Liz Lerman is an accomplished choreographer, writer, performer, educator, and artist whose laurels include the American Choreographer Award, an honorary doctorate from Williams College, Washingtonian Magazine's 1988 Washingtonian of the Year and a 2002 MacArthur “Genius Grant” Fellowship.

She founded The Liz Lerman Dance Exchange, based in Takoma Park, Maryland, in 1976. Since 2006, the group has traveled throughout the country performing a multimedia dance production titled Ferocious Beauty: Genome. With Gregor Mendel as a leading character, this work examines the nature of discovery and the implications of present-day research in genetics.

Now, Lerman and her company are producing a piece that explores the question of how things begin, and are advancing their research through conversations with specialists in a variety of fields, including scientists at the Large Hadron Collider.

On her second trip to CERN, the European particle physics lab near Geneva that is home to the LHC, Lerman brought with her a small team of dancers who spoke with scientists and even performed a few dances in the LHC tunnels and work spaces. Lerman spoke with Symmetry’s Calla Cofield about her impressions of CERN’s huge scientific community, whether symmetry is beautiful, and why dancers and physicists share a certain kinship. She remains in contact with a number of scientists as she begins to shape the piece, set to debut in the fall of 2010, that she tentatively calls Matter of Origins.

What made you choose particle physics and the LHC for your next project?

Well, that completely took me by surprise. I wasn’t looking, and I wasn’t imagining it at all. I was approached by Gordy Kane, a physicist at the University of Michigan and director of the Michigan Center for Theoretical Physics, to at least think about [going to CERN] and I decided to go take a look. Once we went, then a whole lot of things took over.

A long time ago, my dance company spent almost two years going back and forth to a shipyard—the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard—for a big community arts project with multiple outcomes, including a finalé of 700 participants.

And in some ways CERN reminded me of that: this huge complex, this enormous number of people working together toward something much bigger than themselves. It’s a very inviting kind of environment just to see the thousands of stories that are there.

I think the other thing is, as a dancer and choreographer I’ve spent a tremendous amount of my life defending something that’s very hard to see. I mean people see dance, they see the dancers, but they have trouble understanding why it’s valuable, what you’re trying to say. And in some ways I feel that’s reflected in what I learned initially from the physicists. It’s very abstract, it’s hard to see, people have trouble trying to understand it, it has tremendous value to us as a civilization but it's not easy to explain. So I think I felt a certain kindred spirit even though our fields are obviously quite distinct.

What was the response from the physicists at CERN when you talked to them about your project?

I think people like to talk to artists, and the scientists are mostly very happy to speak. A lot of times they tell us things that they think we want to hear. They tell us things that they think are physical, or things that they think would look beautiful as a dance. But sometimes they’ll just look at you with great bemusement and say, “Well, what’s on your mind? What do you want to know?”

But what was really fun at CERN was that the minute Ben Wegman, the dancer, was down in the ATLAS cavern and he was dancing, just spinning, work stopped. People started flashing their camera phones and we understood later that there had been an electric current through the whole place. Word spread that there was a dancer down in the cavern. I think people got really excited. And of course they laughed and hooted and all that, but we’re used to that. That was very interesting.

The other thing that I love—and maybe this is why it’s interesting for scientists to spend time with us—is when you have to explain yourself to somebody who doesn’t know any of your jargon, you are forced to try again. And when you try again, then I think sometimes you stumble into a way of describing, modeling, or actually understanding yourself better. I know that’s true for me when I try to explain myself to people who don’t know what I’m doing. I think that happens for the scientists too. And you know, we ask very challenging questions because we have a way of thinking and seeing that’s different.

As a dancer and choreographer I’ve spent a tremendous amount of my life defending something that’s very hard to see.

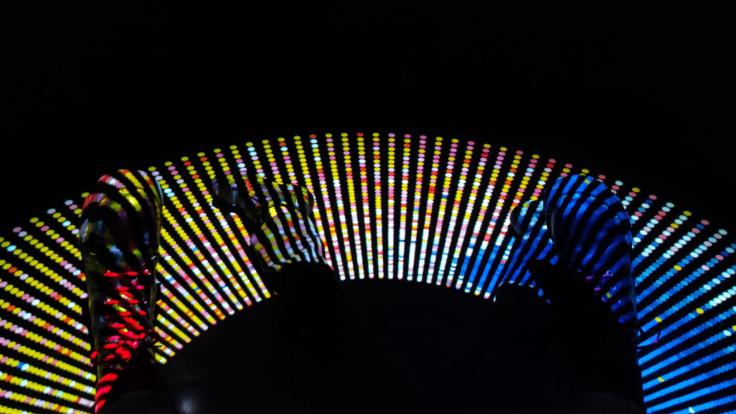

Members of the Liz Lerman Dance Exchange in Ferocious Beauty: Genome, a science-based, multimedia performance piece.

What were the challenging questions?

I’ll tell you a conversation I’m in the midst of with Gordy. I keep hearing about symmetry. I read things by the physicists and they talk about symmetry and supersymmetry and the elegance, simplicity, beauty, and aesthetics of symmetry. Well, I wrote Gordy and I said for me this is a problem, because for me symmetry is not beautiful: symmetry suggests amateurs, symmetry suggests static. So now we're in a big discussion about that.

