|

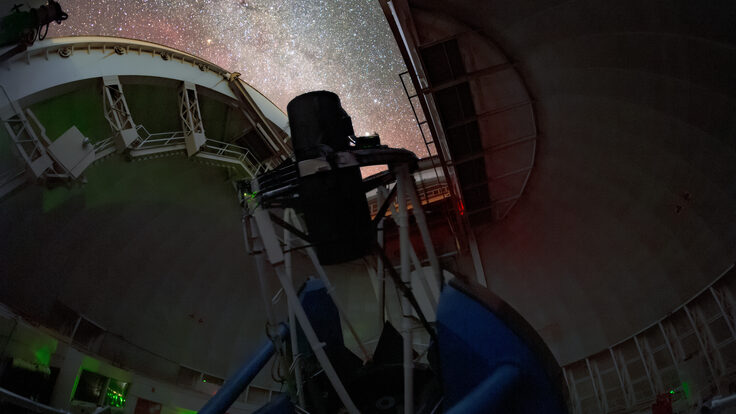

| Photo: Reidar Hahn, Fermilab |

And they lived in physics bliss forever after...

When physicists marry physicists, the beginning may be a 'big bang,' but issues of life, love, and family gravitate toward the universal.

By Mike Perricone

In a physics lab class during his sophomore year at Indiana University, Jason Rieger made a big impression on his lab partner.

"He blew something up," says Leah Welty, who has been Leah Welty-Rieger since Friday, August 13, 2004, when she and Jason were married in her home town of Joliet, Illinois.

Randomly assigned as lab partners, they became self-described "best friends" for a year and a half before actually dating. On a trip to New York City three years later, when both were graduate students in particle physics at Indiana University, they walked to the midpoint of the Brooklyn Bridge, where Jason proposed and Leah accepted.

"We had stopped at a jewelry store in Manhattan to pick out a ring," Leah recalls. "But we had it mailed home to save money on the tax, so then we had to find another ring. Then when we called everyone in the family to give them the news, nobody was home." The news, of course, spread eventually, with the ceremony and celebration taking place a year later on the grounds of a rented mansion in Joliet.

Leah and Jason have now settled into life as graduate students at Fermilab, commuting 40 miles from an apartment on the near-west side of Chicago. Both are researching the physics of the bottom quark as members of the DZero detector collaboration, sharing the same office space, and working to finish their PhD theses.

They "don't buy a lot of extra stuff" on their grad student stipends, Jason says—except for running shoes. Both are marathon runners, and they just completed their second Chicago marathon; both finished in less than four hours for the first time. They want to have children (Leah, an only child herself, wants more than one), and they are envisioning their future with the singular clear optimism of a young married couple.

|

|

|

| Leah Welty-Rieger and Jason Rieger (from left): both are experienced marathoners, including the Chicago Marathon; their wedding took place at a mansion (rented) in Joliet, Illinois; both are working on the DZero experiment at Fermilab. | ||

| Left two photos courtesy of Leah Welty-Rieger and Jason Rieger. Right photo: Reidar Hahn, Fermilab. | ||

"All our friends have real jobs at this point," Leah says. "We hope that with our PhDs, we'll be able to catch up. Our goal is that once we're 30, all those things should be even."

Making things work

Particle physicists might spend much of their professional lives in a phantasmagorical quantum realm, but their personal lives are usually rooted firmly in the everyday world of house and home, children and family, bills and benefits, dreams and realities. When physicists marry physicists, their issues still run the conventional gamut, whether they live in America, Europe, or Asia.

The logistics for dual-physicist couples, however, often adds a flavor of complexity. "Which town shall we live in?" can become "Which country shall we live in?" and "Who picks up the kids while I'm at work in the city?" can transform into "Who picks up the kids while I'm at a conference in Japan?"

Tuula Maki and Mikko Voutilainen are physics graduate students from Finland. They are working on their PhD research at Fermilab and have begun a marital journey similar to that of Leah and Jason. Tuula is from Tampere, and Mikko is from Joensuu; they met as students at the Helsinki University of Technology. "It's the MIT of Finland," Tuula says. They "got along very well" for two years before they started dating, Mikko says, and they became engaged three years later.

|

|

|

| Tuula Maki and Mikko Voutilainen (from left): Tuula and Mikko, both outdoors types, spent part of their honeymoon hiking in the Grand Canyon; they have an apartment in The Village on the Fermilab site; a soft rain was falling on their wedding day, in Kuva, Finland. | ||

| Center photo: Fred Ullrich, Fermilab. Others are courtesy of Tuula Maki and Mikko Voutilainen. | ||

Tuula and Mikko were both board members for the Guild of Physics, a student organization at Helsinki, and Tuula just wound up a term as head of the Graduate Students' Association at Fermilab. "I like to have a role in the field, to help improve student life," Tuula says. They live in a furnished apartment on the east side of the Fermilab site, in the area called The Village, where they are happy to be close to work without worrying about furniture, cars, and commuting.

