The art of the unseen

by Ken Kingery

As technology evolves, posters are getting easier to produce and pass around. But it still takes skill and imagination to illustrate the abstract ideas of physics.

|

| Many thanks to the laboratories contributing posters for this article: Argonne National Laboratory, CERN, Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, Jefferson Lab, Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, and TRIUMF. |

They’d look right at home in a movie theater: A retro, hand-painted Godzilla stomps through blazing rubble amid swarms of airplanes. A woman throws her head back and screams as malevolent birds watch from a gnarled tree. A boxy cartoon robot casts an ominous shadow.

For all their B-movie flair, these posters go beyond mere entertainment. They advertise talks on serious scientific topics at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center in California. Godzilla represents political attacks on science; the screaming woman, the dangers of avian flu; and the robot, the long reach of advancing technologies.

“It’s a lot of fun,” says Terry Anderson, head graphic designer with SLAC’s InfoMedia Solutions group, whose posters have become a cherished part of lab culture. “I get to play Hollywood for a little while.”

Posters are a tradition in particle physics, a way of announcing conferences, workshops, and other events that bring the community together. Over the past 25 years they have evolved from pen-and-ink drawings, laboriously produced and printed, to eye-popping computer graphics that can be turned out in a matter of hours. Once available only through the mail, posters can now be downloaded from the Internet.

The role of graphic artists at high-energy physics labs has also changed. Two decades ago, they might have spent 90 percent of their time creating charts and figures for scientific papers and conference presentations. Now that scientists can do much of that work themselves with the aid of graphics software, artists are free to pour their energies into other areas, such as interpreting physics for the public.

“People in the world of physics are used to the blurred boundaries that separate what you can actually see and what you can envision in your mind’s eye,” Anderson says. “The result is a large range of possibilities that any artist would love to explore.”

At the same time, artists say they sometimes struggle to find the proper balance between fact and imagination: How can they grab the viewer’s attention while getting the science right? That can be tricky, involving topics that may be hard to comprehend, let alone visualize.

“Lots of topics are very theoretical and raise questions such as, ‘What does a Higgs boson look like?’” says Greg Stewart of SLAC’s InfoMedia Solutions group. “It’s a challenge, but I enjoy the challenge.”

Joanna Griffin, a graphic arts designer at Jefferson Laboratory in Newport News, Virginia, says, “As an artist you want it to be visually appealing. That sometimes comes into conflict with the science, but you try to strike a good balance.”

|

Back in the day

In the early days of particle physics, simple posters in two or three colors required a pen, ink, complicated stencils known as Leroy templates, and plenty of time.

“I had posters that sometimes I worked on for one or two weeks,” says Anna Gelbart, who recently retired after 26 years as a graphic arts designer at triumf, the Canadian national laboratory in Vancouver, BC. “Everything had to be drawn from scratch.” (See her “Rare Decay Symposium” poster, below.)

Once created, the poster was sent to a professional printer. One common form of reproduction, lithography, required a series of steps: First, light-sensitive chemicals were applied to a metal plate and a negative image of the poster placed on top. Then the plate was exposed to light; wherever the light penetrated, the chemicals disappeared, leaving an image of the poster behind. When ink was applied to the plate it stuck until pressed onto paper during actual printing. Color posters required a separate plate for each color, although they could be applied in rapid succession.

Today, a skilled designer can create a poster in a matter of hours with the aid of programs such as Photoshop and Illustrator. Small quantities may be printed on-site, while larger orders can be placed digitally and delivered by off-site printers in just two days. “The process is a difference of night and day between the old school and new school,” says Anderson. “Mass production used to be an art. Now it’s just production.”

The ability to produce posters in a matter of hours has also raised expectations, and led to ever-quicker turnaround times. “Five years ago people would like posters finished in two weeks. Then it became one week, and today it’s within the hour,” says Fred Ullrich, manager of Visual Media Services at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Batavia, Illinois. “I’m not saying people are demanding; it’s just the way the technology works. Everything is instant, right now, and the time factor is an issue that we’re really struggling with.”

|

To keep up with the demand, some departments have hired designers specifically trained in the new graphic design techniques. Both JLab’s Griffin and SLAC’s Stewart were hired within the past two years. “I’ve always loved science, and this is a great marriage of what I like to do for fun and my love of physics,” says Stewart. “I never had a clue art work like this was going on at particle physics institutions, but it makes perfect sense.”

