Engineering big upgrades

|

|

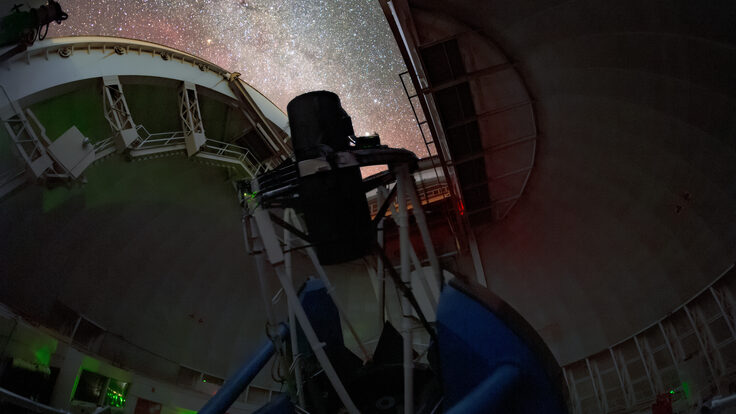

Photo: David Harris |

How do you renovate a delicate, irreplaceable detector? Very carefully.

During the last four months of 2006, the BaBar collaboration at SLAC successfully replaced a prematurely aging muon identification system. Creative and solid engineering played a big role in upgrading a detector that wasn't meant to be taken apart.

Jim Krebs, BaBar's chief engineer for mechanical operations, spent five years on the project. “We had to figure out how to take everything apart.”

In August, crews opened the doors that protect the three-story-tall detector, exposing five layers of detection instrumentation and a nervous system of wires and cables. Graduate students disconnected and then lovingly tied, bundled, and organized the thousands of cables that blocked the way to the muon identification system.

To access the outermost layer of the detector where the muon system resides, the mechanical operations crew used thousands of crane lifts to remove several layers and many tons of steel, including critical pieces where the support arms for the calorimeter detector attach. Protecting the calorimeter was one of the toughest engineering challenges, and required suspending 44,000 pounds, about half its weight. The support scheme performed flawlessly.

Early engineering efforts went into building a special lift to tackle the difficult job of pulling out the old muon detectors and feeding the new ones into narrow slots angled at 60 degrees. The lift fit alongside the front end of the detector with only inches to spare, sandwiched between the beam pipe that pierces the center of the detector and the opened door. The new muon detectors come on one-inch-thick, 12-feet-long flexible sheets. Standing on the lift's platform, crews used the built-in angled tray to help hold the long, delicate sheets in position for insertion.

When everything was put back together and the detector doors closed again, many people let out sighs of relief. Opening the detector required taking a calculated risk because not all of the earthquake protection could stay in place. Now, the refurbished detector is taking data again.

Heather Rock Woods

Click here to download the pdf version of this article.