Alfredo “Fefo” Aranda was a high school senior in Juarez, Mexico, when he made one of the most important discoveries of his life: Flipping through a brochure from the University of Texas at El Paso, he found a page with “Physics” at the top and realized that the subject he loved in school could be a career.

To the young Aranda it seemed like a long shot, even though UTEP hugs his hometown on the other side of the US-Mexico border. He had never met a working scientist. He didn’t have much money, and he didn’t speak English.

With encouragement from his father, he made the leap. After completing his bachelor’s degree in physics at UTEP in 1996, he went on to get a PhD at William and Mary in 2001 and do a postdoc at Boston University in 2003.

He still calls the moment he landed on the “Physics” page “a great coincidence.”

“It gives me vertigo to think about it,” Aranda says. “I discovered a wonderful life. But it also haunts me that it might never have happened.”

Today, as vice president of research at the University of Colima in Mexico, his main occupation is building a more certain route to a research career for Latin American students. He does this by providing them with challenging academics and international connections.

It’s a path he and many other Latin American researchers who completed their studies abroad have followed. “Coming from a country in which the path towards becoming a scientist was very circumstantial makes you think about other kids that might want to do science,” Aranda says. “You feel like you can help them.”

There are many stories like his in particle physics and astrophysics—but not because Latin American researchers are uniquely generous, he says; it’s a product of circumstances. “If you’re in a country in which the educational system was pretty much set and it wasn’t a big deal for you and the path was very clear from the beginning,” you don’t need to think about how to build a new path for the next generation. “It’s nice that we think about these things, but I would prefer it if we didn’t have to.

Aranda started the Physics and Math Department at Colima in the early 2000s with three other scientists, including his high school friend and mathematician Ricardo Saenz, who also studied at UTEP. The friends, who both identified as “geeky students,” met through an amateur astronomy club in Juárez. In college they dreamed of returning to their home city and creating a science program, but the circumstances were too challenging.

“After getting my PhD, I started to look at universities in Mexico with physics departments, but I didn’t like a lot of the hiring practices and the treatment of students,” Aranda recalls.

That’s when an unexpected call came from Colima, from an institution at the edge of the Pacific Ocean without a program in physics and math. An administrator that Aranda and the group of young scientists had met at a Cornell University summer school wanted to know if they were serious about their ambitions.

Aranda visited the university in its coastal setting south of Puerto Vallarta in 2001: “It was paradise,” he recalls. Between 2002 and 2004, Aranda, Saenz, Paolo Amore and Andrés Pedroza each moved to Colima, and together they founded the new department.

“We wanted to create a program that would get more kids into science without having to leave our research, so each faculty member conducts independent scientific work,” Aranda says.

In fact, a robust research portfolio is a requirement for all new professors in their program, along with the ability to mentor undergraduate students. Each year since 2007, a class of eight to 10 students has graduated and gone on to either PhD programs in the United States or Europe, grad school in Mexico or industry jobs.

One of those students, Jorge Torres from Colima, says he fell in love with science when Aranda came to his high school to give a talk.

Torres is now a PhD candidate at the Ohio State University and works on the Askaryan Radio Array, a neutrino experiment based in the South Pole. He says what he appreciated most about the undergraduate program was its focus on “personal interaction between professors and students to prepare each of us to compete internationally.”

He says back in high school he never imagined that he would be where he is today. “I’m a rock star to my family,” he says with a chuckle. “They miss me, but they know I am doing well.”

Aranda’s own research connects students to collaborators all over the globe. His work focuses on physics beyond the Standard Model, and he is a member of the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE), hosted by the US Department of Energy’s Fermilab. The international collaboration brings together 1000-plus scientists from more than 30 countries. The University of Colima is partnering with DUNE to send students to the United States for three months to a year to work on the experiment.

“Sixteen years ago there were not many universities in Mexico where you could find research-level academics in the fields of physics and math,” Saenz says. “Our goal has always been for students to be prepared to go to grad school abroad—it’s very challenging, but the students know the aim from the beginning.”

Putting Puerto Rico on the HEP map

Retired physics professor Angel López says his career was based on equal parts success, failure and chance.

In middle school he read an article in a scholastic magazine about the omega particle discovered at Brookhaven National Laboratory, which piqued his interest in physics. He eventually chose physics over medicine for an undergrad major at the University of Puerto Rico. He was accepted to Yale for grad school, flunked out after his first year, but then tried again at the University of Massachusetts, where he discovered experimental physics.

That turn of events landed him at Brookhaven Lab for his doctoral thesis, looking for a rare decay of the kaon particle. “I thought it was incredible,” he remembers. “I read about this in middle school and here I am!”

What López calls luck, many others would call persistence. Once he found experimental physics, he knew it was his source of inspiration, one that he would take home to Puerto Rico and share with the next generation.

After getting his PhD, López conducted solar energy research at a federal energy and environment center near the Mayagüez campus of UPR. The program seemed promising during the energy crisis of 1979, but after the price of oil fell and President Ronald Reagan commercialized energy, drastic cutbacks in funding practically shut the center down.

In 1985 López was offered a job at UPR. He wanted to get back to his previous research, but the landscape looked pretty bleak for experimental physics in Puerto Rico, López says.

