|

|

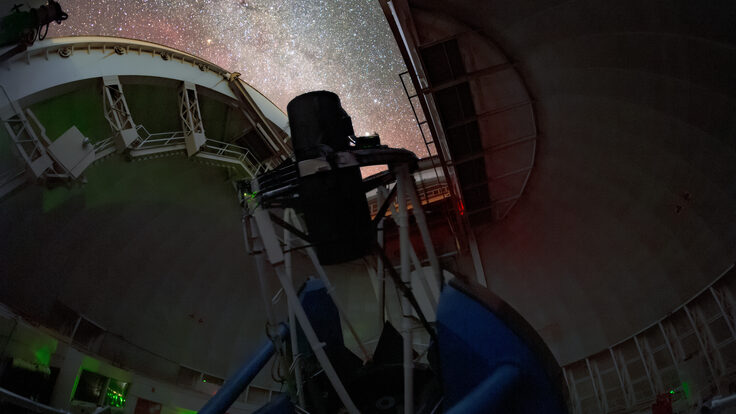

Photo: Reidar Hahn, Fermilab |

Diving for zebras

Ben Czaplewski lifts a 30-pound helmet onto his head and lowers himself into a manhole. He disappears without a splash.

Water is the lifeblood of Fermilab's Tevatron, the world's highest-energy particle accelerator. Its intake pipes suck 5000 gallons of water a minute into the accelerator rings, cooling superconducting magnets that direct beams of proton and antiproton particles hot enough to melt metal.

But that flow has slowed, blocked by invasive zebra mussels that build up like plaque in the arteries of a heart. Now, armed with hoses, scrapers, and chemicals, Czaplewski must root them out.

The cloudy pond water leaves Czaplewski working blind, pulling himself through intake pipes three feet in diameter, 75 feet long, and lined with zebra mussels.

“Your only eyes are these,” he says, fanning out his gloved fingers. Like a surgeon using a camera scope to find a blocked artery, he relies on his land crew to guide him with engineering blueprints and a two-way radio.

Czaplewski works for Lindahl Marine, which sends a crew of divers four or five times a year to clear out the pipes. The crew is accustomed to diving in places with limited to no visibility: steel mills, oil refineries, nuclear power plants, and sewage treatment plants. Still, a physics lab counts as unusual.

Diver Nate Lesley remembers a field trip to Fermilab as a schoolchild. “I definitely never imagined I'd be diving here,” he says.

Suddenly loud static crackles from the radio, followed by several thumps. With a splash of water, a hand reaches out of the access hole, clutching an injection line that is supposed to trickle a mussel-killing chemical into the pond. It is broken and caked with zebra mussels; now it will be replaced.

Stage one of the operation is complete.

Jennifer Lee Johnson

Click here to download the pdf version of this article.