Science fiction asks the question “What if?” and then attempts to answer that question with a story grounded in science fact. That’s why Comma Press, for its latest anthology, paired science fiction writers with CERN scientists, to create untrue stories with a bit of truth in them.

Creating the anthology, titled Collision, started with a call to CERN researchers and alumni of the European physics research center, asking them to describe concepts they thought would inspire good creative writing. Next, authors picked the ideas that called to them most. Each author then met with the scientist who proposed their chosen idea and discussed the science in detail. The anthology consists of a collection of the resulting stories, each with an afterward by the consulting scientist.

Symmetry interviewed three different writer-scientist pairs to learn what it was like to participate in this unusual collaboration: Television writer, television producer and screenwriter Steven Moffat, famous for his work on the tv series Doctor Who and Sherlock, worked with Peter Dong, a physics teacher at the Illinois Math and Science Academy who works with students to analyze data from CERN. Poet, playwright and essayist lisa luxx worked with physicist Carole Weydert, now leader of a unit of an insurance regulatory authority in Luxembourg. And UK-based Short Story Fellow of the Arts Foundation Adam Marek worked with Andrea Giammanco, who continues to do research at CERN as a physicist with the National Fund for Scientific Research in Belgium.

“I just love the idea that a bunch of very serious-minded scientists wondered if the universe might be actively trying to stop them.”

Although the assignment was the same for every pair, they all approached their stories differently.

Steven Moffat and Peter Dong

When Peter Dong first got the call for inspiring physics concepts, he knew exactly what to submit: a strange but real-life theory proposed by physicists Holger Bech Nielsen and Masao Ninomiya.

In the late 2000s, the theorists posited that the universe might for some reason prefer to keep certain fundamental particles—say, the Higgs boson or particles of dark matter—a mystery. So much so, they wrote, that the universe was actively conspiring against their discovery.

The search for the Higgs certainly wasn’t easy. Only weeks after being turned on for the first time, the Large Hadron Collider at CERN experienced a critical failure, immediately stopping the two most advanced experiments aimed at finding the Higgs. Years earlier and an ocean away, the United States Congress suddenly scrapped plans to build a similar collider in Texas, despite construction having already begun.

These two events, Nielsen and Ninomiya argued, could indicate that discovering the new particle was so improbable that the universe wouldn’t allow it to happen.

Dong first read about the theory as a graduate student at the US Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in 2008. “While the probability is absurdly small, and it's a wacky, out-there idea, it's still not impossible,” he says. “When we come up with these wacky theories, I feel like more people should know about them. They're just so much fun.”

In their paper, Nielsen and Ninomiya proposed an experiment that—while it would not prove their hypothesis—could at least put it to the test: Shuffle a deck of a million cards in which a single card is marked “Shut down the LHC.” If that card were randomly pulled from the deck, they would take that as a sign the universe wanted physicists to back off.

The card experiment was never run, and in the end, scientists were able to repair and restart the LHC. In 2012, physicists on the CMS and ATLAS experiments announced the discovery of the Higgs.

Dong had previously tried out using Nielsen and Ninomiya’s idea as the basis for a story while auditing a creative writing class, so when he got the CERN email, he was ready with a pitch.

Writer Steven Moffat says Dong’s idea stood out to him on the list. “I zeroed in on that prompt—one, because I understood it, or at least I thought I understood part of it,” he says. “And two, because I could see a story in it. I just love the idea that a bunch of very serious-minded scientists wondered if the universe might be actively trying to stop them.”

Moffat and Dong worked together to make sure the science in the story held up. “Steven was taking great pains to ask ‘Does this make sense? Would that be right?’” Dong says.

The result was a “mad, paranoid fantasy,” Moffat says. “But it’s decorated in the right terminology and derives from something that really happened.”

lisa luxx and Carole Weydert

Not all the stories in Collision fall neatly into the sci-fi genre. For her entry, poet lisa luxx explored her lived experiences of adoption and migration through the lens of quantum physics. “At a certain point, I had to disentangle [pun not intended] myself from trying to achieve a particular genre,” luxx says.

The writer chose a prompt related to supersymmetry, which posits that every particle has a yet unobserved partner with some shared properties. Like Moffat, luxx says she was attracted to the idea she chose because it made some amount of sense to her. “The physicist had used quite a poetic quote in her explanation of this theory,” luxx says. “That immediately drew me in.”

Physicist Carole Weydert, who submitted the idea, may have had an artistic way of explaining supersymmetry because she had previously explored another complex physics theory in her own art. “It is this idea that you could have a kind of symmetry between everything contained in spacetime and spacetime itself,” she says.