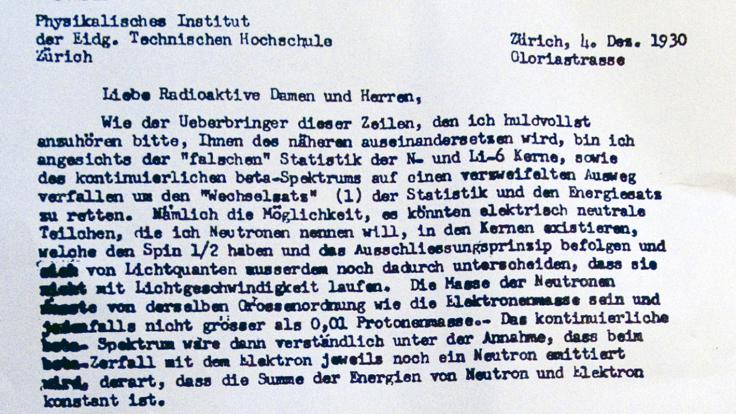

“I thought, let me try one crazy thing,” López recalls, “and I wrote to my former University of Massachusetts advisor, Michael Kreisler, to ask if there was any way to do HEP research from Puerto Rico.”

Kreisler suggested López write to Leon Lederman, then the director of Fermilab, who offered López a summer job. López spent the next five years analyzing experimental data and building a new experiment called E687 that would explore physics related to charm particles, under the guidance of physicist Joel Butler.

Taking inspiration from the collaboration back home to the island, López applied for a competitive DOE grant and later an EPSCoR grant, designed to help US institutions conduct research while building capabilities to become more competitive for other federal funding. López and UPR Mayagüez won those grants. The limited-term EPSCoR grant helped to develop capabilities, which resulted in the competitive grant being continually renewed for 20 years with increasing amounts of funding to support an increasing number of student researchers as well as a postdoc and two other faculty members.

By the time he retired in 2013, López had taught physics to thousands. Twenty-five of his students went on to finish master’s degrees in high-energy physics—five from Puerto Rico and many others from Latin American countries such as Mexico, Peru and Colombia. At least six continued to earn PhDs.

A student’s journey

Former UPR student Carlos Andrés Flórez Bustos, now associate professor of physics at the University of Los Andes in Colombia, attributes much of his success to meeting López and the international research opportunities his program offered.

By the time Flórez was 15, he had read Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes three times. But he never dreamed he would later teach at one of the leading universities in Latin America, which happens to be in his hometown of Bogotá.

“I come from a poor family and didn’t even have money for the college application form,” he says.

He did well on the national standardized test in physics and math, so a friend advised him to apply to a public university, and with the help of a second friend they pulled together the registration fees.

“The experience at UPR changed my life,” he says. “Mainly because I met professor Angel López, to whom I owe so much.”

López sent him to Cornell University for high-energy physics research one summer, then to Fermilab for his master’s thesis project on the CMS experiment. While at Fermilab, he met a professor from Vanderbilt University, where he eventually completed his PhD.

López takes pride in his students and their accomplishments, and knowing what a difference their college experience made in their lives. “Many students came to the physics program without knowing a word of English or much of the world outside the small area of the country they came from,” he says. “Then they go on to work on some of the biggest physics experiments in the world.”

Small programs with big futures

Despite the economic challenges in Puerto Rico, which were exacerbated by Hurricane Maria in 2017, the physics program at UPR Mayagüez is going strong, according to López’s successor professor, Sudhir Malik. Malik secured funding from the National Science Foundation to continue high-energy physics research on the CMS experiment. The campus also continues to host a local grid-computing cluster, and other Physics Department colleagues are collaborating with Fermilab on neutrino experiments, he says.

Malik supports two software projects, FIRST-HEP (The Framework for Integrated Research Software Training in High Energy Physics) and IRIS-HEP, a software institute aimed at developing the cyberinfrastructure required for the challenges of data-intensive research expected in the 2020s, for instance, at CERN’s future High-Luminosity Large Hadron Collider.

He also aspires to make an even broader impact on the local community by expanding collaborations with high school teachers in strengthening STEM teaching and learning in Puerto Rico. Key to preparing young scientists for the research of today and tomorrow, he says, is exposure to the large, international, collaboration-based experiments that are characteristic of the field.

With 50 countries involved in one experiment, the focus becomes whatever connects the people involved: “You sit in a very diverse group and must listen,” he says. “Coming from India myself, I think we need to work very hard on this aspect. You forget your differences when the goal is common.”

Although the program at the University of Colima is much younger, Aranda and his colleagues are optimistic about its potential impact. Saenz says they will see their students land permanent positions in academia in the next five years, and only time will tell if some of those will be back in Mexico. Because their requirements are stringent, only about 40% of physics and math students at Colima continue after the first year, but the remaining students find new worlds of opportunity.

Mayra Cervantes, who graduated from the University of Colima in 2007 and went on to get her PhD at Purdue, finds herself applying much of what she learned in particle physics to her current industry job in the energy sector.

“I had a great experience in Colima,” she says. “The professors are really interested in making sure all the students succeed, not just the top percent. They use their connections around the world to create opportunities.”

After graduating from Colima, Cervantes went to Italy to take advanced courses in high-energy physics and work on the ATLAS experiment. When she returned to Mexico, she worked on the HAWC experiment before starting her PhD program, during which she returned to Italy to collaborate on the XENON dark matter experiment. Along the way she met several students whose goal was to go into industry using similar techniques to solve exciting problems, which inspired her to do the same.

For Cervantes, the world of scientific research has a particular beauty, which can be applied to many other areas of life: “Physicists go deeply into the problems and approach them in many different ways.”

That world is opening up for more students, thanks to scientists like Aranda, López and their colleagues. With a little more luck and a lot of hard work, their efforts could bring the students they teach a more certain future.