A course first offered at Yale University in 2011 is cross-listed in an unusual combination of departments: physics and theatre arts. In the class, instructors Sarah Demers and Emily Coates team up to teach introductory principles in classical and modern physics and in classical and modern dance.

“We realized early on that we are both fierce advocates for our fields,” Demers says. “Emily wants to show people that dance is rigorous and movement research is a serious and intellectual endeavor. I want to show people that physics is creative and lively.

“Our disciplines carry opposing stereotypical strengths and weaknesses, and putting the two together helps us to break these down.”

Coates is the sole full-time dance faculty member and director of dance studies at Yale. Demers is an assistant professor of physics and a researcher on the ATLAS experiment at the Large Hadron Collider.

“It’s not what you might think—just jumping around and measuring spins,” Demers says. “This isn’t ‘Dance Your PhD’ for students. We’re not trying to get people, as literally as they can, to translate physics equations into movement. That’s too simplistic and wouldn’t give dance an equal weight.”

“In the studio work, we explore the effects of physical forces on our bodies and use the scientific concepts as points of departure for creating choreographic studies,” Coates says. “For me, this course seemed like a way to tug our already interdisciplinary dance studies curriculum in a surprising new direction.”

Class time is spent in a dance studio. Equipped with a whiteboard and warmed-up muscles, students might evaluate the torque of two pirouette styles using the vectors created by the dancers’ starting leg positions. In another session, the students may create group choreography based on particle interactions.

Amymarie Bartholomew, a student who participated in the class’s first iteration, is now pursuing a chemistry doctorate at Harvard. She’s also a dancer.

“I wouldn’t normally think, ‘Today, I’m going to choreograph a piece about classical collisions and quantum mechanical wave interference patterns,’” Bartholomew says. “But it’s generative artistically to think far outside the box for inspiration.”

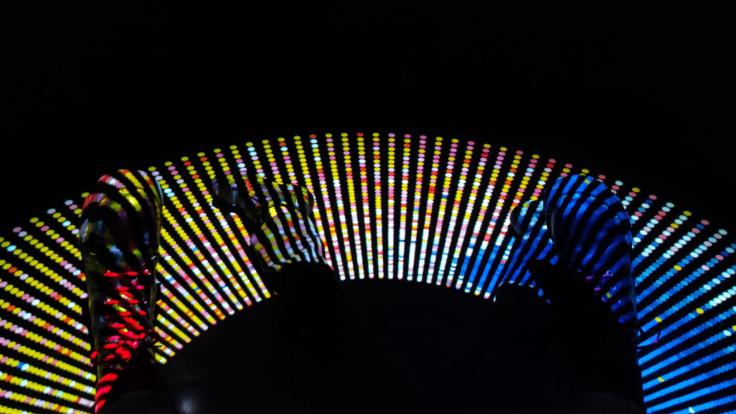

Coates and Demers recently produced a video inspired by the class titled “Three Views of the Higgs and Dance” (still from the video pictured above). In the 14-minute video, which is posted on Vimeo, physicists explain the Higgs boson in dance terms, then their voices are muted and their gestures speak for themselves.

Coates came up with the concept while watching Demers’ movements as she gave a public talk.

“Sarah used a continual sequence of inventive gestures in her Higgs talk,” Coates says. “When we interviewed other physicists, it was a similar thing. They imagined the Higgs kinesthetically. And that leads to a hypothesis we have: Embodied imagination is bound up in scientific discovery.”

Demers says taking part in the dance class has inspired her to think about her research in new ways.

“It would be simpler for all of us to think that our disciplines ask the most interesting questions about life using methods to best match the problem,” she says. “But I’m convinced we have everything to gain by taking another discipline as a serious partner, particularly when they differ as much as particle physics and dance.”