When they finish their PhDs some time in 2007, both Tuula, now at CDF, and Mikko, now at DZero, anticipate postdoctoral positions at CERN, where the Large Hadron Collider will be starting operations. "I think it should be pretty easy to find positions for both of us," Mikko says. "In particle physics, you stay near the big accelerators, and there should be plenty of experimental groups...We do know some scientists with careers in two different cities, who meet on weekends, although we wouldn't like that."

As for possibly raising a family: "We haven't been thinking about that yet," Tuula says. Mikko adds that he would like to better understand how physics couples who have been married for several years solve problems such as conflicting job offers, and how they manage to raise children with both parents working as physicists.

Juggling children and careers

Patrizia Azzi and Nicola Bacchetta, both physicists, have mastered these issues. They have dealt with raising three children while building careers in physics. Today, they both work on the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) experiment at CERN, with permanent positions at Italy's Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare in Padova. Patrizia says she and Nicola did not give a lot of consideration to the issues of work and travel that double in complexity when both spouses are members of a thoroughly international field. "No, we really did not think very much about it," Patrizia says. "Otherwise we would have never done it!"

|

|

|

| Patrizia Azzi and Nicola Bacchetta (from left): Patrizia in the CDF control room during her Fermilab tenure; Patrizia and Nicola with their first son, Marco; their wedding in 1993 in Verona. The reception was held in the medieval Castelvecchio. | ||

| Left photo: Reidar Hahn. Other photos courtesy of Patrizia Azzi and Nicola Bacchetta. | ||

In what might be compared to the timing of a precision experiment, Patrizia and Nicola had children Marco (May 5, 1999), Lorenzo (May 8, 2001) and Maria (May 9, 2005). "That is not a typo," Patrizia says. Marco and Lorenzo were born in Naperville, Illinois, late in the couple's 14-year stay at Fermilab. Maria was born after they had moved from Fermilab back to Padova, but a month later Nicola moved to CERN to work on CMS. And so they moved to Geneva, Switzerland, where Patrizia also joined CMS following the completion of her maternity leave.

|

With three young children and two full-time physicists now in Geneva, the domestic equations were unlikely to balance. Marco and Lorenzo were enrolled in an English-speaking school, so they wouldn't have to learn a third language (French). Childcare for baby Maria took a bit more creativity and, eventually, luck also lent a hand.

"After a lot of searching," Patrizia says, "we finally found a maman-du-jour, that is a lady that keeps the baby at her house for the day. We like her a lot and we are very happy. She lives five minutes from CERN and she speaks Spanish and French, so it was easier for me to communicate in the beginning. I did not speak any French. The other great thing is that a teacher from the Fermilab [day care center], Patina Waterstreet, who we already knew very well, decided to come live with us as an au-pair for one year—or more?—after her graduation. I'm sure you can imagine that life with three kids and two parents working full-time can be crazy. Now Patina is just part of the family."

Meeting away from home

Patrizia and Nicola are both from northern Italy; Patrizia from Desenzano del Garda and Nicola from Venice. Both attended the University of Padova, but not concurrently. They both worked on the Collider Detector at Fermilab for more than 14 years. They met in 1991, on the day of Patrizia's traumatic arrival at Fermilab.

"I had a bad experience at Immigration because I needed to stay for four months, but my boss did not tell me I had only a three month visa waiver," Patrizia recalls. "My English was very bad. In the end, moved by my tears, Immigration let me in after having me pay 90 dollars for a visa at the airport. I was tired and nerve-wrecked, when another friend took me to the apartment in Country Ridge, behind the Family Foods supermarket, that Padova University was renting. That evening Nicola was also there. And he was not particularly understanding of the situation, telling me I should have known better. Oh well..."

But all went well enough. They were married in November 1993 in Verona. The reception, thanks to Patrizia's father being a former officer in the Italian Army, was held at the Officers' Club in the medieval Castelvecchio.