Engaging the public

Some of Terry Anderson’s most engaging posters advertise colloquia and lectures for lab employees and the public. Deadlines are often tight; he may be approached with a title on a Wednesday for a poster that’s due on Friday. This actually gives him a certain amount of freedom. With no time for committee meetings or discussions about what should appear on the poster, Anderson relies solely on his own imagination and skills.

“Most posters have to be so visually accurate that you never get the freedom to play,” says Anderson. “But the colloquium series allows for that sort of freedom. And most scientists enjoy the art; it makes them feel like stars. Some first-timers can’t wait to see what we create for them.”

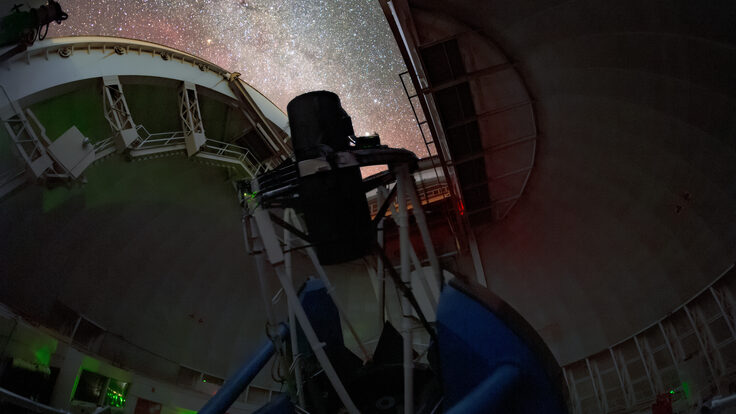

To illustrate a public lecture entitled “The Violent Universe,” for instance, Anderson began with a serene picture of the night sky. A red fist bashes through it, tearing a gash that bursts into flame. “The idea was to symbolize violent forces with the fist,” says Anderson, “and to have the fist viciously breaking through the stereotypical peaceful image of the universe.”

|

Lawrence Krauss, a physics professor and author from Case Western Reserve University, recalls the Godzilla poster that announced his “Science Under Attack!” colloquium at SLAC. “The only input I had in the poster was hearing the general idea and asking if I would mind if it was sort of science fiction-like,” Krauss says. “The final piece was a surprise, and I loved it.” He adds that even when a poster does not quite nail the physics concepts, “if it’s not blatant, and it gets people to the lecture, they will hear what I have to say.”

Looking ahead

Today, the Internet is triggering a new round of poster evolution. Now that every conference and event has its own Web site, there’s no longer a need to list the names of the organizers or other details on the poster, and this allows more creative freedom.

“We use the website to convey as much information as possible, which allows us to keep our e-mail announcements and posters fairly uncluttered,” says University of Texas postdoctoral fellow Kurtis Williams. “Hopefully, this makes them less likely to be deleted, discarded, and forgotten.”

Although more posters are being displayed online, and a growing number are available for download, most conference organizers still distribute hard copies to every major institution where potential attendees might see them, on the theory that people are much more likely to hang onto a poster if it is delivered to them.

|

Meanwhile, graphic designers are exploring new ways to reach audiences—for instance, by creating movies and animations that show physics phenomena, from free-electron lasers and particle colliders to elementary particles, in new and exciting ways. These short films may be what’s needed to catch the attention of a culture accustomed to high-tech special effects.

“Advertising has become much flashier, and tool sets used in movies and television are now readily available for anyone,” says Stewart, who is

working on a long animation of SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source, which is now under construction. It allows the viewer to fly over the completed building and shows how a free-electron laser beam is created.

“Beyond the attractive quality of being able to capture the imagination and attention of the audience, movies and animations can show information to the audience,” says University of California, Berkeley Professor Bernard Sadoulet, who presented a SLAC colloquium on the Cryogenic Dark Matter Search. “We try to show very visually what the laws of physics are telling us, and it often works quite well.”

Although these new technologies show promise, don’t expect them to replace posters at particle physics labs any time soon. “People still like seeing posters sitting up in real space and not on a computer screen,” says Anderson. “The artistic side of posters activates a different part of the brain. They’re like a dessert—or like a scientific appetizer.”

Click here to download the pdf version of this article.