Weydert says she “[tries] to squeeze in time to paint,” sometimes using ripped and cut pages from old textbooks in her work. “I try to express this quest for simplification in theoretical physics, that from one very, very basic theory, the whole complexity of the world emerges.”

It was not easy to translate the mathematical and theoretical aspects of supersymmetry into a fictionalized story, luxx says. “The most challenging part was me grasping exactly the nuance of where physicists are at with understanding supersymmetry,” she says. “I was learning the theory while writing it.”

But the theory eventually clicked into place as a metaphor.

The poet says she wanted to ground the story in a common language to show how entwined physics is with everyday life. “Physics are just parts of us. We can't understand ourselves and can't understand society without at least somewhat understanding these theories.”

The final piece strayed from Weydert’s initial prompt, but Weydert says she is nevertheless pleased with the outcome. “I think what is important in these stories is not the science, as such, but connecting it to something that conveys an emotion.”

Adam Marek and Andrea Giammanco

For his contribution to the anthology, short story writer Adam Marek moved away from traditional prose. He instead wrote his piece in the form of an interview for real-life BBC Radio program Desert Island Discs. The 45-minute show tells the story of a famous person’s life through music tracks they have chosen.

“I’ve always loved it as a format for telling the story of someone’s life,” Marek says. “And I'd thought it could make a terrific framework for writing a short story.”

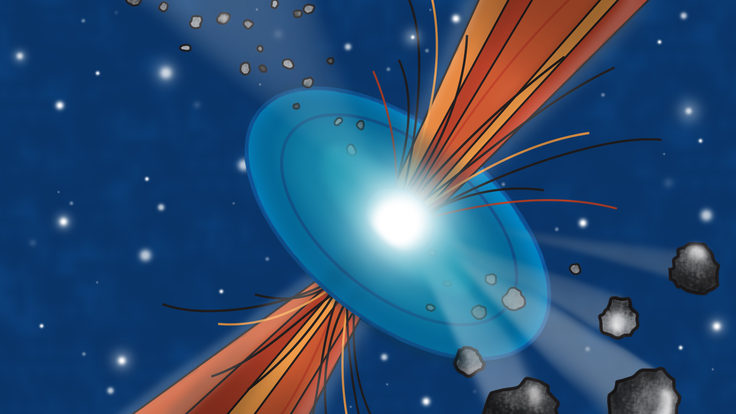

The prompt Marek chose came from physicist Andrea Giammanco. As a postdoc, Giammanco had spent time researching the dark sector, a collection of hypothetical particles that have thus far gone unobserved. “I was in love with the idea of the dark sector popping up in unconventional ways,” Giammanco says.

Marek had worked with other scientists on stories for other Comma Press anthologies, but he says this time was unique. “It was different,” he says. “And I think that was because of Andrea’s particular interests and approach.”

Marek and Andrea spoke many times throughout the project, on video calls and email, Marek says. It helped that they shared a love of science fiction. “Andrea seemed as fascinated by the writing process as I was with the science. We had lots of questions for each other.”

Giammanco says they threw so many ideas at each other “that we could have easily written five completely different stories.”

In one of these brainstorming sessions, Giammanco says he mentioned offhand that the dark sector may be hiding in plain sight, and it may even be revealed in a reanalysis of old data. “This piqued Adam’s attention,” he says—and it ultimately became a key part of the plot.

Throughout the process Giammanco ensured that everything in the story was at least possible. “Adam wanted the idea to work from the narrative point of view,” he says. “But for me, it was paramount to make it work from the scientific point of view.”

But staying within the realm of the possible didn’t restrict Marek and Giammanco to the realm of the particularly plausible. Marek says that flexibility helped him find a creative way for the story to end.

“At the peak of being very stressed out about the story and not knowing how to finish it,” he says, “Andrea just happened to send me an email about ghosts.”

Giammanco had sent Marek an article that quoted physicist and pop culture figure Brian Cox asserting that the LHC had unintentionally disproved the existence of incorporeal beings by failing to detect any evidence of them. But Giammanco had laid out an alternative argument: If ghosts did exist, they would just need to be a part of the dark sector, which the LHC has not been able to reach. “It just fixed it all,” Marek says. “It was really, really fortuitous for the story.”

Whether or not any of the ideas in the stories collected in Collision turns out to be true, the project highlights what both writers and scientists have in common: the ongoing quest to imagine “What if?”