard Feynman, the diagrams tell a science story in symbols. Through lines and loops, they illustrate the often complicated transformations that occur when elementary particles interact.

“Mom picked up the Feynman diagrams pretty quickly,” Coleman says. They chose one that demonstrates the production and decay of the top quark.

“We were interested in making this very unique, and specific to Meenakshi,” Mulligan says. She knew a silk artist, Carol Baker, whose father happened to have been a physicist as well, and she commissioned Baker to create the piece.

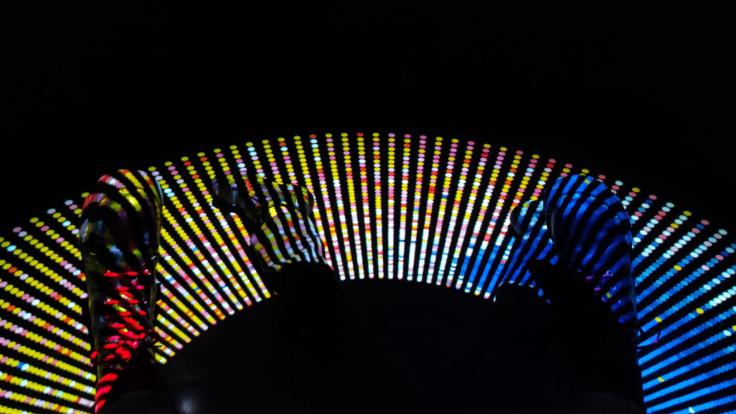

The scarf is over 5 feet long. Against its turbulent background of blues and purples, a quark and an antiquark smash into one another and fuse to form a gluon. The gluon spirals across the middle of the scarf before decaying into a top quark and an anti-top quark, which themselves deteriorate into pairs of W bosons and bottom quarks. Finally, the W bosons each decay into a lepton and a neutrino.

Narain says that she sees science-themed attire as a way to promote science and make it feel less exclusive.

“It’s a valuable outreach mechanism,” she says. “Science ‘fashion’ takes science to large audiences who are not necessarily science-minded.”

And the scarf is certainly unique—and specific to Narain in more than one way, she says. “The scarf captures my passions about promoting intersections between art and science.”