Gran Sasso: A tale of physics in the mountains

In an epic story of fairy-tale beauty and world-leading science, human courage and determination confront adversity and Gran Sasso laboratory comes forth to see the stars once more.

By Judith Jackson

|

| Photo: Luigi Ottaviani |

"Somewhere," wrote MFK Fisher, the late American writer on food and other human appetites, "there must surely be a folk saying, not in Poor Richards Almanack, perhaps, but of equal logic and simplicity, about how every life has at least one fairy palace in its span."

Fishers fairy palace, encountered at the age of ten, was the Pig n Whistle, a stylish ice cream parlor in 1918 Los Angeles where Mother occasionally took her for a treat. In the realm of underground laboratories, for some physicists that magical palace of a lifetime must be the Laboratori Nazionali del Gran Sasso. The largest underground science laboratory in the world casts an extraordinary spell.

Of course, the logic of enchanted castles decrees a quota of dragons to slay before all can live happily ever after. And in true enchanted kingdom form, Gran Sasso has battled epic perils that have sometimes come scarily close to breaching the castle gates. The unfolding story of this remarkable mountain laboratory has all the drama of a tale by the Brothers Grimm.

Snow, sheep, spaghetti, science

What is it that makes Gran Sasso so magical? For one thing, its beautiful. At 1000 meters, in the heart of a national park in Italys highest mountain range south of the Alps, the snowcapped peaks of the Abruzzo mountains ring the campus, outlined against the sky. Weathered tile roofs climb the steep streets of tiny stone towns, and flocks of sheep would block traffic on the mountain roads if there were any traffic. Its only a 130-kilometer trip from car-choked Rome, but Gran Sasso is a world away.

For another, theres the food. Those sheep? Think cheeses so local theyre unknown beyond the next valley, and tiny "burn-your-fingers" lamb chops that taste of mountain mint and thyme. The Abruzzesi make their characteristic pasta with a wire device called a chitarra, because it looks like a guitar. And although the region doesnt produce a lot of it, olive oil from the Abruzzo is claimed to be the best in Italy. After work, in Marias restaurant five minutes up the mountain from the lab, everyone–lab people, townspeople, the mayor–knows everyone else, the children fall asleep in a heap on a couch in the corner, and people eat the way MFK Fisher would want them to.

Having breathed the mountain air and eaten magnificently, its time to do science. To reach the underground experiments at Gran Sasso, unlike the case for many other underground laboratories, scientists dont take an elevator. They hop in the car. Gran Sasso, one of four Italian national laboratories funded by the Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare, or INFN, is among the few underground laboratories (Canfranc and Modane are others) with drive-in access. From the above-ground campus near the hamlet of Assergi (population 524), physicists and visitors take the expressway west through a 10-kilometer tunnel underneath the Gran Sasso mountain. A "lab-only" turn-off shunts them back eastward through the tunnel to a special exit for the underground galleries. And what underground galleries they are–three huge, bright experimental galleries, each about 100 meters long, 20 meters wide, 18 meters high, for a total volume of 180,000 cubic meters. First-time visitors catch their breath. Wow.

|

| Winter roads call for chains or snow tires. |

Drive-up window on the universe

A drive-in laboratory has distinct advantages. Most strikingly, experimenters can truck in giant detector components and materials, rather than sending tiny pieces, ship-in-bottle style, down a narrow elevator shaft for reconstruction below. Experimenters can easily come and go, and the laboratory avoids the costs, maintenance, and safety concerns of elevators. Overhead, Gran Sassos 1400 meters of rock shelter the experiments, reducing cosmic-ray noise from space by a factor of a million. Thanks to the low level of natural radiation in the native rock, the rate of neutron interactions in the galleries is a thousand times less than on the earths surface.

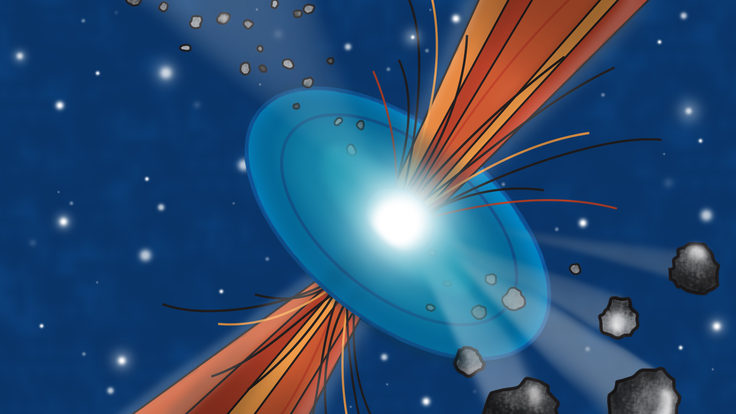

Protected from bombardment, Gran Sasso experimenters investigate dark matter, nuclear astrophysics, and the physics of neutrinos. For some of these experiments, observing three or four events per year would constitute a scientific breakthrough. To hear these whispered intimations of discovery, experimenters must escape the deafening background chatter of billions of particle events on the earths surface. For underground physicists, experimental design, techniques, materials, and location all aim at one goal: victory over backgrounds. The underground galleries provide the cosmic peace and quiet that these physicists need in order to have a hope of detecting incredibly rare interactions. For Gran Sassos 750-plus scientific users, underground physicists from 24 countries including the United States, the laboratory might be paradise.