"It has always worked out in the end," Patrizia says. "Clearly we are very lucky in having kids that are very good, sweet, and healthy. The basic rule was always to stay together, no matter where, instead of having a parent away most of the time. My kids have changed many houses—and they remember them all—but I think they can feel 'at home,' wherever home is. They seem to be nice and happy kids, so we must have done something right."

|

|

|

| Pushpa and Chandra Bhat (from left): their wedding in Bangalore had 1500 guests and extended more than five days; their son, Shreyas, is about to enter graduate school on a physics career path; Pushpa first worked on Fermilab experiments in 1985, and Chandra joined the lab in 1988. | ||

| Left two photos courtesy of Chandra Bhat. Right photo: Reidar Hahn, Fermilab. | ||

Pushpa and Chandra Bhat have been married for 26 years. Pushpa, of the DZero and CMS experiments, and Chandra, of Fermilab's Accelerator Division, are both from India. Pushpa is from a family of white-collar professionals in the city of Bangalore, while Chandra is from a family of farmers in the western mountain region near the Arabian Sea and the coast city of Goa. They met while attending graduate school at Bangalore University in the late 1970s; in fact, when Chandra showed up for an interview at the university, he first was quizzed by Pushpa, the top-ranked student and university gold medalist, before he met with a professor.

Their connection was immediate. They co-authored the first paper that each published, in 1978. "Then, love blossomed," Chandra says, "and we got married in 1980." Pushpa emphasizes that while the marriage was not an arranged one, it was very much a traditional South Indian wedding. "We were married on May 7th in Bangalore," she says. "About 1500 people attended the wedding. The ceremonies took place over five or six days."

It might be the only wedding in the world in which one of the most famous graduate-level physics textbooks played a role. "In ancient India, boys traditionally went to a boarding school, then returned home to seek a bride," explains Pushpa. "The wedding ceremony includes a ritual in which the groom needs to show off his scholarship. Chandra showed up with Jackson's Classical Electrodynamics in hand."

|

Moving abroad

Pushpa and Chandra defended their PhD theses on the same day in Bangalore. They moved to the Netherlands for a few years, then settled as postdocs in Durham, North Carolina, with Pushpa at Duke University and Chandra working in nuclear physics at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. Chandra recalls that they decided not to begin raising a family until finishing grad school and settling-in somewhere. Their son, Shreyas, was born in Durham in 1986. That day, Pushpa's mother arrived and stayed for about seven months to help the new family.

Pushpa had wanted to work at Fermilab since she first became smitten with the knowledge of particle physics and big accelerators. Chandra waited for the right time to change his field to accelerator physics and he joined Fermilab's Antiproton Department in 1988. As a member of the high-energy physics group at Duke University, Pushpa had worked on Fermilab experiments since 1985, and joined Fermilab in 1989. Wanting the best for their son was paramount in accepting a position at Fermilab. In the following years, they stayed at Fermilab instead of seeking academic positions.

"We are both workaholics and have worked non-stop for, oh, however many decades," Pushpa says. "We made the decision to stay at Fermilab and not try to go to a university because if one of us traveled on a regular basis we thought it would be hard on the family and especially for our son. So, we have mainly traveled to conferences/meetings a few times a year and mostly dragged along the other two. These have been great experiences for our son. He has traveled with us to many conferences all over the world and attended our talks. He used to ask questions publicly after our talks, always interesting and sometimes tough ones."

Chandra adds, "Shreyas enjoyed it all thoroughly and hardly complained. By 14, he went to the Illinois Mathematics and Science Academy [a boarding school] and had to live there. I would say the whole experience was great and quite smooth." Shreyas is now a senior at the University of Chicago and is applying to graduate schools, envisioning a career in physics.

|

Words of advice

With their son making his way in the world, and the perspective gained from looking back upon a marriage of achievement and longevity, Pushpa and Chandra are willing to offer insight to younger couples beginning the same pathoffering only because they have been asked.

Chandra emphasizes their mutual respect. "Since both of us understand quite a bit of each other's issues and problems," he says, "we solved them as they occurred. We respect each other's priorities and care for each other's successes, as any couple would." They also respect each other's differences. "I am quite a practical person," Chandra says. "Pushpa is an optimist of the highest order. I have never known anyone more optimistic and hopeful and caring than she is. She is a highly imaginative and creative person too. She, of course, thinks, she could have done more, but being the optimist she is, she thinks that the best is yet to come. Generally our approaches to solving problems are different but the desired effects are the same. It has worked out quite well."

For her part, Pushpa stresses the importance of each partner being a valued and active parent. "Fathers can be soccer dads while also helping with the intellectual and emotional development of the children," she says. "Neither parent should miss those various wonderful phases with their children. Even if you have to pull a late night, you had better go to that concert or show or soccer game. Most of all, it is important that both partners realize that the careers and ambitions of each person are equally important. Then, it is possible to support the other and lend a helping hand."

Pushpa says that it is important for each partner to be valued equally. "The times are very different from when we started our careers," she says. "Physicist couples are now encouraged to strive for the best bargain for both of them in employment." And when they both have their careers, she adds, "It is important to share responsibilities and household duties."

Chandra offers an example. "I cook for us most of the time, and she cooks for us sometimes," he says. "And, in fact, when she has to cook, we go out to eat."

This, of course, is an example of how it can be done.

Click here to download the pdf version of this article.