For many government officials, groundbreaking ceremonies are probably old hat—or old hardhat. But how many can say they’ve been to a groundbreaking that’s nearly a mile underground?

A group of dignitaries, including a governor and four members of Congress, now have those bragging rights. On July 21, they joined scientists and engineers 4850 feet beneath the surface at the Sanford Underground Research Facility to break ground on the Long-Baseline Neutrino Facility (LBNF).

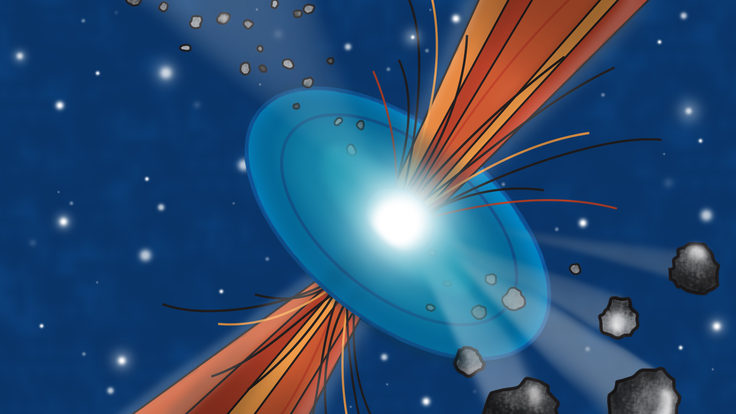

LBNF will house massive, four-story-high detectors for the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE) to learn more about neutrinos—invisible, almost massless particles that may hold the key to how the universe works and why matter exists. Fourteen shovels full of dirt marked the beginning of construction for a project that could be, well, groundbreaking.

The Sanford Underground Research Facility in Lead, South Dakota resides in what was once the deepest gold mine in North America, which has been repurposed as a place for discovery of a different kind.

“A hundred years ago, we mined gold out of this hole in the ground. Now we’re going to mine knowledge,” said US Representative Kristi Noem of South Dakota in an address at the groundbreaking.

Transforming an old mine into a lab is more than just a creative way to reuse space. On the surface, cosmic rays from the sun constantly bombard us, causing cosmic noise in the sensitive detectors scientists use to look for rare particle interactions. But underground, shielded by nearly a mile of rock, there’s cosmic quiet. Cosmic rays are rare, making it easier for scientists to see what’s going on in their detectors without being clouded by interference.

Going down?

It may be easier to analyze data collected underground, but entering the subterranean science facility can be a chore. Nearly 60 people took a trip underground to the groundbreaking site, requiring some careful elevator choreography.

Before venturing into the deep below, reporters and representatives alike donned safety glasses, hardhats and wearable flashlights. They received two brass tags engraved with their names—one to keep and another to hang on a corkboard—a process called “brassing in.” This helps keep track of who’s underground in case of emergency.

The first group piled into the open-top elevator, known as a cage, to begin the descent. As the cage glides through a mile of mountain, it’s easy to imagine what it must have been like to be a miner back when Sanford Lab was the Homestake Mine. What’s waiting below may have changed, but the method of getting there hasn’t: The winch lowering the cage at 500-feet-a-minute is 80 years old and still works perfectly.

The ride to the 4850-level takes about 10 minutes in the cramped cage—it fits 35, but even with 20 people it feels tight. Water drips in through the ceiling as the open elevator chugs along, occasionally passing open mouths in the rock face of drifts once mined for gold.

“When you go underground, you start to think ‘It has never rained in here. And there’s never been daylight,’” says Tim Meyer, Chief Operating Officer of Fermilab, who attended the groundbreaking. “When you start thinking about being a mile below the surface, it just seems weird, like you’re walking through a piece of Swiss cheese.”

Where the cage stops at the 4850-level would be the destination of most elevator occupants on a normal day, since the shaft ends near the entrance of clean research areas housing Sanford Lab experiments. But for the contingent traveling to the future site of LBNF/DUNE on the other end of the mine, the journey continued, this time in an open-car train. It’s almost like a theme-park ride as the motor (as it’s usually called by Sanford staff) clips along through a tunnel, but fortunately, no drops or loop-the-loops are involved.

“The same rails now used to transport visitors and scientists were once used by the Homestake miners to remove gold from the underground facility,” says Jim Siegrist, Associate Director of High Energy Physics at the Department of Energy. “During the ride, rock bolts and protective screens attached to the walls were visible by the light of the headlamp mounted on our hardhats.”

After a 15-minute ride, the motor reached its destination and it was business as usual for a groundbreaking ceremony: speeches, shovels and smiling for photos. A fresh coat of white paint (more than 100 gallons worth) covered the wall behind the officials, creating a scene that almost could have been on the surface.

“Celebrating the moment nearly a mile underground brought home the enormity of the task and the dedication required for such precise experiments,” says South Dakota Governor Dennis Daugaard. “I know construction will take some time, but it will be well worth the wait for the Sanford Underground Research Facility to play such a vital role in one of the most significant physics experiments of our time."

What’s the big deal?

The process to reach the groundbreaking site is much more arduous than reaching most symbolic ceremonies, so what would possess two senators, two representatives, a White House representative, a governor and delegates from three international science institutions (to mention a few of the VIPs) to make the trip? Only the beginning of something huge—literally.

“This milestone represents the start of construction of the largest mega-science project in the United States,” said Mike Headley, executive director of Sanford Lab.

The 14 shovelers at the groundbreaking made the first tiny dent in the excavation site for LBNF, which will require the extraction of more than 870,000 tons of rock to create huge caverns for the DUNE detectors. These detectors will catch neutrinos sent 800 miles through the earth from Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in the hopes that they will tell us something more about these strange particles and the universe we live in.

“We have the opportunity to see truly world-changing discovery,” said US Representative Randy Hultgren of Illinois. “This is unique—this is the picture of incredible discovery and experimentation going into the future.”