If attendees at the welcome reception for CERN’s first artist-in-residence learned one thing last night, it was that Julius von Bismarck is not afraid to disrupt others with his art.

In a way, this trait puts him right at home with CERN scientists: the kind of people who always question, the kind of people who fill an auditorium to discuss the possibility that a long-held law of physics could be broken.

But von Bismarck is not a CERN scientist. So inviting him into the laboratory, where he will stay for the next two months, is a sign of trust – not that he won’t disrupt the scientists, but that, if he does, the experience could be worthwhile.

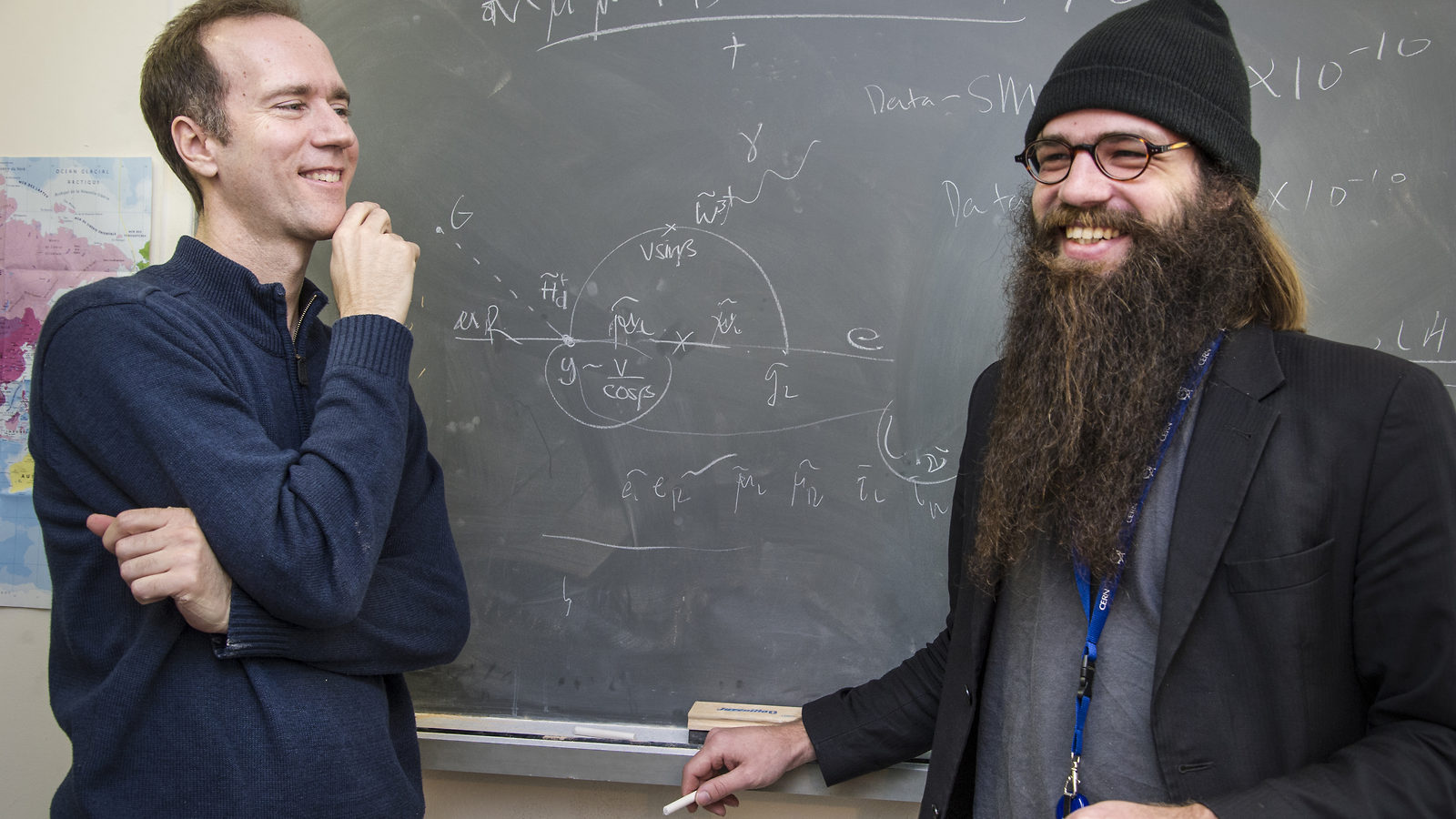

As the winner of the Collide@CERN prize, the artist will spend time at CERN with physicist James Wells, his chosen inspiration partner, and then will spend a month working with digital media mavens at the organization Ars Electronica. He will present a work based on his experiences at the laboratory in September.

Von Bismarck, 28, has used invention, experiment and, in many cases, the participation of an unsuspecting crowd to address questions about how we interact with the world around us.

In 2006, he created a white, spherical helmet that blocks the wearer’s view of anything but a live video feed from a camera attached to a balloon overhead. “It totally changes your perception,” von Bismarck said.

At last night’s reception, he showed a video of himself walking through Berlin’s central train station wearing the contraption. “After a while you get used to it,” he said. “What never goes away is the shakiness. The world is losing stability.”

The video cut between his out-of-body perspective of himself and the perspective of a cameraman filming from several feet away. Audience members laughed as the helmeted artist awkwardly tried to shake hands with a curious passer-by. They skipped a breath as he shuffled dangerously close to the tracks.

In a later project, von Bismarck interacted with the public in a different, more subversive way. He invented a device that projects a bright image for a split second when it detects the light from a camera flash. That way, “I’m able to smuggle information into pictures of others,” he said. “Your eyes are not fast enough or your brain is not fast enough to see what it is. Only in your picture will you see something different.”

During President Barack Obama’s first public speech in Europe, von Bismarck projected a hidden white cross onto the president’s podium. The act made a statement not only about the trustworthiness of photography but also about public perception of the event itself.

Von Bismarck has embedded himself with professional photographers at public events, spending hours pretending to be one of them as they waited to take the shots he would alter. “It was fun to be there not as a photographer – but as the opposite,” he said.

Von Bismarck is embedded once again. But during his months at CERN, he won’t be able to play the chameleon. Media attention aside, the artist can’t help but stand out as he walks through the cafeteria, tall with tidy, shoulder-length hair and a long, wooly beard. Pleased and maybe just a little uncomfortable, he surveys the scientists all around him.

“This is a unique chance for me,” von Bismarck said at the reception. “It’s very far away from my normal life. I’m already thinking totally different.”