Gran Sasso isnt paradise, of course. At times, over the past two decades, it has seemed less like il Paradiso and more like lInferno. Perhaps ironically, most of Gran Sassos severest troubles have come from the same sheltering mountain and convenient highway that make it such a remarkable place for underground science.

|

| Luigi Ottaviani At Marias restaurant, five minutes from the laboratory campus, lab people, townspeople, and families share meals of extraordinary "cucina Abruzzese." |

|

| Attanasio Candela |

Troubled waters

The laboratory shares Gran Sasso mountain not only with the high-speed A24 expressway linking Rome to the Adriatic, but also with a major aqueduct that sends some 1500 liters of water per second rushing into giant pipes that supply drinking water to the city of Teramo, 40 kilometers down the mountain to the east. Construction of the highway began in 1969 and finished in 1982, with the associated laboratory and aqueduct construction complete in 1988. From the earliest days of construction, changes in the local water table attracted the attention of Italian environmentalists.

A 2005 paper by Italian university geologists in the Giornale di Geologia Applicata summed up the issue:

"Tunnels, although being built for different uses, may drain groundwater even after completion of their lining. In some instances, it is extremely difficult or impracticable to restore the original hydrodynamic equilibrium, with consequent risks of exhaustion of springs, change in the relations with adjacent hydrogeological structures, depletion of groundwater reserves, etc. Tunnel construction also can alter water supply for drinking, irrigation and industrial uses, with major economic and social repercussions on wide neighbouring areas." (Italics added.)

The laboratory had been experiencing those repercussions for more than a decade when, in August 2002, environmental calamity struck. As they were filling the detector for the Borexino solar neutrino experiment, two US collaborators spilled 50 kilograms of pseudocumene, a liquid scintillator with a strong characteristic odor. The physicists contained the spill and the lab reported it to local authorities, but not before some of it drained into a nearby creek, where picnickers smelled it. A dead fish turned up at the scene. The citizens of Teramo reacted with rage, and the spill became a cause célèbre for environmental activists all over Italy and beyond. They took the matter to the Italian courts and in May 2003, a court-ordered report found that the drainage systems of the laboratory and the highway were not leak tight and could contaminate water supplies. In July 2003, the Council of Ministers declared a state of emergency for all Gran Sasso facilities, including the highway, the laboratory, and the water system. The laboratory immediately shut down any and all underground operations that involved liquids. Some in the science community feared that Gran Sasso might never open its doors to experiments again.

|

End of a tunnel

Meanwhile, the motorway, Gran Sassos other underground tenant, was causing another problem for the beleaguered laboratory. The highway that provides such easy access for scientists is the only way in–and the only way out. In the event of a traffic blockage in the west-bound tunnel of the A24, experimenters would be stuck in the laboratory with no means of escape. And, in fact, in May 2004, a truck fire in the tunnel stopped traffic for hours.

To address this safety issue and to provide a direct route between the underground lab and the surface campus, the Italian government had long planned to construct a third tunnel, above the existing two. Along with the new tunnel, plans called for enlarging the underground laboratory space. Not surprisingly, environmentalists opposed the project, and after the establishment of the national park in 1992, new construction within it became very difficult. During the state of emergency following the Borexino spill, the government used funds originally intended for the tunnel to address the immediate water-related problems. By 2004, given the controversy surrounding the existing structures and the diversion of funds, building another tunnel had become, in the words of one Gran Sasso physicist, not so much a third tunnel as a political third rail. The laboratory had to accept that it would probably never be built, and that the underground space for science at the Gran Sasso site would not expand.

|

| A special exit from the A24 motorway tunnel brings scientists to Gran Sasso's underground galleries. Photo: Luigi Ottaviani |

|

| The laboratory shares Gran Sasso mountain with an aqueduct that supplies water to neighboring communities. Photo: Luigi Ottaviani |

Incipit vita nova: The new life begins

Those difficult days marked the start of a major turn-around effort for the laboratory and its funding agency, INFN. Following the Borexino spill, Gran Sasso took immediate steps to seal off the laboratorys drains and water systems from the aqueduct. Beginning in 2004, they leak-proofed the floors and installed new leak containment wells, part of a completely new drainage system. Along with new water ducts in the freeway, these changes ensured that laboratory operations could never again contaminate local water supplies. Installation of a second independent ventilation system provided the means to bring fresh air into the laboratory in case of a tunnel fire. New highway lighting and better traffic monitoring and control were all aimed at making the laboratory and the highway as safe and environmentally sound as possible.

