A city steeped in fantasy is born in the Nevada desert at this time each year as a makeshift community descends on an ancient lakebed, briefly transforming it into a seemingly chaotic assemblage of costumed cars, embellished bicycles, giant-scale art and other remarkable contraptions built to defy convention and the rigors of the environment.

At the annual, weeklong Burning Man event, which began this week, thrill-seeking residents and makeshift masterpieces endure sudden thunderstorms and dust storms, huge wind gusts and 50-degree temperature swings.

The event draws more than 50,000 participants each year, elevating it briefly to the status of the sixth most populous community in Nevada and one of the top 500 most populous urban areas in the United States.

Every year, physicists are among its citizens.

Debbie Bard, a SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory cosmologist who plans to attend this year's event, says it is a departure from the high-tech world of science that occupies her work life, though there are some obvious parallels to her scientific endeavors.

“The logical way we've been trained to think through a problem is really useful, especially in high-pressure situations, such as if your camp is about to blow away in 70 mph winds," she says.

Bard has in previous years worked with SLAC scientist Eric Charles and other collaborators on an art vehicle called the "Dodobus"—a school bus (shown above) modified to look like a sailing vessel—that makes regular voyages to Burning Man.

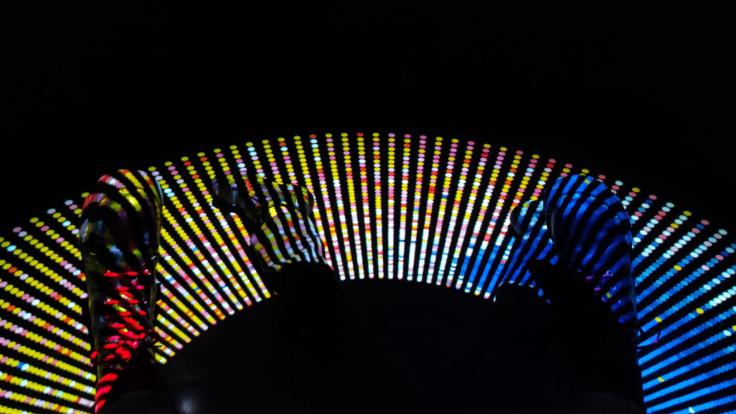

Bard has also tapped her scientific expertise for a thematic camp at Burning Man. "A few years ago we had a lighting-effects theme camp," she says. "We used strobes, monochromatic lights, lenses and mirrors to create some really cool effects and experiences."

For Charles, who works in the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope Instrument Science Operations Center at SLAC, Burning Man "is just something I do for fun," though he has mixed work with pleasure by driving the Dodobus to the 4th International Fermi Symposium, a scientific conference held late last year in northern California. It was a big hit, he says. "Lots of colleagues were hanging out on the bus every evening."

Charles first attended Burning Man in 1998 and has been about 10 times, including this year. "A lot of work goes into organizing whatever project you are doing for Burning Man,” he says. “Depending on the number of people involved, it can take some thought to get them to work together as well as possible"—much like an international particle physics project.

“The people skills we develop as scientists come in handy,” Bard agrees. “Everyone pitches in to help because everyone is committed to the success of the project.”