Meanwhile, with that conversation in mind, I went to Spain, where my daughter is spending her junior year, and we went into Cordoba. And we saw this Islamic influence in the architecture there and in these tiles that are all symmetric. And I got interested because I’m in the middle of this debate with Gordy and I actually liked the symmetry I saw there. I picked up a book on Islamic art and symmetry and the author says the Islamic symmetric design is an expression of the “essential relationships that lie beneath the visual surface of the world.” So I am delighted to go down that path for a while, to study these ideas and to see where they go and to compare the language to what I’m hearing from the physicists. Whether this shows up in the piece or not I don’t know, but we are working hard on symmetry right now.

Were there any other big ideas that stood out to you when you talked to these scientists?

One of the things we’re interested in is what are the questions they’re asking, and which of those questions have real, enormous resonance for the public? For example, they think they’re going to understand more about the Big Bang, and I think the public is just incredibly interested in that. I think how we see our beginnings really affects us emotionally, intellectually, spiritually, in all kinds of ways.

Last time I saw Gordy I said, “What happens if you don’t find [the Higgs boson]?” He’s convinced they're going to find it, and I said what if you don’t? Who’s right, who’s wrong, and do you have to put some ideas to bed then? And does that mean that people who spent 20 years looking for it feel regret or shame, or is this the end of an idea? I don't know if regret is part of a scientist’s world. In science, what happens when things turn a corner?

One of the conversations we got into a lot, for some reason, was physicists’ spiritual feelings. They kept bringing this up. It was so interesting. I didn’t ask a question about that but it just kept coming up, what the state of their belief was. And in fact I told them an old story, a Jewish creation story that’s not the biblical one you usually hear; it’s from the Midrash, one of the Jewish alternative stories to the Bible. God wants to create the world but God can’t because God takes up too much room, so God contracts in order to make room for the world. That’s a shorthand version. And the physicists just loved that.

Experimental physicist Maria Spiropulu, left, illustrates ideas for Liz Lerman over brunch in Geneva.

What did people have to say about spirituality?

There was a wide range, from cynicism to complete spiritual belief to people who actually said straight out, “My science is my religion, but let me point out all the parallels.” And then they would point out all the ways in which CERN was like a church, and who was playing what role.

I think I did ask them if they were looking at the Big Bang, how they were helping the public through questions. You know, did they feel any responsibility about people who come with their religious beliefs about that? And in fact the scientists are thinking about it. They don’t dismiss that question. I find that most professionals feel a responsibility to the issues that their field has to address or is causing them to address. But most of our professions don’t value our helping make that work for the public. It’s as if you're more of a professional if you stay disengaged from the public’s need. And I find that very peculiar, but I find that’s true across the board. I’d love to see that change.

In some of the early dancing that your group has done for this project, you have people representing particles. What does that do to our notion of a particle?

It’s one of those interesting things where we realize that all language is symbolic. Because even calling it a particle, you might think of a dust particle or a dirt particle or whatever is in people’s imaginations. I ran into this with genomics stuff. They talked so much about protein folding, and we got so into folding and had such a good time with all this folding stuff. And then I finally saw an animation of what people thought protein folding was, and it’s not folding at all! It’s more like intense wrapping. I would never call it folding. That’s when I realized that our language is problematic, too. It’s not just that dancing is an approximation, but the language is an approximation unless you can see the actual thing, and with a lot of this stuff you can’t. And that got me very excited, actually. I thought for a while that I could make a dance about dueling metaphors, because people say such different things when they’re trying to explain something that you can’t see.

For me, symmetry is not beautiful: symmetry suggests amateurs, symmetry suggests static.

Ben Wegman moves down an aisle of server racks at CERN’s Computer Center.

What else would you like to see happen at CERN in terms of artists going there?

I wish there was enough money for CERN to have a whole group of artists there, because there are so many good stories to be told. It just wouldn’t even cost that much to have an official storyteller in residence. My husband is a storyteller; that’s his job. He collects stories and he tells people stories and he went with me on both these trips [to CERN], and unlike my work, which requires lots of bodies and lots of tech, he just pulls a stool out, sits down, and starts talking.

The thing is, there’s so much to be learned. Everybody working at CERN has an interesting story. Even if you just started with “Why are you here?” or “How did you get here?” or “Who’s the person in your life who helped you understand that this is where you needed to be?” we would learn so much about teachers! We would learn probably all there is to know about good teachers if we asked everybody at CERN who’s the one that inspired you, when did it happen, why. And imagine the catalog of incredible discoveries we would hear. Or, we saw this guy mowing the lawn while we were there, and we thought wouldn’t it be interesting to interview the guy who mows the lawn? What do you suppose he’s thinking? You think he’s worried? (laughs) You think he wonders if, you know...

Does he wonder if they’re going to create a black hole?

You know, he may embody some of those things we keep hearing about, I don’t know.

Are you going back to CERN again?

I hope to. I want to very, very much. We hope to have a three-week residency. But right now the funding in our world is really hard hit. We need to do it, but I don’t know if we’ll get to.

The performance is set to premier in the fall of 2010. Will you perform it at CERN?

We would love to take it to CERN, and we talked to a festival held about ten to 15 minutes away from CERN where we could perform it. Or we could take it apart and do pieces of it around CERN. But we’d love to perform there.