Laboratory policy increasingly emphasized environmental responsibility, with the central tenet "to develop knowledge of nature in its more intimate structure while respecting nature itself." Relations with neighboring communities have taken a U-turn for the better, thanks in part to an extensive program of science education and outreach to communities in the Abruzzo region and beyond. Programs for students and the public draw some 8000 visitors a year. Gran Sassos annual physics summer school sends 20 Abruzzo students to Princeton University for three weeks of physics immersion. With INFN support, Gran Sasso scientists worked with the Teramo provincial and city governments to create the Galileium, a stylish and accessible astroparticle physics museum near the citys railroad station. Good relationships with the community are a priority, says Gran Sassos new director, particle astrophysicist Lucia Votano, who took over in September 2009.

The Borexino experiment resumed operations in 2005 and began taking data in May 2007. In late August 2006, CERN sent the first beam of muon neutrinos from its Super Proton Synchrotron accelerator to Gran Sasso for detection by the OPERA experiment. Soon, the scientific world expected to hear that OPERA had caught muon neutrinos in the act of morphing into tau neutrinos during their three-millisecond trip from Geneva–the first direct observation of the appearance of one type of neutrino from a beam of another type. The largest concentration of world-leading dark matter experiments made their home at the laboratory.

Things at Gran Sasso were definitely looking up.

Thence they came forth

Then, at 3:32 on the morning of April 6, 2009, a magnitude 6.3 earthquake struck the Abruzzo, its epicenter near the medieval city of LAquila, 20 kilometers from Gran Sasso. The quake caused an average 25-centimeter lowering of the surface in a 12-square-kilometer region around the city. More than 300 people died, some 15,000 were injured, more than 60,000 people lost their homes, and LAquila lay in ruins. While subsequent inspections revealed that the laboratory itself had sustained little damage, and normal operations resumed on May 4th, some 80 percent of staff lost their homes. Almost immediately, INFN went into action, working with the laboratory to find temporary staff housing in nearby hotels and even in specially adapted shipping containers on the Gran Sasso campus. Flexible work schedules, financial help, and an on-site childrens center supported laboratory families as they attempted to cope after the earthquake. Nearly a year later, their lives are far from returning to normal.

"Now," Votano says, "the April earthquake has raised another big challenge, the need to contribute to the new beginning of the social and economic life of LAquila territory in which the laboratory is based."

As part of the effort to rebuild the city, with support from corporate and individual donations, Gran Sasso laboratory and the city of LAquila have joined forces to develop a new planetarium and science center for the city. It will take shape in the Parco del Sole, adjoining the badly damaged 13th-century Santa Maria di Collemaggio, LAquilas most famous and beloved church.

For its inspiration, the Parco del Sole project turned to Dantes Divine Comedy: "And thence we came forth to see the stars once more."

Its a good motto for Gran Sasso Laboratory too. Here mountains and water, neutrinos and dark matter, scientists, students, lovers of nature, not to mention some of the best food in Italy, come together to create a unique human vantage point on the mysteries of the universe. Through trials and triumphs, the laboratory and its people have come forth to see the stars once more. In the end, better than a magic palace, Gran Sasso is an utterly human place, entirely of the real world, a meeting point for science and civilization.

|

| The OPERA experiment in Hall C of Gran Sassos underground research galleries searches for neutrino oscillations beneath 1400 meters of sheltering rock. Photo: Francesco Arneodo |

Generation Gran SassoI joined Gran Sasso laboratory in October 1994, when the lab was in its infancy. The science was vibrant; we were in the hottest time for the solar neutrino problem. The possibilities for new ideas and new projects seemed endless. The contrast between the rural atmosphere of the little town of Assergi and the lab was striking–the white blanket of snow in winter, the scorching heat of the summer, the lunar landscape of Gran Sasso. Sheep over Campo Imperatore, old farmers moving crops on donkeys backs, and, hundreds of meters below your feet, an ultramodern lab gazing at the deepest secrets of the cosmos. No surprise that so many scientists fell in love with it, among them the young Italian scientists who took the baby steps of their careers at Gran Sasso. I am part of a generation of scientists trained by INFN at Gran Sasso that ended up filling physics departments and labs all around the Western world. In my 16 years of work at Gran Sasso, I witnessed transformation. Old physics problems have been solved, and even more intriguing questions have opened up. The very rural Abruzzo I met in 1994 is now long gone. LAquila morphed into a vibrant town, with a pleasant downtown and an interesting night life. It all came to a sudden stop on April 6, 2009. The earthquake brought endless grief, and yet more transformation. The little town of Assergi, unmodified for centuries and untouched by the earthquake, is now booming with new construction to accommodate hundreds of displaced inhabitants from LAquila. I take pride in my ongoing association with Gran Sasso. With so many open problems in particle astrophysics, it is still the place to be. My love affair continues with the region that adopted me and that now I call home. Cristiano Galbiati, Princeton University |

Click here to download the pdf version of this article.