High-tech marbles and bubblegum

|

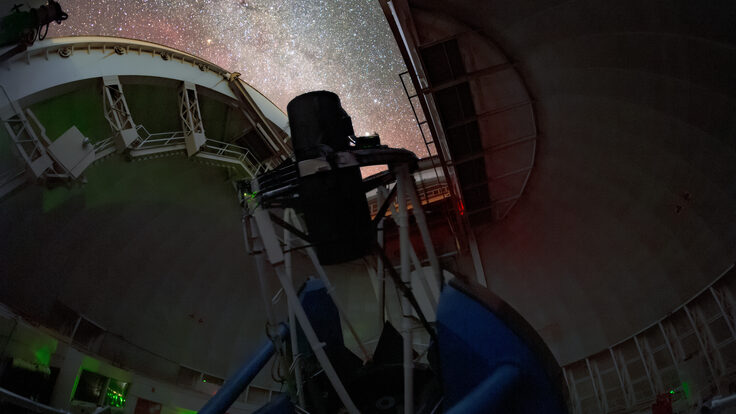

| Photo: Reidar Hahn, Fermilab |

Fermilab scientists are using what look like dime-store toys to polish specialized accelerator cavities, each of which costs about as much as a brandnew Maserati.

Think someone's lost their marbles? Think again.

These superconducting cavities, designed for next-generation accelerators, are made of pure niobium, which is very soft and vulnerable to damage from any scratch or bump during the manufacturing process.

“It's like polishing bubblegum,” says Fermilab's Lance Cooley, who researches superconducting radio-frequency materials like the niobium used to make these cavities.

Yet a smooth finish is vital, because it allows electrons to flow freely and accelerate to nearly the speed of light. So the hunt is on to find the best, cheapest polishing method.

One possible answer: tumbling marbles.

Tumbling is used in industry to remove rough spots from the surfaces of metals. Labs that work with superconducting cavities, such as Germany's DESY and Japan's KEK, have also started to explore the technique. Here's how it works: Place a combination of water and polishing materials inside the superconducting cavity and put it in a special device that spins it around like a Tilt-A-Whirl ride. The materials whoosh around until the inner surface has a mirror- smooth finish.

The marbles used for polishing are not toys. Scientists use only marbles made of fine porcelain—pure aluminum oxide—to prevent contamination of the cavity's inner surface.

Charlie Cooper and his colleagues at Fermilab also are testing other tumbling materials including cork, dried corncobs, walnut wood chips, ceramics, and plastics. At the moment, the tumble-polish process is like a recipe that many have tried but no one has perfected, in part because rigorous testing has yet to be performed.

“We know what works but we don't know why, and we want to find out so we can optimize it,” Cooper says. “We're taking an art and finding the science.”

Daisy Yuhas

Click here to download the pdf version of this article.