“What happens to a quark deferred?” the poet Langston Hughes may have asked, had he been a physicist. If scientists lost interest in a particle after its discovery, much of what it could show us about the universe would remain hidden. A niche of scientists, therefore, stay dedicated to intimately understanding its properties.

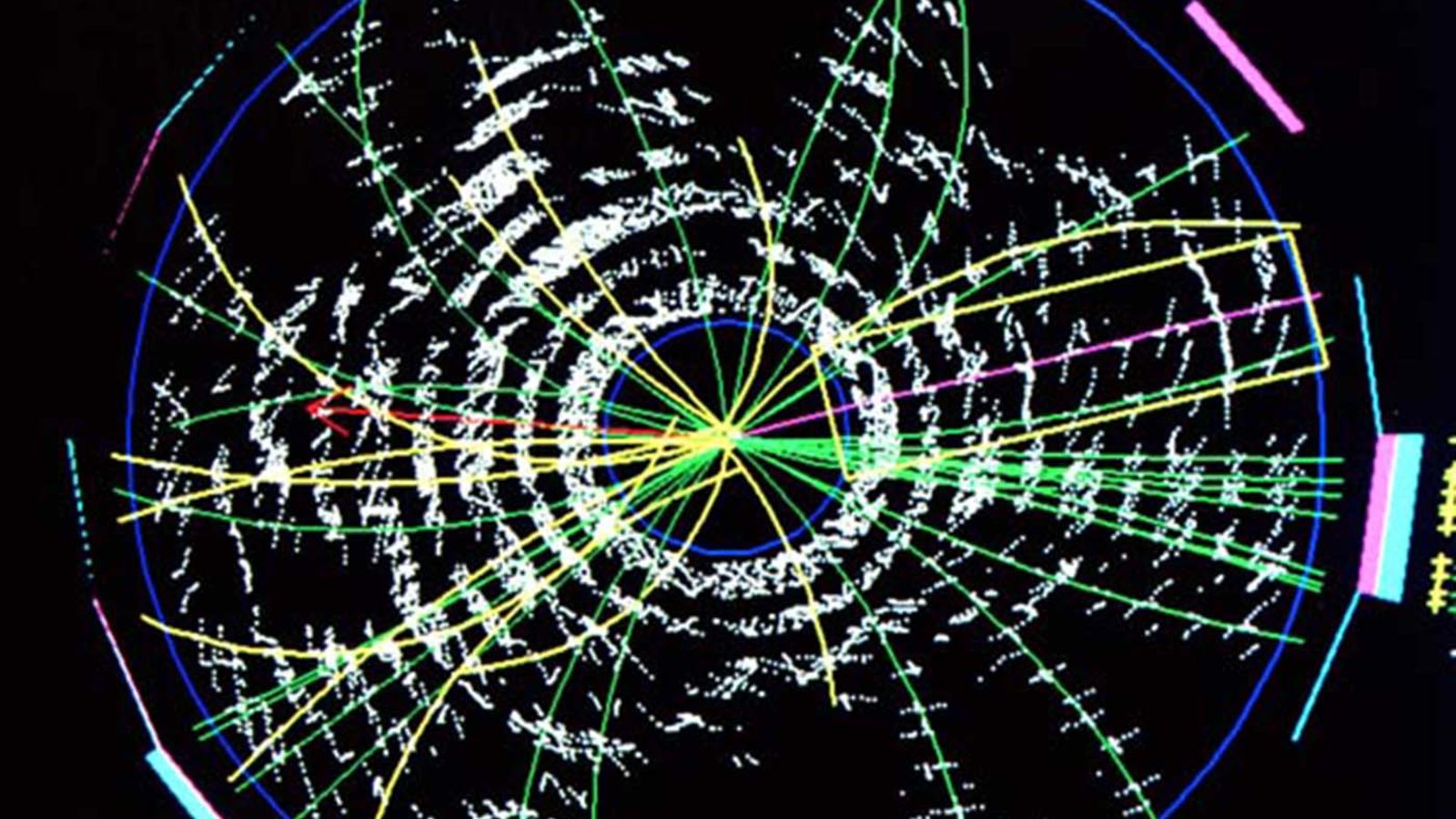

Case in point: Top 2014, an annual workshop on top quark physics, recently convened in Cannes, France, to address the latest questions and scientific results surrounding the heavyweight particle discovered in 1995 (early top quark event pictured above).

Top and Higgs: a dynamic duo?

A major question addressed at the workshop, held from September 29 to October 3, was whether top quarks have a special connection with Higgs bosons. The two particles, weighing in at about 173 and 125 billion electronvolts, respectively, dwarf other fundamental particles (the bottom quark, for example, has a mass of about 4 billion electronvolts and a whole proton sits at just below 1 billion electronvolts).

Prevailing theory dictates that particles gain mass through interactions with the Higgs field, so why do top quarks interact so much more with the Higgs than do any other known particles?

Direct measurements of top-Higgs interactions depend on recording collisions that produce the two side-by-side. This hasn’t happened yet at high enough rates to be seen; these events theoretically require higher energies than the Tevatron or even the LHC’s initial run could supply. But scientists are hopeful for results from the next run at the LHC.

“We are already seeing a few tantalizing hints,” says Martijn Mulders, staff scientist at CERN. “After a year of data-taking at the higher energy, we expect to see a clear signal.” No one knows for sure until it happens, though, so Mulders and the rest of the top quark community are waiting anxiously.

A sensitive probe to new physics

Top and anti-top quark production at colliders, measured very precisely, started to reveal some deviations from expected values. But in the last year, theorists have responded by calculating an unprecedented layer of mathematical corrections, which refined the expectation and promise to realign the slightly rogue numbers.

Precision is an important, ongoing effort. If researchers aren’t able to reconcile such deviations, the logical conclusion is that the difference represents something they don’t know about—new particles, new interactions, new physics beyond the Standard Model.

The challenge of extremely precise measurements can also drive the formation of new research alliances. Earlier this year, the first Fermilab-CERN joint announcement of collaborative results set a world standard for the mass of the top quark.

Such accuracy hones methods applied to other questions in physics, too, the same way that research on W bosons, discovered in 1983, led to the methods Mulders began using to measure the top quark mass in 2005. In fact, top quark production is now so well controlled that it has become a tool itself to study detectors.

Forward-backward synergy

With the upcoming restart in 2015, the LHC will produce millions of top quarks, giving researchers troves of data to further physics. But scientists will still need to factor in the background noise and data-skewing inherent in the instruments themselves, called systematic uncertainty.

“The CDF and DZero experiments at the Tevatron are mature,” says Andreas Jung, senior postdoc at Fermilab. “It’s shut down, so the understanding of the detectors is very good, and thus the control of systematic uncertainties is also very good.”

Jung has been combing through the old data with his colleagues and publishing new results, even though the Tevatron hasn’t collided particles since 2011. The two labs combined their respective strengths to produce their joint results, but scientists still have much to learn about the top quark, and a new arsenal of tools to accomplish it.

“DZero published a paper in Nature in 2004 about the measurement of the top quark mass that was based on 22 events,” Mulders says. “And now we are working with millions of events. It’s incredible to see how things have evolved over the years.”