On March 10, 2018, the underground cavern that holds CERN’s CMS experiment had some rare visitors: fashion models, posing in dresses that seemed part sculpture, part science fiction. It was a photo shoot for the fantastical Magnetic Motion collection, created by famous Dutch fashion artist Iris van Herpen, inspired by the laboratory’s equally fantastical machinery.

Back in her atelier in a sun-filled warehouse loft in Amsterdam, Van Herpen, 34, stands tall with long red hair before a crowd of mannequins outfitted in black, white and midnight blue garments that seem constructed of industrial materials. At a table, eight young co-workers—mostly with a design background, van Herpen says—are shaping fabrics into forms that resemble the wings of butterflies. About 30 pairs of scissors of different shapes and sizes hang on the wall.

Van Herpen, who lives in Amsterdam and Paris, started her own label in 2007 after graduating from the Artez Institute of the Arts in Arnhem, The Netherlands. She creates two womenswear collections a year and regularly participates in exhibitions. Anyone who has seen these exhibitions will be unsurprised to learn she follows new developments in science.

“My interest in CERN goes back a long time,” van Herpen says. “I was fascinated by discoveries like the Higgs particle, and I often checked the website for news. CERN appeared to be a magic place.”

In 2014 Ariane Koek, founding director of CERN's Arts@CERN artist-in-residence program, invited van Herpen to visit the European research center.

At CERN, van Herpen and Philip Beesley, a Canadian architect with whom she often collaborates, voyaged underground to tour the detectors of Large Hadron Collider. “We met with physicists who explained in easy language about the collisions of particles, the transitions between matter and antimatter, and how the magnets and devices are linked together,” she says.

One of those physicists was CMS Technical Coordinator Austin Ball.

“She was very interested in which countries are involved in CERN, how it is run, the gender balance and also what drove the shape and choice of the color scheme of the experiment,” he says. “She asked many questions about our materials.”

Van Herpen says she was struck by the beauty of the ATLAS and CMS detectors.

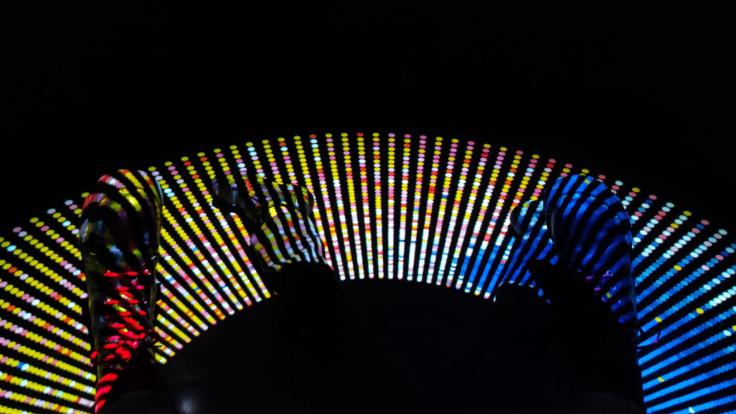

“It appeared to be couture, a stitched tapestry of colored wires, magnets and devices, and all applied by hand. Craftsmanship and the power of human collaboration were incredibly tangible.”

Eye to eye with the experiments, van Herpen did not instantly have visions of the pieces she would create, she says. The main idea she brought home was that CERN is trying to lure, control and understand the invisible forces of nature via technology and human intellect—a familiar task.

Letting nature decide

Van Herpen does some science and engineering of her own. When she creates a new collection, she uses technology to develop new techniques and new materials.

It’s a time-consuming, collaborative process, she says. “Sometimes we are not able to realize what we intend to. There is analogy with scientific experiments, as a process of trial and error. Only when the desired materials are ready the actual design process starts.”

Van Herpen says she starts with the idea of a silhouette in her head. Using a mannequin or sometimes a model, she drapes the material with her hands. “You could compare it with molding,” she says.

The time to drape one piece varies from a few hours to three days. “Every single piece is draped by me,” she says, “because cutting expensive materials that took months to develop is scary.”

For the Magnetic Motion collection, van Herpen and Beesley worked with magnet artist Jólan van der Wiel. They did things like adding metal powder to silicon, then placing magnets above and below to shape it into spiky forms.

“We had no control over the outcome, which was thrilling,” she says.

In the end, the collection consists of 25 pieces. Some are made with micro-webs of lace veil. Others contain luminescent crystal forms. In still others, sharp, highly reflective feathers punctuate soft shapes.

“The shoes, belts, necklaces and clutches were ‘grown’ by using magnetic fields,” van Herpen explains.

Van Herpen has a favorite piece in the Magnetic Motion collection, she says. Opening a book of photos, she points to the ‘crystal dress,’ which appears to be made of ice.

She had previously experimented with different ways to create the illusion of a liquid dress, frozen mid-splash, via a variety of techniques, including 3-D printing. The idea inspired her 2011 collection, Crystallization. TIME Magazine named her 3-D printed dress design one of the 50 best inventions that year.

She had attempted to 3-D print an especially challenging version of the dress using transparent, organic polymers. The company she contacted said that the design was too fragile; they could not do it.

Her visit to CERN inspired her to try again. “Always push the boundaries,” she says. This time, “it was a special moment when it worked.”

Living in an immaterial world

In 2018, another dream came true: CERN granted van Herpen the rare permission to do a two-day photo shoot of Magnetic Motion at the laboratory.

In a moment when the LHC was not in use, one truck loaded with the pieces took off from Amsterdam to Geneva, and another carried the equipment of fashion photographer Nick Knight from London.

All of this led to the moment van Herpen, Knight and a small group of models gathered in front of the CMS detector along with Ball, who was there to deal with technical and safety concerns.

"Of course the models had to wear safety helmets,” van Herpen says. “We brought transparent ones.”

Ball said he had never seen anything like it. “Without exception all pieces were very ingenious, spectacular, mostly different from anything I expected—and also very difficult to fabricate.”

Van Herpen says she is grateful for the unique opportunity.

“It was a beautiful gathering of two worlds,” she says. “I have experienced a tip of the iceberg of CERN and believe that I can get even more out of it. Hopefully I will get the chance to return.”