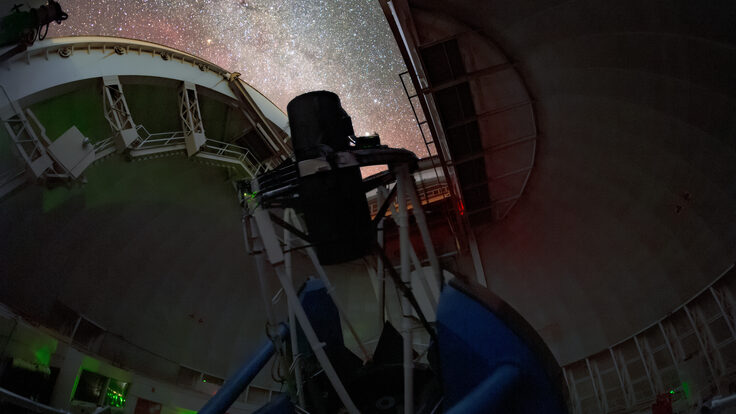

More than a mile up in the San Gabriel Mountains in Los Angeles County sits the Mount Wilson Observatory, once one of the cornerstones of groundbreaking astronomy.

Founded in 1904, it was twice home to the largest telescope on the planet, first with its 60-inch telescope in 1908, followed by its 100-inch telescope in 1917. In 1929, Edwin Hubble revolutionized our understanding of the shape of the universe when he discovered on Mt. Wilson that it was expanding.

But a problem was radiating from below. As the city of Los Angeles grew, so did the reach and brightness of its skyglow, otherwise known as light pollution. The city light overpowered the photons coming from faint, distant objects, making deep-sky cosmology all but impossible. In 1983, the Carnegies, who had owned the observatory since its inception, abandoned Mt. Wilson to build telescopes in Chile instead.

“They decided that if they were going to do greater, more detailed and groundbreaking science in astronomy, they would have to move to a dark place in the world,” says Tom Meneghini, the observatory’s executive director. “They took their money and ran.”

(Meneghini harbors no hard feelings: “I would have made the same decision,” he says.)

Beyond being a problem for astronomers, light pollution is also known to harm and kill wildlife, waste energy and cause disease in humans around the globe. For their part, astronomers have worked to convince local governments to adopt better lighting ordinances, including requiring the installation of fixtures that prevent light from seeping into the sky.

Many towns and cities are already reexamining their lighting systems as the industry standard shifts from sodium lights to light-emitting diodes, or LEDs, which last longer and use far less energy, providing both cost-saving and environmental benefits. But not all LEDs are created equal. Different bulbs emit different colors, which correspond to different temperatures. The higher the temperature, the bluer the color.

The creation of energy-efficient blue LEDs was so profound that its inventors were awarded the 2014 Nobel Prize in Physics. But that blue light turns out to be particularly detrimental to astronomers, for the same reason that the daytime sky is blue: Blue light scatters more than any other color. (Blue lights have also been found to be more harmful to human health than more warmly colored, amber LEDs. In 2016, the American Medical Association issued guidance to minimize blue-rich light, stating that it disrupts circadian rhythms and leads to sleep problems, impaired functioning and other issues.)

The effort to darken the skies has expanded to include a focus on LEDs, as well as an attempt to get ahead of the next industry trend.

At a January workshop at the annual American Astronomical Society (AAS) meeting, astronomer John Barentine sought to share stories of towns and cities that had successfully battled light pollution. Barentine is a program manager for the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA), a nonprofit founded in 1988 to combat light pollution. He pointed to the city of Phoenix, Arizona.

Arizona is a leader in reducing light pollution. The state is home to four of the 10 IDA-recognized “Dark Sky Communities” in the United States. “You can stand in the middle of downtown Flagstaff and see the Milky Way,” says James Lowenthal, an astronomy professor at Smith College.

But it’s not immune to light pollution. Arizona’s Grand Canyon National Park is designated by the IDA as an International Dark Sky Park, and yet, on a clear night, Barentine says, the horizon is stained by the glow of Las Vegas 170 miles away.

In 2015, Phoenix began testing the replacement of some of its 100,000 or so old streetlights with LEDs, which the city estimated would save $2.8 million a year in energy bills. But they were using high-temperature blue LEDs, which would have bathed the city in a harsh white light.

Through grassroots work, the local IDA chapter delayed the installation for six months, giving the council time to brush up on light pollution and hear astronomers’ concerns. In the end, the city went beyond IDA’s “best expectations,” Barentine says, opting for lights that burn at a temperature well under IDA’s maximum recommendations.

“All the way around, it was a success to have an outcome arguably influenced by this really small group of people, maybe 10 people in a city of 2 million,” he says. “People at the workshop found that inspiring.”

Just getting ordinances on the books does not necessarily solve the problem, though. Despite enacting similar ordinances to Phoenix, the city of Northampton, Massachusetts, does not have enough building inspectors to enforce them. “We have this great law, but developers just put their lights in the wrong way and nobody does anything about it,” Lowenthal says.

For many cities, a major part of the challenge of combating light pollution is simply convincing people that it is a problem. This is particularly tricky for kids who have never seen a clear night sky bursting with bright stars and streaked by the glow of the Milky Way, says Connie Walker, a scientist at the National Optical Astronomy Observatory who is also on the board of the IDA. “It’s hard to teach somebody who doesn’t know what they’ve lost,” Walker says.

Walker is focused on making light pollution an innate concern of the next generation, the way campaigns in the 1950s made littering unacceptable to a previous generation of kids.

In addition to creating interactive light-pollution kits for children, the NOAO operates a citizen-science initiative called Globe at Night, which allows anyone to take measurements of brightness in their area and upload them to a database. To date, Globe at Night has collected more than 160,000 observations from 180 countries.

It’s already produced success stories. In Norman, Oklahoma, for example, a group of high school students, with the assistance of amateur astronomers, used Globe at Night to map light pollution in their town. They took the data to the city council. Within two years, the town had passed stricter lighting ordinances.

“Light pollution is foremost on our minds because our observatories are at risk,” Walker says. “We should really be concentrating on the next generation.”